In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, two social groups are in the crosshairs of the upper castes and the Bharatiya Janata Party – the party that represents them. They are Yadavs and Ambedkarite Dalits. For now, I am confining myself to the factors behind the hatred that the upper castes of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and the BJP, the political outfit that represents them, harbour for the Yadavs of these two states.

Let us begin with the political reasons. And among them, too, the recent ones. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar together send 120 members to the Lok Sabha – almost 22 per cent of the strength of the lower house. In these two states, only the Samajwadi Party (SP) and the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) are in a position to pose a challenge to the BJP. Both are led by Yadav leaders. In the last (2024) Lok Sabha elections, it was the SP that came in the way of the BJP securing a majority of the seats in Uttar Pradesh. The SP confined the BJP to just 33 of the 80 seats. Clearly, the BJP cannot form a government at the Centre on its own without trouncing these two parties. In other words, they are the two biggest hurdles in the BJP’s path. They haven’t allowed the BJP to dominate the Hindi belt.

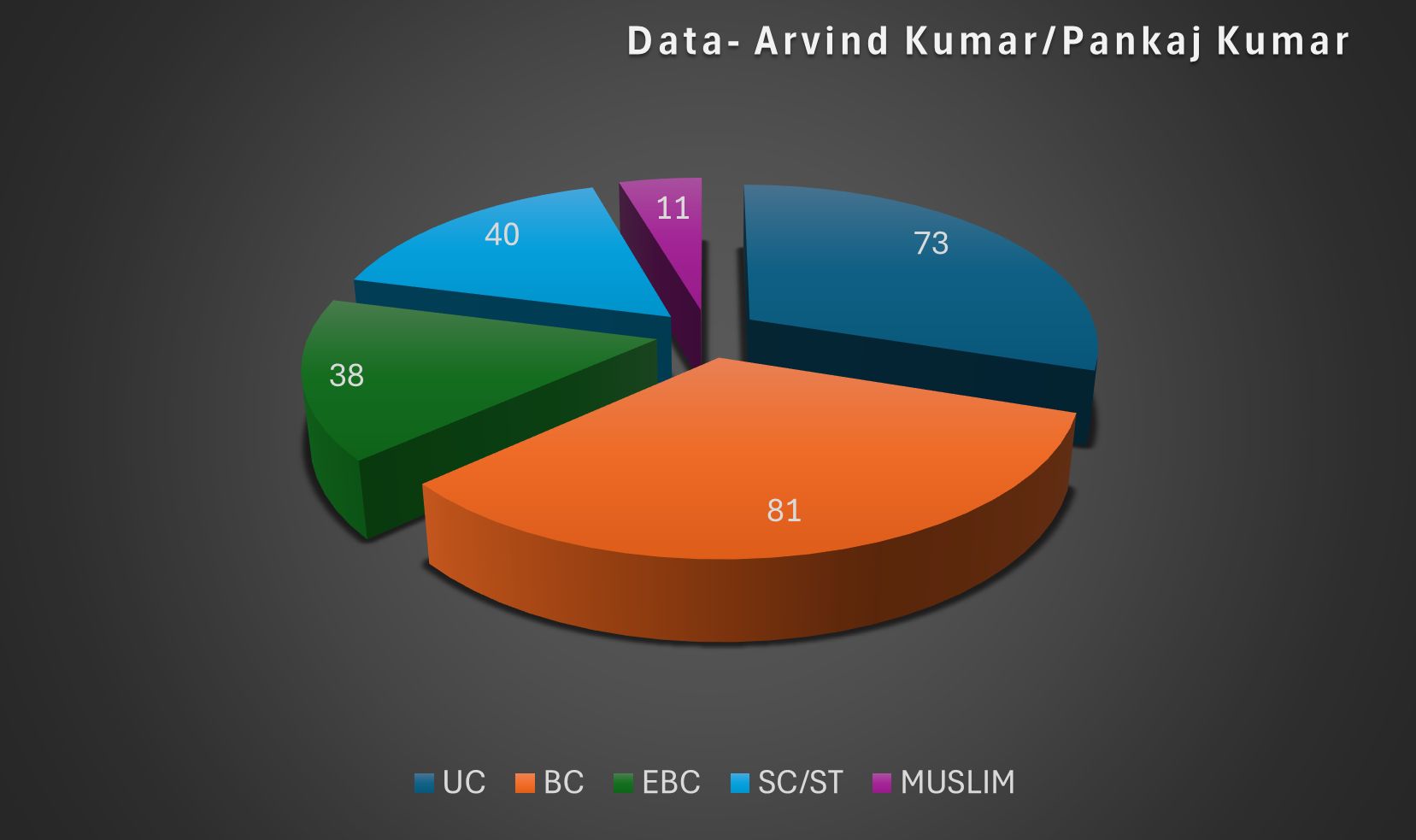

In both the states, the upper castes have firmly stood by the BJP. According to the Lokniti-CSDS Survey, in the last Lok Sabha elections, 89 per cent of the Brahmins and 80 per cent of the Rajputs voted for the BJP. Despite that, the BJP could win three seats less than the SP. Additionally, the Congress managed to win six seats with the help of the SP. BJP’s defeat in Uttar Pradesh was perceived by the upper castes as their own defeat. The BJP’s loss in Ayodhya was catastrophic for them. In Bihar, too, the upper castes are inclined towards the BJP and they see the party’s victory or defeat as their own.

Barring Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, since 2014, the Hindi belt has emerged as an impregnable fortress of the BJP. The BJP has been winning a majority of the Lok Sabha seats in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Delhi, even if in some of these states the Congress did manage to form its governments for short durations.

Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, however, continue to be a conundrum for the BJP. Even in the assembly elections in these states, the SP- and the RJD-led coalitions have been posing a challenge to the BJP. In the 2020 Bihar Assembly elections, the RJD-led Mahagathbandhan almost succeeded in defeating the NDA. The Mahagathbandhan was kept out of power through machinations involving the electoral and the administrative machinery. The difference in the votes garnered by the two alliances was just 12,000.

It is thus apparent that in the Hindi belt in general and in large, populous states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in particular, the RJD and the SP have posed the stiffest challenge to the BJP. The BJP wants to establish its complete dominance in this region. Concurrently, the upper castes, the core support base of the BJP, see the Yadavs as their chief challengers. No wonder, the BJP and its core supporters want to weaken or preferably finish off these two parties and their leadership. These two parties are also key hurdles in the Hinduization of the people of these two states and consequently for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Bharatiya Janata Party’s long-term project of turning India into a Hindu Rashtra.

Tore into political domination of upper castes

Yet another reason for this animosity is that barring the SP and the RJD, almost every regional party of UP and Bihar has, at one time or the other, climbed into the lap of the BJP. The BJP knows pretty well that the leadership of these two parties would never align with it. The reason for this is not far to seek. For one, Muslims are major backers of these parties and there is no love lost between the Muslims and the BJP. It is highly unlikely that the RJD and the SP will join hands with the BJP at the cost of losing their support base among the Muslims.

In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the Muslim voters have been supporting these two parties for a long time. The Muslim voters feel that in Bihar only the RJD and in Uttar Pradesh only the SP can pose a challenge to the BJP – a party bent upon pushing them to the margins and working constantly to realize its dream of a Hindu Rashtra. And that makes sense. The BJP has successfully relegated the Muslims to the margins in other Hindi-speaking states. But if Muslims have, to some extent, succeeded in saving themselves from becoming politically irrelevant in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, it is only because of these parties. In the two states, the SP and the RJD have forged a strong political bond between the Yadavs and the Muslims. The association of these parties with the Muslims is a thorn in the flesh for the BJP. But for it, the BJP would have pushed Muslims into political oblivion long ago. The BJP and the upper castes deeply resent these two parties, their leadership and their core voters – the Yadavs.

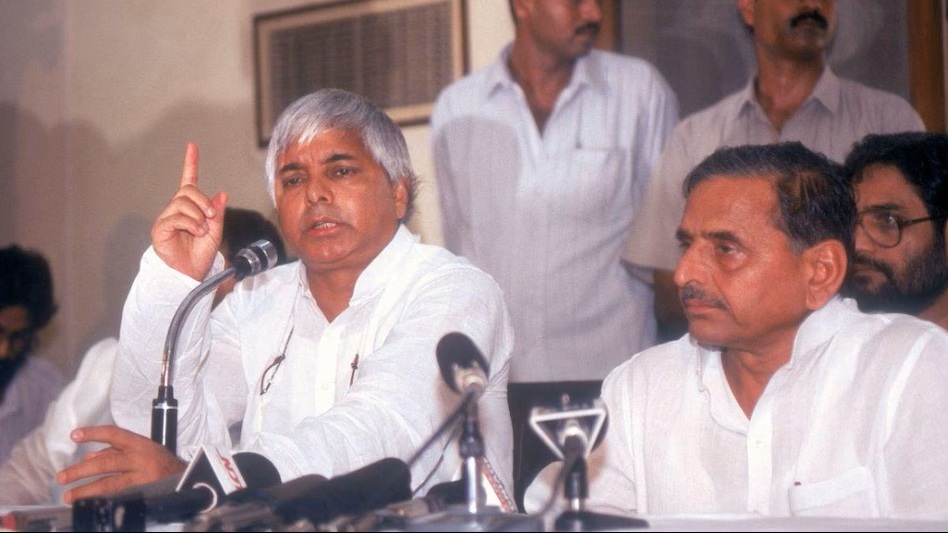

There is more to BJP-Yadav antagonism. The Yadavs had bitterly opposed the BJP’s campaign claiming that the Babri Masjid was built on the debris of a Ram Temple. Two Yadavs – Lalu Prasad and Mulayam – came in the way of the BJP’s political campaign to build a Ram Temple where the Babri Masjid stood. Mulayam Singh was branded as a killer of Hindus. The upper castes and the BJP began calling him “Mulla Mulayam”. Lalu’s role was no less. He stalled Lal Krishna Advani’s Rathyatra and arrested the top BJP leader. Lalu opposed the Ramjanmabhoomi movement tooth and nail at every level.

In the Hindi belt, only two parties – RJD and SP – and only two leaders – Lalu Prasad Yadav and Mulayam Singh Yadav – bitterly and unambiguously opposed the Ramjanmabhoomi movement. The Congress never took a clear and decisive stand on the issue. When Babri Masjid was torn down, the Congress was in power at the Centre. The Congress Government, led by Naramsimha Rao, was a mute spectator to the destruction of the Babri Masjid. It did nothing to stop it. But during the entire Ramjanmabhoomi movement, Lalu and Mulayam thwarted the designs of the BJP-RSS combine. They were a pain in the neck for the saffron front.

Yet another reason is that Mulayam and Lalu were the first to deal a fatal blow to the political domination and control of the upper castes in their respective states. Under the chief ministership of Ajay Singh Bisht alias Yogi Adityanath, the domination of the upper castes may have been restored in Uttar Pradesh and the recent polls in Bihar may have thrown up an assembly with a remarkable jump in the number of upper-caste members and that may reflect in the composition of the council of ministers, too, yet the fact remains that it was Mulayam and Lalu who had freed their respective states from the political stranglehold of the upper castes for an extended period of time.

It is not as if these states never had chief ministers from lower castes before Mulayam and Lalu. They did. But those chief ministers were not in absolute control of their parties and their government. They were not in a position to decide whom to field in elections, whom to get elected to legislative assembly, whom to send to legislative council or Rajya Sabha and whom to pick as ministers. Lalu and Mulayam had no supremos above them. They were themselves the supremos. They were the first chief ministers of their states who could have their way, who could take independent decisions and who were not controlled by the upper castes.

Simply put, these two leaders and their parties were the first to end the political domination and control of the upper castes in their states. The upper castes haven’t forgiven them for this “crime”. In Uttar Pradesh, when the SP and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) were competing for the same political space, the upper castes aligned with the two alternately. And the SP did take some anti-Dalit steps to keep the upper castes in good humour. But as soon as the upper castes got a viable alternative in the BJP, they deserted the SP and BSP and jumped on the BJP bandwagon.

Social factors also fuelled hatred

The Yadavs of the two states – especially Uttar Pradesh – not only put an end to the domination and control of the upper castes in the political arena, but they also challenged them socially in villages and small towns. In the rural areas, if the upper castes fear any community, it is the Yadavs. Due to many reasons, the Yadavs were in a position to take on the strongmen at village and local levels and even make them bite the dust. The Yadavs challenged and even defeated the upper castes in elections of village pradhans and members of the gram panchayats, district panchayats, municipal committees and even municipal corporations of big cities. In villages – the primary units of the country – it was the Yadavs who posed the biggest challenge to the upper castes. They hit back at the upper castes – matching the latter in tone, tenor and action.

Ambedkarite Dalits have been the biggest challenge for the upper castes in ideological and cultural terms and continue to be so. However, they lack the muscle and money power needed to take the upper castes head-on. Moreover, the Dalits, for a long time, were completely dependent on the upper castes for livelihood and to a great extent still are. But the Yadavs, involved in farming and animal husbandry, are not as dependent on the upper castes.

The political rise of Mulayam Singh Yadav and Lalu Yadav lent strength to the Yadavs. Using their influence and power, the Yadavs managed to corner government contracts and buy shops, land, trucks, buses and so on and start businesses. This broke the economic monopoly of the upper castes. Their economic and political prowess together enabled them to stand up to the upper castes. Sometimes they won, sometimes they lost. But the upper castes could no longer be assured of a walkover.

The Yadavs played a key role in disrupting the societal dominance of the upper castes in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. No longer do the upper castes rule the villages. Of course, many different organizations, social groups and struggles and conflicts have contributed to bringing about this societal transformation. But the Yadavs were its chief architects.

Ending intellectual hegemony

The Yadavs also played a key role in ending the intellectual hegemony of the upper castes. It is an established fact that the monopoly of the Brahmins in the intellectual arena faced challenges from the likes of Phule, Ambedkar and the Dalit and OBC adherents of Periyar’s ideology. But the Yadavs led among the OBCs in producing intellectuals. Yadavs, equipped with Bahujan, leftist or Lohiate ideologies, have made their presence felt in the universities and colleges and in the fields of culture, literature and journalism. They have challenged the upper castes intellectually.

Moreover, the attitude of the Yadavs towards Brahmanical rituals and their relations with Brahmin priests have been different from those of the farmers of other OBC castes.

I can say from my personal experience that the Yadavs are not as enamoured of Brahmanical rituals as other OBC peasant communities are. They do not revere Hindu deities as much as other farmers do. Yadavs do invite Brahmins to conduct religious rituals, but they don’t accept their hegemony. If needed, they don’t even refrain from slapping the priest. One reason for this is that they are cattle-rearers. They were different from other relatively prosperous castes among the Backwards. That was probably why they could free themselves from the domination of the upper castes and challenge the latter. The rise of Mulayam and Lalu and the stiff challenge posed by Hindutva politics led to the Yadavs breaking free from the stranglehold of the upper castes. They took political and social initiatives independently and became economically stronger. This, despite the fact that Yadavs did not hold as much farmland as other peasant communities among the Backward classes.

Lack of alternative discourse

Though the Yadavs and their leaders successfully breached the sociopolitical, and to some extent the economic citadel of the upper castes, they lacked in two respects. One was that both the leaders (Mulayam and Lalu) could not come up with an alternative to the socio-cultural-economic discourse of the upper castes. They did depose the upper castes from the pinnacle of politics, but unlike the Bahujan political outfits of Tamil Nadu (DMK and AIADMK), they could not devise an alternative programme or discourse to end the socio-political and economic domination of the upper castes for good. The principal reason for this was that, let alone Phule, Ambedkar or Periyar, their ideology was not even rooted in the thinking of Jagdeo Prasad, Ramswaroop Verma, Periyar Lalai Singh and Triveni Sangh from the Hindi belt. They could not even associate themselves with Karpoori Thakur and the Mandal Commission. That led to their political initiatives losing steam. They did challenge the upper castes – and continue to do so – but they could not forge solidarity rooted in equality, justice and brotherhood with the extremely backward classes and the Dalits. While they did challenge and managed to deal deadly blows to the domination of the upper castes, they also sought to make other non-Savarna social groups subservient. This could have happened consciously or unconsciously but it did happen. And the upper castes, which already despised them, took full advantage of it. The rivalry between the relatively prosperous castes of the backward classes helped the BJP and the upper castes create an atmosphere against the Yadavs. Psychology tells us that the rise of one among us affects us more deeply and causes more envy than the growth of others. And even if stalling the rise of our own people involves joining forces with the power-hungry, so be it. That was what the non-Yadav OBC castes did.

Implications of anti-Yadav narrative

Notwithstanding these weaknesses and limitations, the fact remains that the Yadavs and the parties led by them (RJD and SP) ended the political hegemony of the upper castes. And even now, they pose the biggest challenge to the BJP – which represents the interests of the upper castes – in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Only they are capable of halting the juggernaut of Hindutva politics in these states. It is because of the Yadav-Muslim alliance and the opposition of Yadav-led parties to Hindutva politics that the savarnas, their intellectual-cultural wing and their party – the BJP – harbours such deep hatred for the Yadavs and their parties. They want to cripple them. In fact, they want to end their existence as a political force. The upper-caste ecosystem is dead set against them. They have been trying to defame them. They have been trying to cut them off from the other OBCs, EBCs and the Dalits. Needless to say, the weaknesses and the failings of these parties are playing into their hands. But it is a fact that the upper castes and their patrons – the BJP and the RSS – have been building an anti-Yadav narrative in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. They know that but for these two parties, they would have dominated the Hindi belt. That is why they continue to malign Yadavs and the SP and the RJD day and night.

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in