Addressing the Constituent Assembly on 25 November 1949, Dr Ambedkar had said:

We must not be content with mere political democracy. We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. What does social democracy mean? It means a way of life which recognizes liberty, equality and fraternity as the principles of life. These principles of liberty, equality and fraternity are not to be treated as separate items in a trinity. They form a union of trinity in the sense that to divorce one from the other is to defeat the very purpose of democracy. Liberty cannot be divorced from equality, equality cannot be divorced from liberty. Nor can liberty and equality be divorced from fraternity. Without equality, liberty would produce the supremacy of the few over the many. We must begin by acknowledging the fact that there is complete absence of two things in Indian society. One of these is equality. On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics, we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy which this Assembly has so laboriously built up.

In real life, both social and economic equality is a utopia but attaining it is and should be the ideal of every society. But the question is: can a utopia ever be an ideal? The answer is that it can and should be, for it would be immoral on our part to accept social and economic inequality as inevitable. If we presume that no society can become perfectly equal then we will lose the inspiration and the zeal for doing something new, for bringing about a change. Thus, even while knowing that an equal society will never be created, we should continue to urge people to keep on marching towards it. It is by pursuing this utopia that India’s exploited, the deprived and the backward have achieved so much growth and progress and are brimming with hope. In any society, resources are limited and have to be shared by everyone. The conflict in Indian society is born of this competition for grabbing resources. It will be wrong to see this conflict only through the prism of religion or caste.

That is why I do not see the violence in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh, in April-May 2017 as casteist violence. It was not that straightforward. Caste was neither at its root nor was it its target. But despite that, we will have to call it casteist violence in the Indian context for want of a better word.

We cannot even conclude that any particular caste or group is prone to violence. In Saharanpur, both the Jatavs/Chamars and the Rajputs committed violence. What was at the root of this violence? It is easy, safe and entirely acceptable to describe it as casteist violence. However, for a proper analysis of the events, we would have to look at other factors too.

If we analyze the chain of events minutely, we will discover that the issues of identity and dominance played as important a role as – if not more than – caste. Identity is both social and cultural. In today’s India, caste has also become synonymous with social and cultural identity. In other words, this violence would have taken place if, other things being the same, only the factor of caste were missing – ie, Saharanpur would have witnessed bloodshed even if there were no institution, culture or system like caste. All these are subsumed in caste in India but when we used the word caste, we do not pay adequate attention to the other factors; we do not realize that caste is also defined by certain socio-cultural factors.

Shabirpur did not take place because of Rajput pride, but because Rajput pride was challenged. The seeds of the violence had been sown much earlier. It will be pertinent to mention here that the post of pradhan of this village is unreserved. The savarnas consider any unreserved post as reserved for themselves. But an SC was elected as the Pradhan. This was not palatable to the Rajputs.

Ignoring the tenets of Brahmanism, the residents of Shabipur had a Ravidas temple built and all public social events were held on the premises of the temple. The SCs wanted to install a statue of Ambedkar on the premises. They did not want to install it in a public place that they shared with the Rajputs and others. However, the spot where the statue was to be installed would have made it visible to passersby on the road. The Rajputs did not want to see Ambedkar’s statue whenever they passed the temple, so they had the administration intervene and stop the building of the statue. When we spoke to the district magistrate on 18 May, he told us that prior permission was mandatory for putting up any statue and that the SCs had not adhere to the rules.

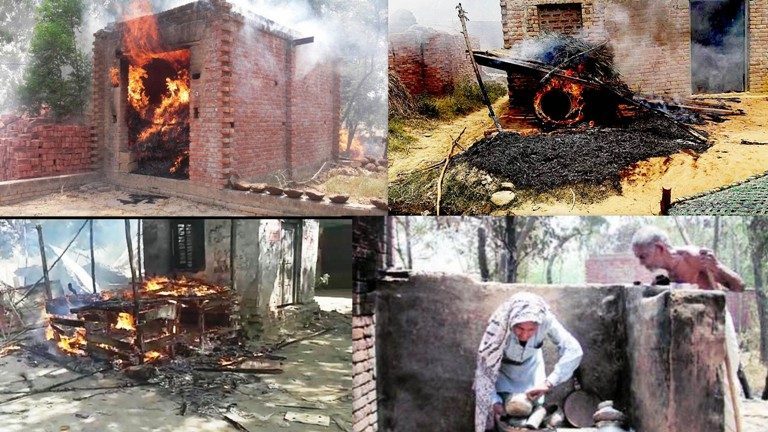

The Maharana Pratap Jayanti programme was held on the premises of the Maharana Pratap Degree College in Shimlana, about 5km from Shabirpur. Some Rajputs had assembled in Shabirpur before heading to Shimlana to attend the programme. The SCs objected to the Rajputs taking out a procession with the statutory permission, so they informed the local police, who arrived at the spot. According to the SCs, the Rajputs were raising slogans like “Har-har Mahadev”, “Jai Shriram, Jai Maharana”, “Maharana Pratap Ki Jai” and “Ambedkar Murdabad”. Both the groups threw stones at each other and a Rajput youth had to be rushed to the hospital, where he died. The news of this death reached the people attending the Maharana Pratap function in Shimlana. Sher Singh Rana, murderer of the revolutionary Phoolan Devi, was at the programme as a special guest. He challenged the gathering by saying, “Our brother has died and you are holding a meeting.” A large number of Rajputs responded to his call and left for Shabirpur and ended up burning down houses there. According to the locals, the Rajputs were armed. Many people were injured and were admitted to hospitals. The police was present when the Rajputs ran amok. No SC was killed in this incident though.

It may also be mentioned here that such incidents of arson by dominant castes against Dalits have been reported from Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Haryana and many other states. In all such incidents, the homes of the Dalits were looted so as to cripple them economically but no one was killed. In Bihar there have been cases where the head of the family was murdered but there too the objective was to deprive the family of its earning member. Thus, these kinds of incidents are aimed at ensuring that the Dalits cannot become economically empowered.

‘The Great Chamar’ of Ghadkauli

Last year, the residents of Ghadkauli, another village in Saharanpur, rechristened their village as “Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar Gram”. They put up a signboard that said “The Great Chamar: Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar Gram”. The Rajputs objected to it, to Chamars describing themselves as “great”. The residents said that the Rajputs had removed the signboard but they had put it up again. The matter was not reported to the police but the Dalit youth maintained a 24-hour vigil to ensure that the board was not removed or damaged. The Rajputs complained to the police that the signboard had been put up on government land. But the police, on enquiry, found that the land was privately held. According to the residents of the village, Rajputs had beaten up Dalits in the presence of the police. The residents of “Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar Gram” say that the savarnas had given them the name “chamar” to humiliate them. But why should they feel humiliated or inferior because of the name of their caste or the nature of their work? They say that they are proud of their caste and their profession.

Things do not end here. The SCs say that their being Hindu was at the root of their humiliation. To protest the police action against the Bhim Army, they announced that they would quit the Hindu religion and embrace Buddhism. On 18 May 2017, around 180 SC families of Roopdi, Kapurpur and Eeghri villages of Saharanpur went to a canal near Maankamu and dumped the calendars carrying photographs of Hindu gods and goddesses and images of Hindu deities. During the demonstration at Jantar-Mantar in Delhi, many of the Dalits threw away the “kalawas” (sacred threads) they were wearing on their wrists and removed their “kadas”.

Responding to the Bhim Sena’s call, most of the villagers started sending their children to private schools because, according to them, the standard of education was very poor in the government schools. Some Dalits have started giving tuitions to the children of their community for free.

This socio-cultural impact of Ambedkarism is challenging the traditional social order. On 16 May 2015, Sagar Sejwal was killed in Shirdi, Maharashtra, because the ringtone of his mobile hailed Ambedkar. The violence on JNU campus in October 2012, the seizure of the copies of FORWARD Press by the police in October 2014 and the melodramatic speech of Smriti Irani in Parliament in February 2016 – all had a lot to do with the rise of a new symbol in the form of Mahishasur and the religio-cultural challenge it was posing. The violence by Rajputs in Saharanpur is also the fallout of the socio-cultural challenges they are facing.

How to see the incident?

A crisis of identity is behind the Rajputs attacking SCs in different parts of Saharanpur. They have a self-image of a powerful and influential group.

But today, the symbols and sources of power and influence have undergone a sea change. The Rajputs were landlords and land was the symbol and source of power. But the rural India is changing, and it is changing fast. Due to reservations in government jobs and in elected bodies, the members of the exploited, the deprived and the backward classes have come to wield administrative and economic power. They also have political influence. The enactment of tough laws to stop atrocities against them has also empowered the SCs and the STs. The old means and instruments for maintaining dominance have been rendered useless.

First Kayasthas and now Brahmins have overtaken the Rajputs, as far as presence in government jobs is concerned. Culturally, Brahmins were always at the top but Rajputs had a dominant position in social-religions functions. Now, Ambedkarism and Phulewad have come to dominate the social scene.

The Rajputs were known for exploiting their women. But with growing awareness and the rule of law, they are no longer able to lord over them.

The Rajputs take pleasure in being described as Bahubalis. They want to be feared. They are not comfortable with being looked down on. That is why, when Hindi films, up to the 1990s, depicted them as villains, exploiters and blood-thirsty men, they had no problems. But they objected to Dor, Water, Jodha-Akbar and now Rani Padmavati. They also object to showing Mirabai as someone who deserted her home.

The Rajputs have yet to recover from the shock of Phoolan Devi murdering members of their caste. Phoolan’s murder by Sher Singh Rana was the outcome of that feeling. And no wonder, after his release from jail, Rana has emerged as a darling of the Rajputs and there is hardly any function of the community in and around Saharanpur to which he is not invited. His hand is visible in almost all attacks on SCs in Saharanpur.

Director Anurag Kashyap brought out well this psychological problem of the Rajputs in his film Gulal (2009). You can see shades of Saharanpur, of General V.K. Singh, of Sher Singh Rana, in fact of Rajputs in general, in the film. Kashyap is now working on a film on Sher Singh Rana (as Rana himself told this writer).

Cultural challenge and message to society

Shabirpur has sent out a clear message to the country that the members of the Scheduled Castes want to live with social respect, equality, dignity and pride. Reservations in government jobs, legislative bodies, government contracts, and petrol pump and LPG dealerships, along with economic liberalization, better means of communication and transport and the media – all have given wing to their aspirations. Going by Karl Marx, this material prosperity is and will redefine their class. The class status of Dalits is changing all over the country, including in Uttar Pradesh. This has triggered a cultural change. The material and cultural changes are posing a stiff challenge to the established social hierarchy.

Therefore, it will be wrong to describe this violence as only casteist. The Rajputs did not unleash violence because of the caste factor. Violence can be termed casteist only if it has resulted from the sole reason that the opposing sides belong to different castes. In this context, India has been moving in a positive direction. Even amid the socio-cultural conflicts, we have been able to keep our democratic values intact. This was evident in the Saharanpur incident too. I will try to analyze this phenomenon further in my next article.

I had quoted Ambedkar at the beginning of this article to underline that India is completely lacking in liberty, equality and fraternity. Ambedkar says that for building a better society, we should not see the three values in isolation but as a union of trinity. If we have not been able to emerge as nation, it is because we have failed to pay heed to this prescription from Ambedkar.

Based in New Delhi, India, ForwardPress.in and Forward Press Books shed light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, literature, culture and politics. Next on the publication schedule is a book on Dr Ambedkar’s multifaceted personality. To book a copy in advance, contact The Marginalised Prakashan, IGNOU Road, Delhi. Mobile: +919968527911.

For more information on Forward Press Books, write to us: info@forwardmagazine.in