P.L. Mimroth (10 April 1939 – 24 February 2023)

The passing of Prabhati Lal Mimroth, founder of the Centre for Dalit Rights, has left organizations and individuals working for Dalit rights all over the country in deep sorrow. He breathed his last on 24 February 2023 at around 7.30 am. His body was donated to a medical college in accordance with his wishes. Even in death, he displayed his commitment to the protection of human life and human rights. What is heartening is that his family members fulfilled his last wish, for normally, those who take revolutionary initiatives are often shunned in their own homes and their families do not respect their emotions and wishes.

Mimroth returned to Rajasthan when the state had no organization working for Dalit rights. The Ambedkarite movement was non-existent, and the so-called human rights organizations maintained a stoic silence on the issues of caste and untouchability. In the 1990s, among the organizations working for human rights, the Centre for Dalit Rights emerged as a powerful intervener. I got the opportunity to work with him in the early 1990s. At the time, he lived in Delhi and was a lawyer in the Delhi High Court.

In view of the growing violence against Dalits, Mimroth formed a panel to investigate incidents involving violation of the human rights of Dalits. That extended my association with him. The early 1990s witnessed a political churning in India. The V.P. Singh Government implemented recommendations of the Mandal Commission pertaining to reservations in public employment, which gave a fillip to social and political unity of Dalits and the OBCs at different levels. The opposition to the Mandal Commission in the cities of north India was directed more against Dalits and less against OBCs. The general perception was that the government was already doing much for Dalits. It was the Dalit organizations that took to the streets and it was because of them that the battle became visible. The OBC leadership was largely missing on the ground. In the later years, Ambedkarites like Mimroth began fact-finding to secure justice to the people and brought human rights protectors, lawyers and social activists together to fight cases of human rights violations in courts.

The year 1992 witnessed one of the worst incidents of violence against the Dalits in Rajasthan, when feudal Jats burnt alive 19 Dalits in Kumher village. The incident evoked nationwide outrage but taking a stand against it was still difficult in Rajasthan, because the casteist forces were strong and feudal elements controlled the government. Not one to give up so easily, Mimroth brought together many well-known former judges, lawyers and civil rights workers from all over the country to flag the issue. He fought doggedly for securing justice to the victims of Kumher but Rajasthan’s feudal politics stonewalled all his efforts.

The killers roamed free and atrocities against the Dalits continued unabated in Rajasthan. It was after the Kumher horror that Meemroth became even more active in the state. He founded the Centre for Dalit Rights, made Jaipur his base and through his fact-based investigations into cases of violation of human rights of Dalits, he let the country and the world know what was happening in the state. The new generation of Dalits in the state began asking uncomfortable questions of the establishment. Consequently, today, Ambedkarite missions have a formidable presence even in the villages. Over the course of a conversation about four years ago, he told me: “Initially, I used to work for Dalit rights in Delhi and the neighbouring areas. But coming from Rajasthan as I did, I was well acquainted with the social, political, economic, casteist, geographical and feudal structure of the state. The situation in the state today is much better than what it was prior to 2001. When, in 2001, I began working on issues related to human rights of and atrocities against the Dalits, conditions were very bad. The Dalit victims of atrocities could not even gather the courage to complain. They just kept quiet. If some did muster the courage, cases were not registered by the police. At the time, let alone working for Dalit cause, no organization was willing to mobilize Dalit workers and train them. I faced lots of difficulties. Dalit women social workers were simply unavailable, the reason being that even the educated among them had no platform to have their say.”

I first met Meemroth around 1993, when Ambekarites used to gather and interact on the premises of the Ambedkar Foundation. He proposed the formation of an investigation panel to inquire into the incidents of violence against the Dalits and help the victims during court trials. Being a lawyer, he viewed every such incident from the perspective of the Constitutional provisions. On many occasions, he went on fact-finding missions along with teams of lawyers and former judges. When Dalits were driven out from the “ceiling land” (land under private ownership designated surplus on the basis of an earmarked ceiling and distributed to the landless) in Kashipur of Uttarakhand, Mimroth, his wife Pramila, Namita Rawat and I visited Kashipur. During our probe, we were attacked by a group of Jat Sikhs. Mimroth knew that these things can happen during such visits and so had sought and obtained police security in advance. That was how we could return safely from Kashipur. I pursued the case in different courts for about 25 years and got the ceiling laws enforced. It is another matter that the government created hurdle after hurdle in providing land to the Dalits and even the courts could not reject the government’s contentions.

Prabhati Lal Mimroth was born on 10 April 1939 in Biwai village of Dausa district, Rajasthan. After completing his graduation from Delhi University, he did his LLB from the university’s Law Faculty. From 1959 to 1985 he worked for the Northern Railways. Inspired by Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer, he took voluntary retirement from the railways and began practising law to protect and preserve the rights of the Dalits.

From 1987 onwards, he began pleading cases before the principal seat of the Central Administrative Tribunal in Delhi, the High Court of Delhi and the Rajasthan High Court. He joined different organizations devoted to promoting civil and human rights and social justice. Among others, he worked with the Indian Social Institute, Delhi; Centre for Community Economics and Development Consultants Society; Amnesty International; and People’s Union for Civil Liberties, Rajasthan.

He was one of the founder members of the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights and was its co-convener till 2005, besides being the convener of its Rajasthan chapter. He was also a vice-president of Delhi Legal Aid Society.

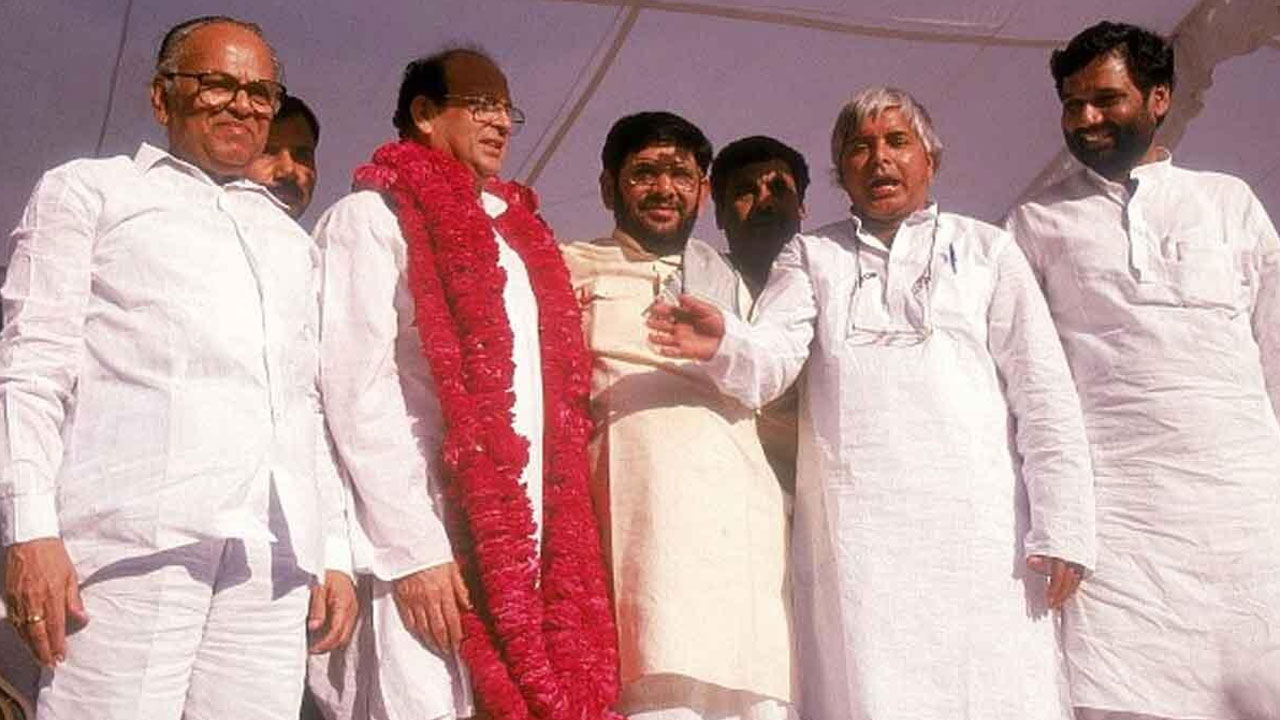

He played a key role in initiating study tours of the villages of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana aimed at identifying and assessing the problems faced by the rural poor. He held several public hearings, seminars and lectures focused on the miserable condition of the Dalit, rural populace of Delhi and Rajasthan, their exclusion, and the problems they faced in accessing justice. Leading reformers, jurists and politicians, besides government representatives, took part in these interactions. They included Justices Rajinder Sachar, V.R. Krishna Iyer, Justice A. Varadarajan, K. Ramaswamy, N.L. Tibrewal and V.S. Malimath, besides Member of Parliament N.H. Kumbhare and famous human rights lawyer Govida Mukhauti.

He keenly followed the implementation of the SC, ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. From time to time, he organized training workshops and lectures for Dalit human rights workers, social activists and others to make them aware of the provisions of the statute.

Mimroth campaigned for Dalit rights in Rajasthan when no one else was doing so. The Centre for Dalit Rights lent a helping hand to a large number of Dalits. He also forged a network of young lawyers to fight for the community rights of the deprived classes. Under the guidance of Mimroth, the Centre for Dalit Rights successfully fought against Dalits being denied access to drinking water in Chakwada.

Today’s generation can learn a lot from him. Institutional efforts, rather than individuals, lend strength to Dalit and OBC movements. Mimroth encouraged youngsters to study law and use their knowledge to campaign against atrocities and injustice. I still remember two things he told me regarding the youth, which are valid even now. He said, “If we really want to restore the lost dignity and identity of the Dalits and the Adivasis, we will have to tap into the energy of the Dalit youth. We need to train the youth in using modern technology and means of communication. I want to tell the young people that today knowledge is power. You should gain complete knowledge of whichever field you choose to join. Only then can you hope to succeed. Dependence on others won’t do. So, my appeal to the Dalit youths is that whether they become politicians, social activists, farmers, officers, entrepreneurs or traders, they should have such mastery of their area of work that people should approach them seeking counsel. Only then can you be successful.”

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)