In this third part of the interview, Ramdhari Singh Diwakar shares with Arun Narayan his impressions of Renu, Nagarjun, Madhukar Singh and Chandrakishore Jaiswal. In the concluding part, we will find out about how he writes and how he relates to his readers:

Could you share your memories of Phanishwarnath Renu?

When I was pursuing my matriculation (1954-55), Renu’s Maila Aanchal was already well known. Vasudev Mandal, one of my teachers and a Hindi scholar, gave the book to me to read. It was published by Samta Prakashan. It had a green cover and rather loose binding. Sumitranandan Pant’s poem Bharat Mata Gramvasini was printed on the back cover of the book. I was in Standard 9 then – there was no way I could have read that thick a novel. I just flipped through it. I saw Renu for the first time at Forbesganj when I was in college. At the time, he had short hair. He started keeping long hair after meeting Pant. I remember a lot of things about Renu. I spent time in his company. My reminiscences about Renu have been published in many magazines. Banas Jan has a long memoir dedicated to him. There is no need to repeat them. But I would say that I would not have been a writer but for Renu.

Renu had told me that when he read my story Tuladand, he had mistaken me for Ramdhari Singh Dinkar. “Since when has Dinkar started writing stories? He hasn’t written a single story till now,” Renu thought.

Initially, I was under Renu’s spell. But later I carved out a separate path for myself. I felt that Renu had written for his times and I have to write for mine. Renu was not relevant for my times. So, I chose a new path, which was different from his. I would insist that unlike Renu, I am not an “aanchalik” (regional) writer. My short stories and novels also unfold in the same region in which Renu’s writings did. But my stories and novels are not about a region. India is changing, villages are changing. Renu’s villages no longer exist. So, while being a great admirer of Renu, I am not a writer in his mould.

Anything more you would like to share about Renu?

I will share two reminiscences. Renu also shared my reminiscences with others. He had himself admitted to me. My story Tuladand was published in Dharmyug in 1973. One of Renu’s stories, probably Aginkhor, was published in the previous issue. At that time, getting published in Dharmyug was considered an achievement. As I mentioned earlier, he read my name as Ramdhari Singh Dinkar and was surprised that Dinkar has started writing stories. His house in Rajendra Nagar was close to Dinkar’s Udyachal. He immediately set off for Dinkar’s home with a copy of Dharmyug. On the way, he flipped through the magazine. On the second page of the story, my name, picture and a brief introduction was published. It was then that he realized that the author was not Ramdhari Singh Dinkar but Ramdhari Singh Diwakar. He also remembered that I was the same person who used to meet him at Forbesganj and Orahi Hingna. Though the confusion was cleared, he continued on to Dinkar’s home and told him about me. He told Dinkar about the confusion. Dinkar also recalled that the boy, whose name matched his, had read his poem at the convention of Hindi Sahitya Sammelan in Forbesganj. “But he used to write poetry,” Dinkar said. Renu replied, “He did but he has now started writing stories.” Renu himself had told me all this.

Also read: Ramdhari Singh Diwakar: ‘It took Rajendra Yadav only 13 days to publish my short story’ (Part II)

Anything else about Renu which you haven’t shared till now?

I was rather close to Renu. But I will not talk much about him. There are many writers and poets who have much more to say about Renu. Around 1974, Renu was quite active in JP’s Sampoorna Kranti Movement. In this connection, he had visited my village Narpatganj. I met him. He also visited my home. Many others were also present there. My brother, Ramkripal, has some interest in literature. He asked Renu, “Do you consider Gulshan Nanda a writer?” Renu said, “Yes, I do.” “Why?” my brother asked. Renu replied, “If I do not consider him a writer, he will not consider me a writer. He is a big name. His novels sell lakhs of copies. His novels have been adapted for films.” Renu also referred to a national literary gathering in Delhi. Gulshan Nanda was also invited. He was seated in the first row. Renu, Jainendra Kumar and others were in the second row. The people from the film industry knew Gulshan Nanda. They didn’t know Renu. A leading film director was surprised when he was told that Dharamvir Bharati, the editor of Dharmyug, was also a writer.

What have you to say about Nagarjun?

The leftists have placed Nagarjun on such a high pedestal that saying anything against him is inviting trouble. Everyone knows how Nagarjun turned Buddhist from a pure Brahmin. He used to travel throughout the country. He would stay at the homes of budding writers for weeks and months. His hosts would consider themselves honoured and lucky that Baba had blessed their homes. Some years ago there was a controversy when a woman levelled serious allegations against him.

At a seminar, when I asked Nagarjun about the regional flavour in Renu’s writings he replied in Maithili, “When ‘heeng’ [asafoetida] is added to ‘arhar’ [pigeon pea] dal, it adds to the taste. But what if you make a sherbet of ‘heeng’? Renu has done just that.”

Baba was known as Nagarjun in Hindi and as Vaidyanath Mishra Yatri in Maithili. I was well acquainted with him. When he was living in Darbhanga, he visited my home twice. He had a great affection for me. I am yet to meet a writer as simple and as unassuming as him. He was a real poet. But I think he was not as great as Kedarnath Agarwal, Shamsher and Muktibodh. He lacked integrity. One never knew when he would change track. He was someone in his mother tongue Maithili, someone else in Hindi, and still someone else in his personal life. He lived in Darbhanga for 8-10 years in the last phase of his life. I got to know him closely during that period. Renu and Nagarjun were friends. Renu treated him like his elder brother. But I think Nagarjun had a strange complex about Renu. Maila Aanchal had made Renu famous. He became well-known not only in the Indian literary world but also internationally. Renu’s popularity made Nagarjun bitter. His comment about Renu’s writings being “heeng ka sherbet” saddened me. It exposed his bitterness towards Renu. There are many more things. But I would not like to talk about them now.

How do you view Rajkamal Chaudhary?

Rajkamal Chaudhary had moved to Patna after staying for years in Calcutta. There was a writer called Narendra Ghayal in Patna. He used to bring about a magazine titled Patjhad. This was 1969-70. Patjhad used to carry Renu’s memoirs. I remember that Renu had written that in 1953-54, when Maila Aanchal was being printed at Patna’s Samta Press, Rajkamal used to visit the press everyday to read portions of the novel. At that time, Rajkamal was not well known.

After Rajkamal’s death, I published my first poem in Aryavarta titled “Rajkamal Chaudhary Ke Prati”. By that time, I had read his novel Macchli Mari Huyi and his poems. Rajkamal was a poet and a writer of short stories who destroyed moral values. New poets and writers accorded him a high status but he was a misfit in the Indian value system. I have also read his Maithili stories. In Maithili he felt more natural and emerged as a writer with a wide canvas. But that is not the case with his Hindi writings. There, he seems to be flaunting his modernism. Had his Hindi writings been as natural as those in Maithili, he would have been a better writer.

Your take on Madhukar Gangadhar?

Madhukar Gangadhar was Renu’s contemporary and both were very close. Both were from Purnea and they worked together at Akashwani, Patna. But Madhukar Gangadhar was filled with a strange kind of arrogance. He addressed Renu as “Bhaiya” and conversed with him in the local dialect. Renu’s fame and Maila Aanchal’s popularity had generated some sort of resentment, frustration in him. He was a talented writer. I have read many of his short stories and novels. I was quite close to him. He even arranged a job for me at Patna Akashwani. But, by that time, I had been appointed as a lecturer.

He spent his entire creative energy on criticizing Renu. He branded Maila Aanchal as a carbon copy of Dhodhaya Charit Manas. Once I told Renu about him. I asked him, “Gangadhar doesn’t stop criticizing you. Why don’t you respond?” Renu’s answer was a big lesson for me. He said, “Diwakar ji, if I start responding to my critics, all my creative energy will be spent on it. Many critics have dragged me through the mud over Maila Aanchal. So, Diwakar ji, the best thing is to continue with your work and not respond to your critics.” I have been trying my best to follow his advice.

Madhukar Gangadhar had two wives. His first wife lived in his village and the second, a Bengali, lived in Patna with him. He had virtually abandoned his children from his first wife. My novel Panchami Tatpurush is based on Gangadhar’s abandoned wife. It opens with these lines: “Ahilya testified before the court – ‘Yes, she is my daughter, born from my womb.’” Thus, Gangadhar’s life was very complicated. He came from a big family. Laxmi Narayan Sudhanshu was his relative. Dhamdaha was a citadel of feudal lords. Gangadhar was its product.

What are your views on Madhukar Singh? How do you rate his writings?

Madhukar Singh had no match. We became closer after he moved to Patna. Once I asked him about his family background. He replied, “Diwakar ji, I am a labourer’s son.” He stressed on the word “labourer”. He was very simple and affable. He didn’t care much for aesthetics. He wrote about what we underwent. He was not a pretender. His works may lack aesthetics but they are imbued with the realities of life and an ardent desire to change the world. In a nutshell, among Hindi fiction writers, he was the god of fire.

He had his ear close to the ground. He was driven by a desire to transform the world. He was not merely a leftist. He belonged to the extreme left. He had a deep understanding of the psyche of the common man. He lived in a village and wrote about villages. Renu also came from a village but there was a great difference between the two. All said and done, Renu had some degree of elitism about him. But Madhukar Singh was a simple, rustic writer. This is the difference between sons of soil and others.

None of the short stories or novels of Madhukar Singh belong to the “Shant Rasa”. They are blizzards of unrest. I think two factors came in the way of him gaining eminence – one, his OBC background, about which he has written in his reminiscences about Kashinath, and two, his leftist ideology. Both these factors are big impediments in gaining prominence in Hindi literature. Renu faced none of the two. Madhukar Singh had a deep knowledge of folk tales and folk songs but he had revolutionary leanings. He often used to relate a folk tale to me. It was about Ram playing Khajari. It was like the tale of Hirna-Hirni. It was a symbolic tale. Its basic message was how king Ram’s heartlessness and cruelty led to violence against the common man. Madhukar Singh would become very emotional while singing this Bhojpuri song. He was very compassionate, simple and loving. I can’t forget him.

Who among the contemporary writers do you like and why?

Chandrakishore Jaiswal is among the writers dearest to me. When his story Nakbesar Kaka Le Bhaga was published in Dharmyug, I was mighty impressed with his talent and intellect. Here was a writer from Purnea. After Renu, he is the leading writer in Hindi. He looks like an ordinary man, a typical villager. But he has a marvelous ability to pick things from the ground, from the life of the common people and express them. He doesn’t believe in self-adulation, in advertising his talent. He is miserly with words. He is a very reserved person. In this respect, he is like Jainendra Kumar. He is not at all vocal. And this is his biggest weakness. He is a very good human being. He is my friend and he knows the real meaning of friendship. He has written a lot but sadly he hasn’t got the recognition he deserves. He is almost missing from the contemporary literary scene. But he is still quietly writing long novels and excellent short stories expressive of the feelings of the common people. He doesn’t speak much but his works speak a lot. I consider him a leading Hindi writer.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

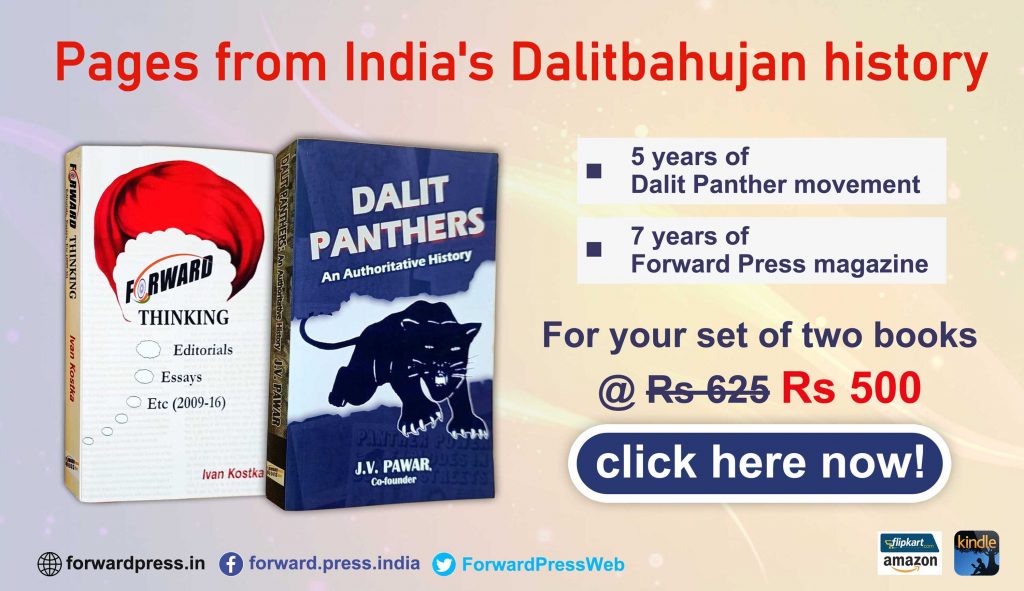

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History