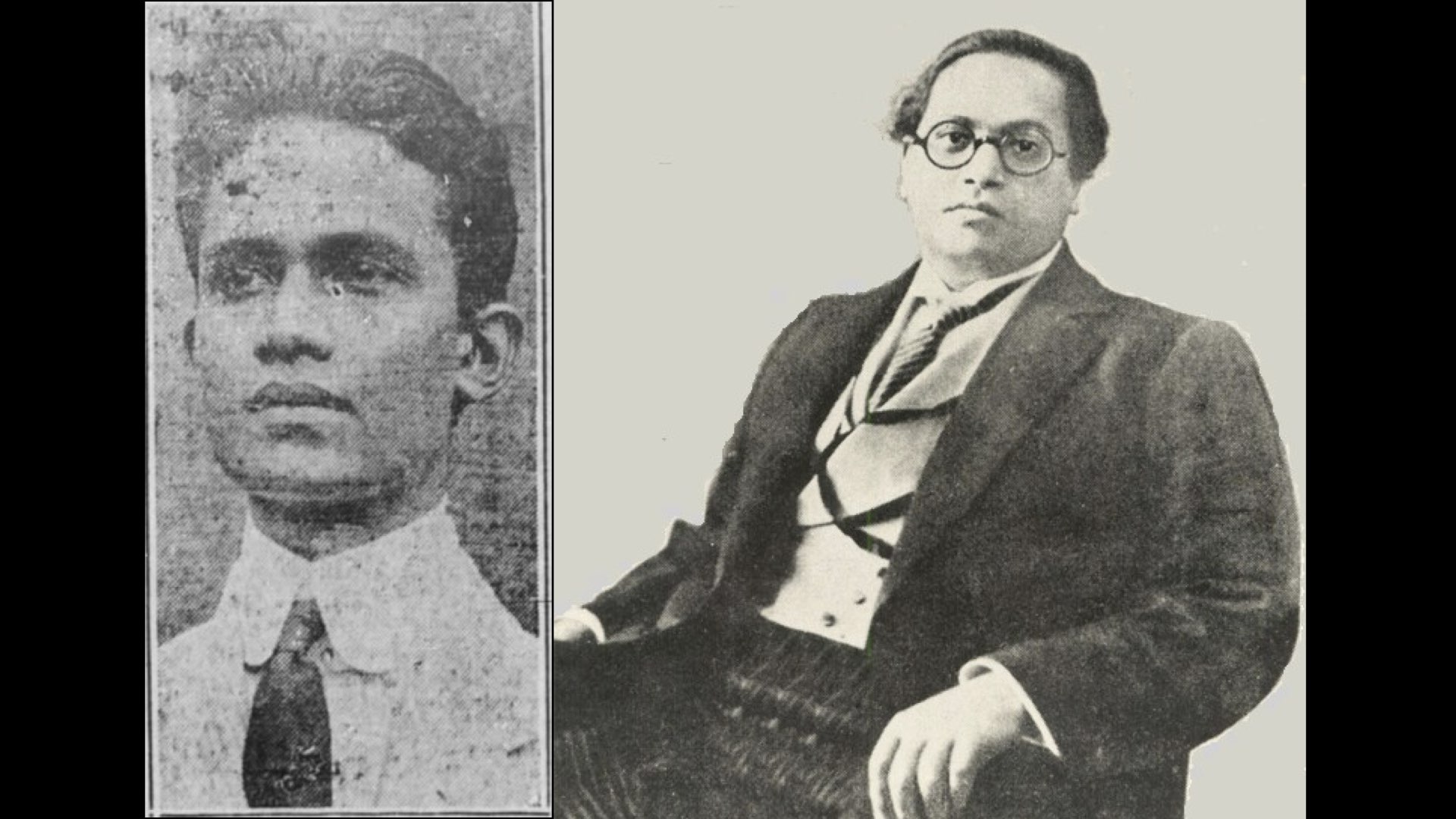

Jagjivan Ram, affectionately known as ‘Babuji’, was one of the top political leaders of his time. Starting out as a Dalit leader he went on to become a respected national statesman.

Despite his immense administrative experience, mass appeal, and leadership qualities, he was denied the prime ministership repeatedly – largely due to the entrenched caste prejudices within India’s political elite. Jagjivan Ram was seriously considered for the post on at least four occasions: 1966, 1977, July 1979 and August 1979.

1966 succession crisis

After the untimely death of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri on 11 January 1966, a power vacuum emerged in the Congress Party. By 14 January, the contest for the leader of the Congress parliamentary party and prime ministership had narrowed down to three frontrunners: Indira Gandhi, Jagjivan Ram and Morarji Desai. Indira Gandhi reportedly had a slight edge over Jagjivan Ram, while Morarji Desai lagged behind. Kamaraj did explore the possibility of bringing about an unanimous decision on Jagjivan Ram as was done when Lal Bahadur Shastri was elected leader, but influential leaders such as Atulya Ghosh and S.K. Patil did not support the idea. With Desai opposing a consensus candidate, Kamaraj ultimately leant towards Indira Gandhi. Realizing that his own candidacy could split the vote and potentially result in Desai’s victory, Jagjivan Ram withdrew from the race and endorsed Indira Gandhi. As a result, Indira Gandhi won the leadership contest in the Congress on 19 January 1966.

Post-Emergency Janata Alliance victory (March 1977)

The second opportunity came after the Janata Alliance’s landslide victory in the March 1977 Lok Sabha elections.

On 18 January 1977, Indira Gandhi announced that the Lok Sabha elections would be held on 20 March that year. But the opposition, with most of their leaders jailed, were low on morale. With the Emergency still on, election only 60 days away and the opposition divided, Indira Gandhi returning to power looked the most possible outcome. Then, the most unthinkable happened – on 2 February 1977, Jagjivan Ram resigned from the Congress and joined the opposition camp – giving a significant boost to the anti-Indira Gandhi movement.

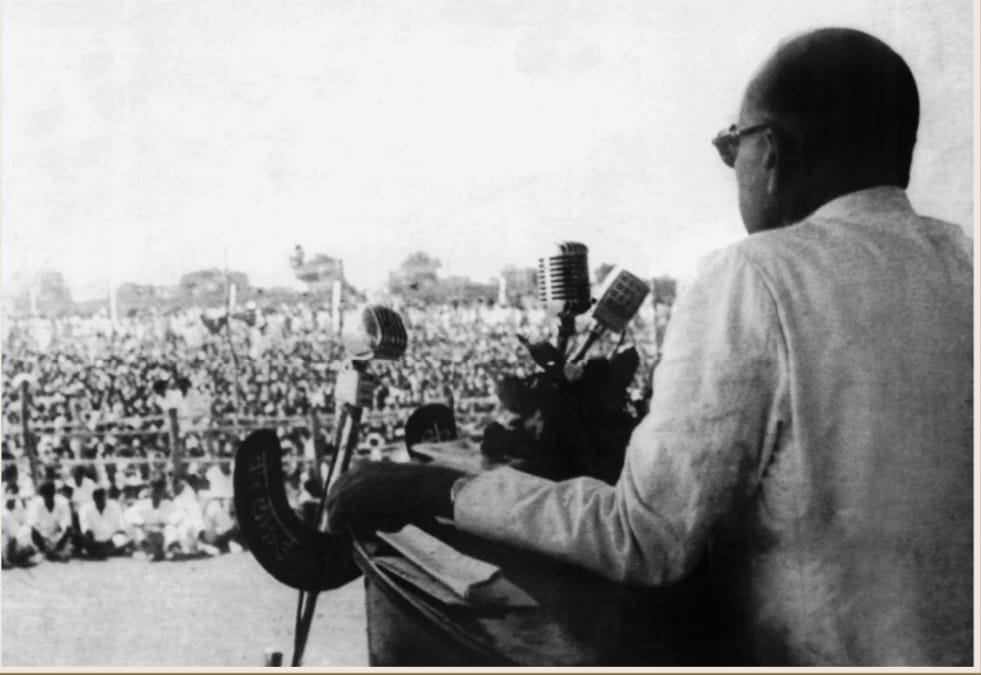

Jagjivan Ram’s bold move to resign from the Congress gave fresh momentum to Jayaprakash Narayan’s movement. His direct opposition to Indira Gandhi electrified the masses. His speeches made a strong appeal to the people, urging them to end the authoritarian rule of “one and a half persons” (Indira Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi) and vote for the Janata Alliance to bring back democracy.

During the run-up to the elections, Jayaprakash Narayan and other leaders said publicly that Jagjivan Ram would become Prime Minister after the elections. His resignation from the Congress was termed as the “J-Bomb” that shook the Congress Party. He was hailed as a messiah who helped restore democracy in the country after the Emergency. He was also seen as the leader who removed the fear psychosis instilled during the Emergency.

The Janata Alliance ended up winning by a huge majority. However, despite Jagjivan Ram’s seniority and pivotal role in the opposition’s electoral success, the prime minister’s post once again eluded him. Charan Singh and Morarji Desai objected to Jagjivan Ram’s potential leadership, because he, as Union Agriculture Minister, had introduced the Emergency resolution in Parliament for its approval. Charan Singh even checked himself into a hospital, feigning illness, to avoid having to back Jagjivan Ram. Instead, Raj Narain, acting as his messenger, delivered a letter to Jayaprakash Narayan, and veteran leader Acharya J.B. Kripalani announced Morarji Desai as the leader of the Janata Alliance’s parliamentary party. Morarji Desai could never become Prime Minister if the MPs had been allowed to vote, so Jayaprakash Narayan nominated him. Jagjivan Ram’s exclusion was widely perceived as the result of an upper-caste political conspiracy.

In protest against the undemocratic selection process, Jagjivan Ram initially refused to accept a ministerial position. However, after repeated requests from national leaders including Jayaprakash Narayan, and student demonstrations demanding that he join the government, he eventually relented and took oath as a minister.

Jayaprakash Narayan should have ensured a democratic election for the leader of the Janata Alliance’s parliamentary party. In his book ‘Ek Zindagi Kafi Nahi Hain’, eminent journalist Kuldip Nayar wrote, “Had there been an election, Jagjivan Ram would have won, as the majority of Lok Sabha members supported him.”

It seemed Jayaprakash Narayan was in a dilemma over Jagjivan Ram. He may have feared that electing Jagjivan Ram could take the Janata Alliance apart, as both Morarji Desai and Charan Singh were not willing to work under him. He felt Jagjivan Ram would be more understanding than Morarji Desai and Charan Singh. The rash, undemocratic decision however was not in keeping with Jayaprakash Narayan’s stature.

When some journalists in Patna asked Jagjivan Ram how he felt in the Janata Alliance, he replied with frustration: “Earlier, I was on the pan; now I have fallen into the fire.”

Even today, Jagjivan Ram’s historic decision to leave the Congress Party in February 1977 is widely praised. But at that time, the hunger for power among some Janata Alliance leaders led them to disregard Babuji’s critical role. If Jagjivan Ram had not left the Congress, the country could have taken a different political direction. His contribution to saving India from autocracy remains undervalued and is often assessed through a casteist lens.

Many political analysts believe that had Jagjivan Ram become Prime Minister, the Janata Alliance would not have come apart, the government would have remained stable, and Indira Gandhi would not have returned to power. The march towards social and economic justice would have accelerated. The caste-based stigma that plagued Indian politics might have been eradicated.

The 1979 political crisis

Jagjivan Ram was denied the Prime Minister’s post for a third time in July 1979. Yashwantrao Chavan, leader of Congress (Urs), moved a no-confidence motion against the Janata Alliance government on 11 July 1979 and Morarji Desai resigned as Prime Minister on 15 July 1979, before the vote. However, in a controversial move, he also wrote to the President of India stating that, since he was the leader of the Janata Party – the largest party in Parliament – he should be invited again to form the government.

Even after resigning as Prime Minister, Morarji Desai refused to relinquish leadership of the Janata Alliance’s parliamentary party and renewed his claim to form the government. This immoral and arbitrary act drew widespread condemnation.

As Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy described in his memoir ‘Without fear or favour’ that “Morarji resigned from the post of Prime Minister on 15 July 1979 before voting and along with it, he also sent a letter to President of India stating that since he is the leader of Janata Party which had the largest number of MPs, so he should be invited again to form Government as leader of single largest party”. President Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy asked Morarji Desai to submit a list of supporting MPs. Upon verification, several signatures were found to be forged. It became clear that Desai had mischievously submitted a false claim to block Jagjivan Ram from becoming Prime Minister. Chandra Shekhar is also said to have had a significant role in this criminal act.

When Morarji Desai resigned as Prime Minister, most ministers and MPs urged Janata Party President Chandra Shekhar to have him step down as parliamentary leader and allow Jagjivan Ram to be elected. They argued that with Jagjivan Ram as leader, defectors would return, and other parties would offer support. His flexible and skilled leadership could have helped the Janata Party win the support of the majority of the MPs once again. They criticized Morarji’s renewed claim to form the government. They questioned his morality – if he had already resigned, how could he still claim leadership?

Meanwhile, Chandra Shekhar, the young party president, announced that if Jagjivan Ram could be considered for leadership, why not himself? This discouraged Jagjivan Ram and his supporters, who then stepped back from staking their claim.

On 28 July 1979, Charan Singh was sworn in as prime minister. Following intense criticism, Morarji Desai had resigned from the position of parliamentary party leader. Fearing that an enraged Jagjivan Ram might leave the Janata Alliance and destroy it, he was made leader of the parliamentary party.

After withdrawal of support by Congress (I), Charan Singh resigned on 28 August 1979 without proving his majority in the Lok Sabha. Then Congress (I) proposed the name of Jagjivan Ram for prime minister with certain conditions, but Babuji refused the conditional support.

Jagjivan Ram presented his claim to the President of India on 28 August 1979 as the leader of the Janata Alliance. President Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy initially responded positively and called him for a discussion at the Rashtrapati Bhawan. However, shortly after the discussion, the President dissolved the Lok Sabha. At that time, constitutional experts were unanimous in the view that, following Charan Singh’s resignation, the President should have invited Jagjivan Ram to form the government. President Reddy’s actions were widely perceived as reflecting an anti-Dalit bias and a vindictive attitude, stemming from his defeat in the 1969 Presidential Election. As a result, Babu Jagjivan Ram’s chance of becoming prime minister was sabotaged for the fourth time.

In response to the dissolution of the Lok Sabha, Chandra Shekhar remarked that the President of India had acted unconstitutionally by not allowing the swearing in of a “Harijan leader” as prime minister. He even threatened to initiate impeachment proceedings against Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy after the elections. However, critics dismissed his statement as a daydream or even a joke, pointing out that such a move would require a two-thirds majority in Parliament, which was unlikely.

When asked by reporters about Chandra Shekhar’s remarks, Babuji’s retort was whether Chandra Shekhar considered himself a Thakur (Rajput) leader. He attributed the President’s decision to a sense of frustration, caste bias, and the lingering resentment from the 1969 presidential defeat. It became clear that Morarji Desai, Chandra Shekhar, and President N. Sanjeeva Reddy had conspired to prevent Babuji from becoming prime minister.

Future generations will remember how those who overthrew Indira Gandhi’s government under the banner of fighting dictatorship, corruption, and restoring democracy, later betrayed those very values. After their electoral victory, these leaders became authoritarian, indulged in internal power struggles, and encouraged corruption at the highest levels. Their infighting, reminiscent of the Mahabharata, exposed their greed for power. The public began to view them as disorganized and opportunistic, and the revolutionary spirit of the Janata Party soon collapsed. Eventually, after two and a half years, Indira Gandhi returned to power in January 1980.

After the dissolution of the Lok Sabha in 1979, Congress (I) President Indira Gandhi had reiterated that her party had wanted Jagjivan Ram to become Prime Minister, but that his own Janata Alliance and President Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy had come in the way. Before the 1980 mid-term elections, Congress (I) invited Jagjivan Ram to return to the party and even offered him the prime ministership after the election. However, Jagjivan Ram declined the offer. Chandra Shekhar and Morarji Desai had convinced him to lead a depleted Janata Party instead.

Jagjivan Ram’s repeated sidelining, despite his qualifications and mass appeal, underscores the deep-rooted caste barrier in Indian politics. His story is not merely one of personal loss but reflects a broader societal failure to rise above prejudices. Had he not been from a Scheduled Caste, there is little doubt he would have become Prime Minister of India. His experiences stand as a stark reminder of how caste discrimination can obstruct even the most deserving individuals from achieving the highest office in a democratic setup.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)