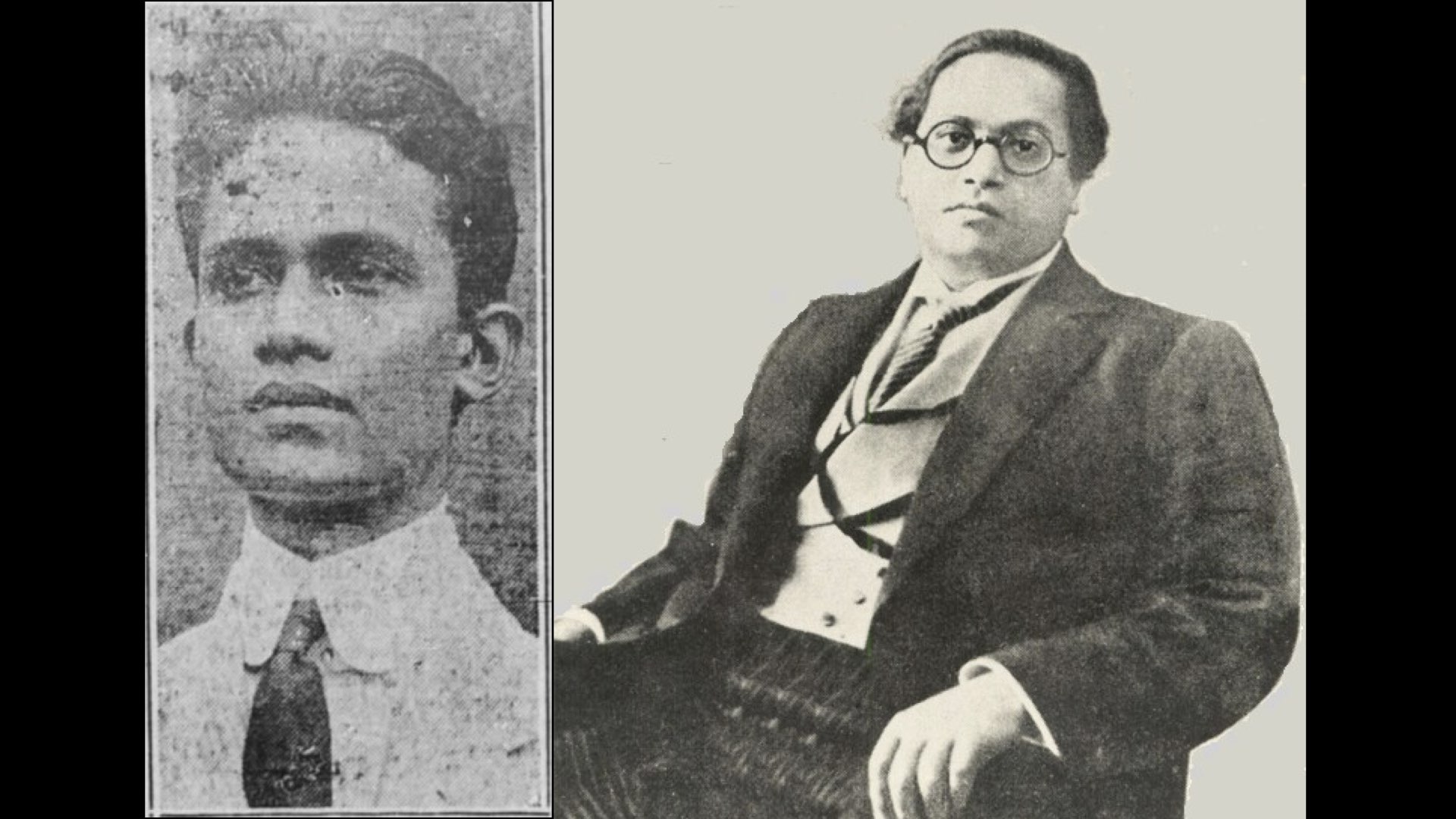

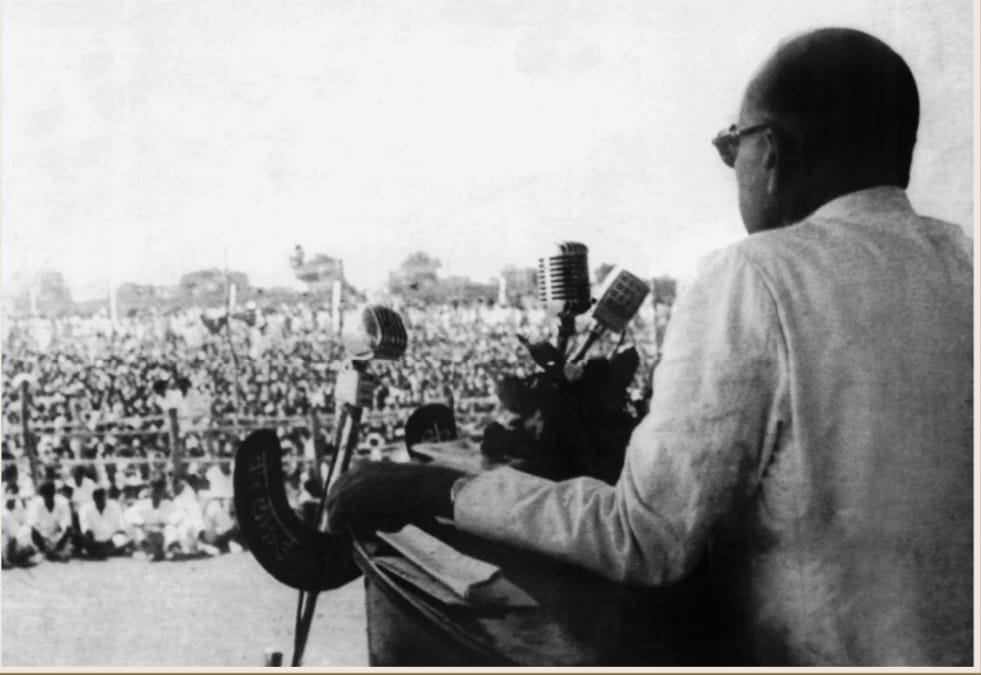

On 13 February 1938, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar delivered a historic speech in Manmad. A pandal was erected for the conference near the Manmad railway station in Nashik district and the venue was named “Dalit Kamgar Nagar”. The Dalit workers of the Great Indian Peninsula (GIP) Railways regularly faced caste oppression. To the fellow workers of the GIP Railways, they were literally untouchable. In light of these conditions, Ambedkar was invited to suggest a way out of the systematic and structural caste oppression. Thousands of workers from Manmad, Bhusawal, Igatpuri, Nandgaon, Thane and Mumbai attended the conference.

When Ambedkar began speaking, the first concern he raised was how Depressed Classes have not yet put significant efforts in rectifying their material conditions. He didn’t just mean that they needed to prioritize their economic well being. Instead he argued that such a struggle should incorporate a struggle to secure social and political interests. For him, “political power” was a necessary medium for bringing about social and economic well being. However, political power without working class “consciousness” and “organization” had no meaning.

Ambedkar further responded to the critics who questioned the potentialities of such a conference organized by the Depressed Classes. Labour leaders of the day considered Ambedkar an enemy of the “class struggle” and therefore workers’ unity. However, such idealistic depictions and distortions of the existing material reality by the upper castes didn’t bother him. He said, “There are in my view two enemies which the workers of this country have to deal with. The two enemies are Brahmanism and Capitalism.” Individuals who criticized Ambedkar failed to recognize “Brahmanism” as the other enemy along with “capitalism”. For him, both Brahmanism and capitalism were central to the enslavement of the Depressed Classes. His political opponents couldn’t grasp the root cause of the material exploitation of Dalit workers. Unlike the “economic determinism” of the communists, Ambedkar was able to identify the existing social ideology that facilitated capitalism in India. He further elaborated thus: “By Brahmanism I do not mean the power, privileges and interests of the Brahmins as a community. That is not the sense in which I am using the word. By Brahmanism I mean the negation of the spirit of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity.”

This negation of the values such as liberty, equality and fraternity is prevalent among every class in Indian society. Brahmanism was not specific to any caste or caste group; instead it was omnipresent in Indian caste society. According to Ambedkar, it affected both the spheres of social and civic rights. There exists a clear distinction between social rights and civic rights. Social rights are concerned with social integration. Depressed Classes were forbidden from dining with and marrying members of the other “touchable” castes. Brahmanism went beyond this hierarchy of social stratification. Depressed Classes were deprived of both social and civic rights. Civic rights were dependent on civil liberties. These civil freedoms were denied to millions in India. Ambedkar said, “Use of public schools, of public wells, of public conveyances, of public restaurants are matters of civic rights. Everything which is intended for the public or maintained out of public funds must be open to every citizen. But there are millions to whom these civic rights are denied.”

Ambedkar’s conceptualization of Brahmanism was also an important intervention because he identified the “cultural” and “social” characteristics of production relations in Indian society. Economic opportunities available to Dalit workers in Indian society were dictated by their social location under the caste system whose hallmark was graded inequality. Ambedkar gave the example of Dalit workers employed in the cotton mills of the Bombay Presidency. They were assigned to the spinning department, where the pay was low. They weren’t considered for the weaving department. “The reason why they are excluded from the weaving department is because they are Untouchables and because on that account the caste Hindu worker objects to work with them although he does not mind working with the Musalmans,” said Ambedkar.

In the railways, Dalit workers were largely employed as “gangmen” in the railways, which also was a “low-wage” job. They were even excluded from jobs such as “porter”. The reason was that a porter at times was required to do the work of a servant for the station master. Generally, station masters hailed from high castes and didn’t go near individuals from the untouchable community for the fear of “pollution”. There was no qualifying examination for the job of a clerk in the railways. Non-matriculants were considered suitable for such a job as long as they did not come from an “untouchable” community. Ambedkar further said, “Very seldom is a Depressed Class man employed as a mechanic class. Hardly ever is a Depressed man seen to occupy the position of a mistry. He is never made a foreman, or even a chargeman in the workshop. He is just a coolie and remains a coolie. Such is the condition of the Depressed Class workers in the Railways.”

Further into his address, Ambedkar responded to the accusation of labour leaders that he was sowing divisions among the workers. He exposed the failure of the Indian communists in understanding the realities facing the Indian working class. Ambedkar criticized the Indian communists for taking Marxism as a “dogma”. He said, “Marx never said as dogma that there are only two clear-cut classes in a society namely the owners and workers.” Indian communists failed to understand the graded inequality that regulated the production relations in Indian caste society. Workers were not a “homogeneous” social group. Without addressing the caste-ridden issues of the Indian working classes, labour leaders of the time could never raise “class consciousness” among the toiling masses. Therefore, in a land where each individual has caste consciousness, how can there be any “class consciousness”? Ambedkar said, “The real way to bring about unity is to tell the worker … [that] these social distinctions which result in unfair discrimination are wrong in principle and injurious to the solidarity of workers. In other words we must uproot Brahmanism – this spirit of inequality – from among the workers if the ranks of labour are to be united. But where is the labour leader who has done this among workers? I have heard labour leaders speaking vociferously against capitalism. But I have never heard any labour leader speaking against Brahmanism amongst workers.”

Ambedkar was unambiguous in his assertion that any union which failed to recognize the caste antagonisms present among the workers was destined to be doomed. Unless caste consciousness was eradicated, no class consciousness could be raised. “This antagonism arises chiefly because one section of Labour claims vested rights against another section of Labour namely the Depressed Classes. Nobody wants to create a difference. What we are doing is to recognize the difference and to prevent the difference from working an injustice to us,” argued Ambedkar.

Trade unionism in India

Ambedkar said, “If there is any country where trade unionism was an absolute necessity in my opinion it was India. But as I said today trade unionism in India is a stagnant and stinking pool. It is entirely due to the fact that the leadership of trade unionism is either timid, selfish or misguided.” He identified the two kinds of labour leaders in the Indian context. The first kind were “armchair” philosophers and politicians who only spoke jargon about the working classes. Neither they involved themselves in organizing workers, nor launching struggles against injustice. The second category of the labour leaders, according to Babasaheb Ambedkar, was, “those who are engaged in forming unions for the sole purpose of finding a place for themselves as Secretaries, Presidents or Chairmen”. The third class of labour leaders according to Ambedkar was the communists. He vehemently criticized the Indian communists who were misguided by their idealistic optimism. He even blamed the communist labour leaders for the terrible material conditions of the Indian workers. They were deluded in thinking that only by channeling the “discontent” among the Indian working classes, they could forge a revolutionary action. Ambedkar said, “For a successful revolution it is not enough that there is discontent; what is required is a profound and thorough conviction of the justice, necessity and importance of political and social right.”

Create your own workers union

Babasaheb Ambedkar urged the Untouchable workers to form their own union. He had seen how GIP railways unions breaking up constantly for political and ideological reasons. He believed though that a separate union of the Depressed Classes could make a difference. However, Ambedkar warned them to be cautious against the manipulative tactics of the other unions. The organization should be driven by concrete purpose and concrete action. But that is not enough, Ambedkar said, adding that union workers should also organize for political purposes. Trade unions should enter politics for achieving their material ends. He said, “Trade unions must enter politics because without political power they cannot protect purely trade union interests. Even for the purpose of securing such reforms as standard rate, normal day, common rule, minimum living wage, collective bargaining are aims which cannot be secured merely by organizing unions. The power of unions must be strengthened by the force of law. This cannot happen until in addition to organizing yourselves into unions you also begin to play your part in the politics of the country.”

The aim of the trade unions should be to eradicate wage slavery and fight for liberty, equality and fraternity. This struggle should further aim for building a casteless society. All this could only be achieved through the capturing of political power by workers. It is not enough to rely on organizing workers under the trade union praxis. Any organization of workers, having political consciousness, and still working only as pressure groups, is vulnerable to political suppression. Having said that, organized action requires an organized political party. It depends on the context and content of the political party and the class whose interest they are serving.

There were two major socialist camps at the time, one being the “Congress socialist” faction and the other being the group led by M.N. Roy, the radical humanist and communist stalwart. Roy was vehemently opposed to any independent labour organization in India. For Roy, the major enemy of labour was imperialism and it needed to be fiercely opposed and thrown out by the Indian toiling masses. Ambedkar was opposed to both the Congress socialist camp and Roy’s understanding of the then political conditions. Rejecting Roy’s political praxis, Ambedkar said that “it does not require much intelligence to realize that even if the British depart from India, the landlords, the mill-owners, the money-lenders will remain in India and continue to bleed the people and that even after imperialism has gone, labour will have to fight these interests just as much”.

Ambedkar criticized the Congress socialist group for the reason that Congressmen only wanted a labour organization within the parameters of its political party, leaving no space for the larger working-class unity. He knew that Congressmen talking about socialism was downright hypocrisy and that they had in mind only the interests of the landed upper-caste Hindu elite. Their socialism rang hollow. Ambedkar said, “Indian politics has become wrapped by its reaction to imperialism. Labour is made to forget its real enemy namely the vested interest. Both the Royists and the Congress Socialists are trading in this quagmire because of confusion of thought. Even if imperialism is to be dealt with as the common enemy, it does not mean that all classes must forget class interests and join in one organization. Imperialism could be fought by the different class organizations making a common front.”

Since Ambedkar knew that Indian workers needed an organized political space which could serve their class interests, he had launched the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Congress socialists and Royists were focused on the political scenario whereas Ambedkar’s ILP gave importance to both caste- and class-based concerns. He said, “Politics must be based upon class consciousness. Politics which is not class conscious is hypocrisy.”

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)