At any mention of contesting elections, often the first question that crops up is where the money will come from. You need money to contest any election – this is a convenient misconception that has been spread far and wide. We must investigate why. Whom does this idea dissuade from participating in politics? The deprived individuals and classes. The misconception about money’s indispensability for politics has been spread by the rich and the upper castes to ensure that the poor and the middle-class don’t even think of contesting elections. What should be kept in mind is that a person’s victory in elections depends on the ideas prevalent in society. The individuals who adhere to the prevalent notions win elections, and the party which believes in those ideas grabs power.

To establish an idea’s influence in society, it is a movement that is required. During the freedom movement, Bal Gangadhar Tilak brought society under the influence of Vedic-brahmanical ideas. After Tilak, Gandhi too infused the Bahujans with brahmanical ideas and beliefs. That was why the Congress ruled the country without a break from Independence up to the year 1965. However, after this, the hold of Gandhism began loosening and because of that Congress governments in different states began tottering.

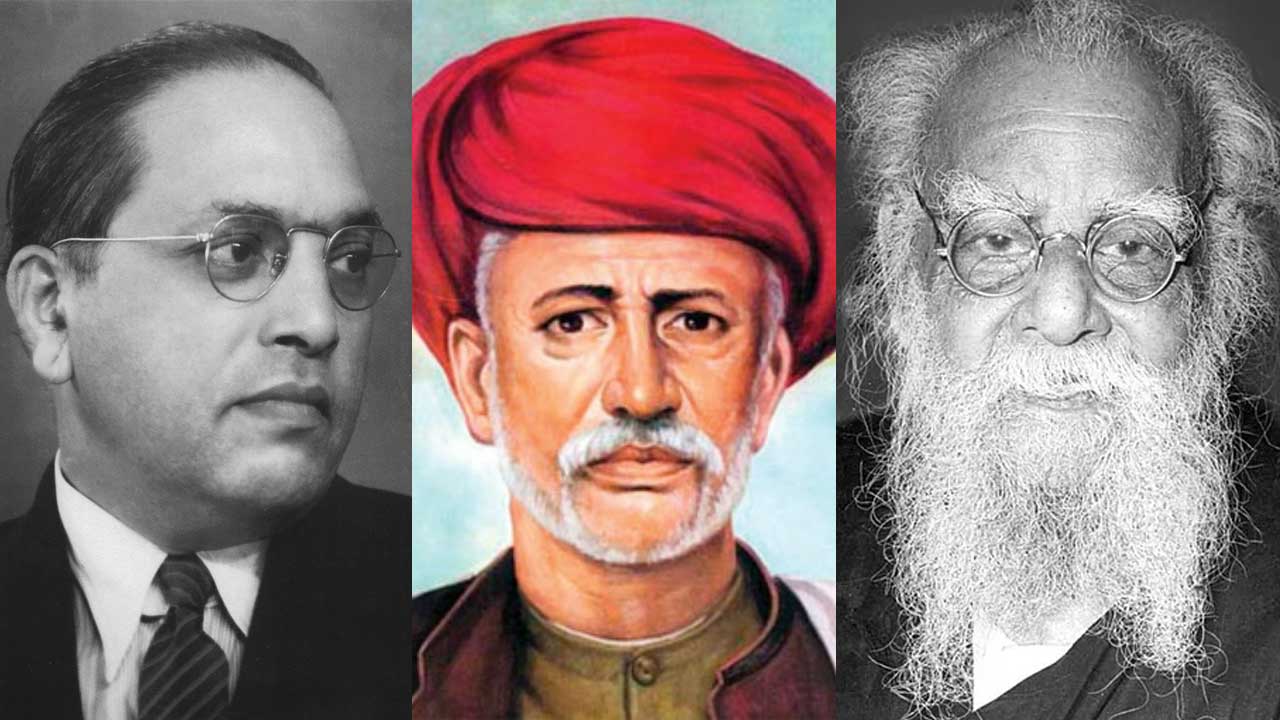

Why did Gandhism lose its sheen? The reason lies in the domain of ideology. Socialism and Marxism posed a stiff challenge to Gandhism. These two ideologies emerged from movements. Before that, Phule and Ambedkar proposed non-brahmanical ideas aimed at annihilating caste to counter the brand of Brahmanism popularized by Tilak and Savarkar at the time.

This ideology too strengthened because of a movement – Jotirao Phule’s Satyashodhak movement. Later, Ambedkar’s anti-untouchability movement turned political with the founding of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and the Scheduled Castes Federation (SCF). In the elections of 1936, 13 of the Ambedkar-led party’s 15 candidates emerged victorious. Likewise, in the Madras province in South India, the Dravida Munnetra Kazgham was founded. It was based on the ideology of Periyar. In North India, Kanshi Ram founded the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) driven by Phule-Ambedkarite thinking.

In the 1920s and 1930s, non-Brahmin political parties posed a cultural challenge to the Brahmanism of Tilak and Savarkar, besides countering them politically. However, the landlords and the feudal Maratha leaders, driven by their lust for power, employed the shortcut of merging the non-brahmanical parties with the Gandhism of the Congress. In 1940, Ambedkar disbanded the politically successful ILP and founded SCF. This experiment failed. Later, the Marxists also challenged the Congress’s Gandhism and that led to the former forming their governments in West Bengal and Kerala. But the Leftist parties have lost their popular base because they went for pure class-based politics and did not assimilate into their ideology the challenge of countering the caste system. The BSP, founded by Kanshiram, was turned into an appendage of RSS-BJP by Mayawati. The socialist parties did manage to taste power but they are also sinking in the morass of casteism.

Ideological movements have catapulted many from poor families to the pinnacle of political power. They include B.S. Venkat Rao (Dhobhi caste) of Andhra Pradesh/Telangana and Gajmal Mali of Maharashtra and OBC leader Karpoori Thakur of Bihar.

In Maharashtra, several OBC leaders from poor families like Bhai Bandarkar and Ganpatrao Deshmukh were elected as MLAs. In 1936, poor Brahmins like Parulekar were returned as nominees of the Independent Labour Party. Ramchandra Ghangare (Teli, OBC), Bhai Mangle (Mali, OBC) and others from poor families became MLAs as candidates of the Communist Party. Mayawati became the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh owing to the Bahujan movement of Kanshi Ram. Bharatiya Janata Party-Shivsena also provided political space to many poor OBCs, Dalits and Adivasis. A former auto driver Eknath Shinde has been appointed as the chief minister of Maharashtra. In Tamil Nadu, OBCs like Karunanidhi and Annadurai became chief ministers.

These examples show that the weight of what you stand for, your ideas, your ideology are most important for winning elections. Ideas ignite movements and movements, not money, change the direction of politics. Thus, the contention that you need tons of money for doing politics is without merit.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Aditya Majumdar)