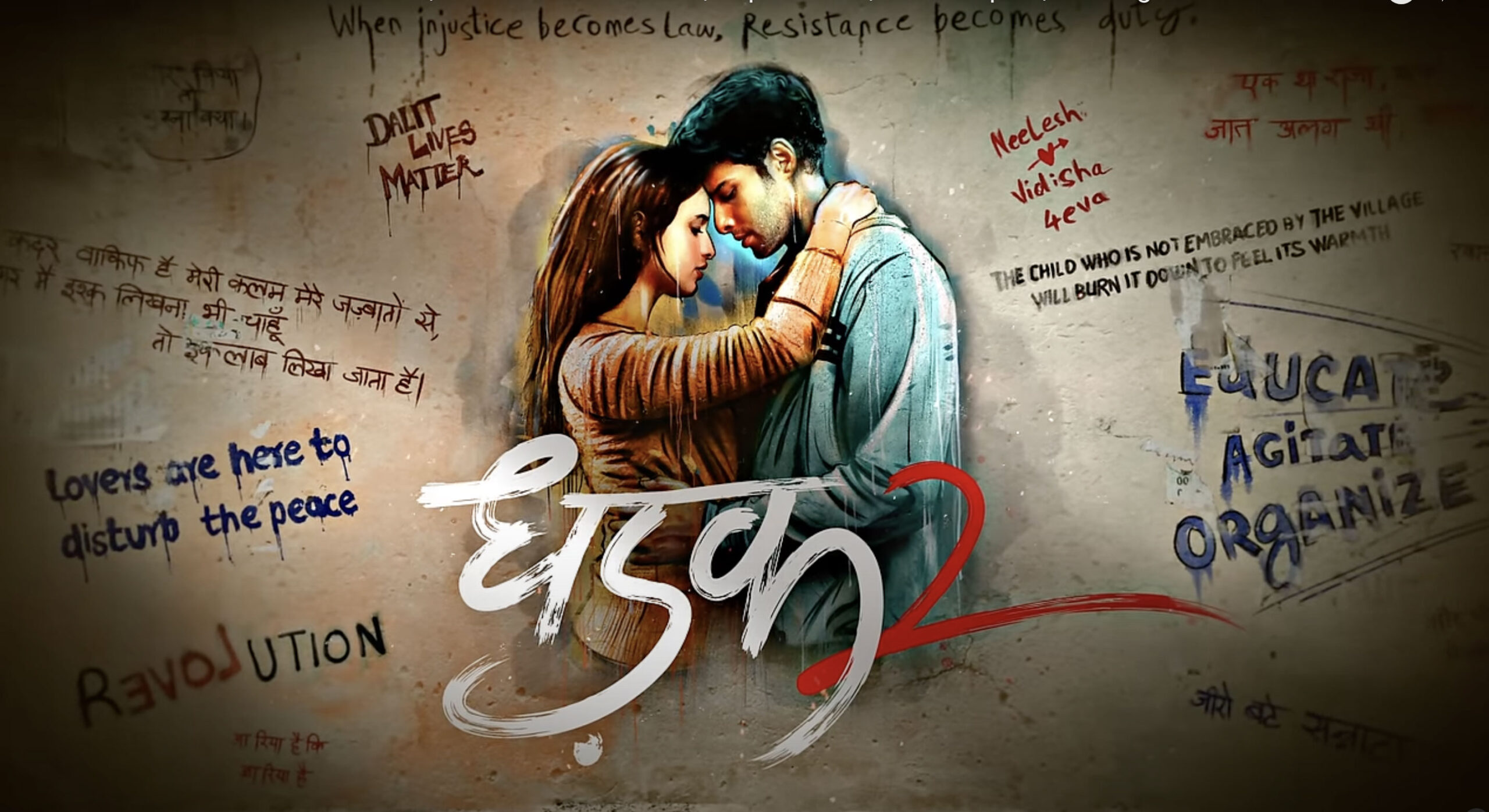

I still remember the first time I watched Pariyerum Perumal in 2018. It was a punch to the gut – a Tamil film, directed by Mari Selvaraj and produced by Pa. Ranjith, that didn’t just tell a story but held a mirror to the ugly reality of caste in India. The tale of Pariyan – a Dalit law student – and his love for Jo, an “upper caste” girl, is raw, heartbreaking and unapologetic. It faced four cuts from the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) back then, but its truth still shone through. So, when I came across CBFC’s recent suggestions for Dhadak 2 – a Hindi remake, directed by Shazia Iqbal and produced by Karan Johar et al, of this anti-caste masterpiece – I felt a mix of anticipation and unease. Dated 22 May 2025, CBFC’s list of 20 modifications for the unreleased film has already sparked a question in my mind: are we ready to face Pariyerum Perumal’s truth in a new language, or will we blunt its edges before it even reaches us?

CBFC’s list does include changes that seem to blunt the film’s edges. Others are routine: blurring alcohol brands at 6:17 and adding an anti-alcohol message at 6:12 – “Sharaab svaasthya ke liye haanikaarak hai” (Consumption of alcohol is injurious to health) – or muting words like “Chamar” and “Be***c**d”. Other changes cut deeper. A scene of a father’s humiliation – which alludes to the visceral shame Pariyan’s family endured in the original – has, according to CBFC, been reduced by “50 per cent”, although it states that the scene has been reduced from 3:11 minutes to 2:56 minutes, that is by 15 seconds. Visuals of a character urinating on Nilesh are removed, and slapping a woman is replaced with black frames.

The dialogue changes, especially those about caste, feel most significant. The line “3000 saal ka backlog hai toh 70 saal mein clear nahi hoga” (A 3000-year backlog won’t be cleared in 70 years) is swapped for “Sadiyon puraana discrimination ka backlog hai 70 saal me clear nahi hoga samjhe” (“Centuries-old backlog of discrimination will not be cleared in 70 years, understand?”). This shift softens the original’s bold confronting of systemic caste issues – a hallmark of Pariyerum Perumal’s impact. Are we protecting audiences from discomfort, or denying them the chance to grapple with a truth that has been centuries in the making?

Another significant edit occurs at 2:11:03, where the original line “Swarno ke sadak… humein jala dete hain” (“The savarna’s streets… they burn us”) is replaced with: “Na sadke hamari thi, na zameen hamari thi, na paani hamara tha. Yahan tak ki zindagi bhi hamari nahi thi. Marne ki naubat aayi toh sheher aagaya.” (“Neither the roads were ours, nor the land, nor the water; even our lives weren’t ours – I was on the verge of death, so I turned to the city.”). Deleting the word “Savarna” (upper-caste) is a way of deflecting responsibility from those who actually inflicted this pain. Whenever a violent incident occurs against Dalits and the perpetrators belong to “upper caste” communities, the casteist media avoids naming them directly. Instead of calling them out, they label the perpetrators as “Dabangg” (dominant or powerful). We often hear in the media that “some Dabangg people assaulted a Dalit man”. This refusal to name the oppressor directly reflects the media’s casteist mindset. In the same way, removing the word “Savarna” in this context reveals the casteist mentality of the CBFC.

Cultural elements, too, are subject to modification. For example, the song “Chitrakoot ke Ghaat Par… Tilak Kare Raghuveer,” originally a couplet by Tulsidas, was translated by the author Ajai Kumar Chhawchharia as: “By Chitrakoot’s sacred riverbank, saints and devotees gather in reverence. Tulsidas prepares a sandalwood paste, and Lord Rama lovingly anoints their foreheads with a tilak.” This was replaced with: “Teer sada woh maariye, keh gaye peer fakir; dekhan mein chhote lage, ghaav kare gambhir” (“Always shoot arrows that may seem small but leave deep wounds.”). This edit shortens the song from 41 seconds to 36 seconds. Along with it, the word “Dharma” (Religion) is replaced with “Punya” (Virtue). This may reflect an effort to remove religious references from a film that critiques caste – perhaps to avoid provoking defenders of brahmanical ideology.

Additionally, the visuals of a poem on a wall were deleted, and its audio was removed. It was replaced with a new poem: “Kua Thakur Ka … Gaav, Shahar Aur Desh” (“The well belongs to the Thakur… as do the village, the city, and the country.”). The original segment lasted 3 minutes and 5 seconds, while the revised version runs for 3 minutes and 16 seconds. The new poem in question could be Thakur ka Kuan (The Thakur’s Well) by Om Prakash Valmiki. However, it remains unclear whether this poem replaced another or was itself altered. If it is indeed Valmiki’s poem and retains its core message and essence, it can expose the harsh realities of caste-based society.

Nevertheless, these seemingly minor changes subtly shift the cultural and emotional tone of the film, potentially influencing how deeply its anti-caste themes resonate with viewers.

CBFC also alters dialogues that convey anti-caste ideology. For example, the original line “Nilesh, ye kalam dekh rahe ho… Raaj kar rahe hain.” (“Nilesh, do you see this pen… they are ruling over us.”) was replaced with: “Yeh chhota sa dhakkan poori qalam ka sirf thoda sa hissa hai, aur baaki ke hain hum – phir bhi yeh hamare sir pe baitha hai. Kyun?” (“This little cap is just a small part of the pen, and the rest of it is us – yet the cap sits on top of us. Why?”) This change dilutes the powerful message popularized by Manyawar Kanshi Ram Saheb, using the metaphor of a pen to awaken his people and explain the dynamics of power and oppression in the political and other public sphere.

Even visual elements face edits – like the removal of the blue tint on a dog at 2:02:59. Surreal imagery works powerfully in Pariyerum Perumal, capturing the spirit and strength of anti-caste assertion and struggle. These changes – amounting to 46 seconds deleted and 2 minutes and 16 seconds replaced – may seem minor, but could end up being significant. Pariyerum Perumal was a battle cry against caste. If Dhadak 2 mutes that cry before its release, are we not losing a chance to confront our deepest wounds – our brutal reality – and the epistemic injustice inflicted upon Dalits and their ongoing fight against it?

I understand the role of CBFC. It’s not entirely their fault – they, too, must fulfil their so-called “social responsibility”. Muting slurs or cutting violent visuals – like the slapping of a woman – might be framed as an effort to prevent harm. Or perhaps, more accurately, to protect the comforts and privileges that caste continues to offer some. But I can’t help thinking of my childhood in a small village, where caste was an unspoken rule – where a surname could define your worth, where tradition crushed dreams. Films like Pariyerum Perumal gave voice to those silences, forcing us to see what we’d rather ignore. I hope Dhadak 2 can do the same for Hindi audiences, despite these cuts.

Still, I dream of a day when cinema can speak truth without restraint – when stories of caste, love and struggle reach us unfiltered. Because if we can’t face these realities on screen, how will we ever dismantle them in real life? I’m waiting to watch Dhadak 2 when it releases, hoping it honours Pariyerum Perumal’s legacy. But with the CBFC’s edits already at work, I fear its flame might die out before it has the chance to truly ignite our screens.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)