Unlike those who have made it in politics on the basis of family connections and wealth, CPI (ML)’s Raju Yadav is a social worker who has fought many a battle on the ground. A conversation with him also reveals how Dalitbahujans have become more aware and how, despite all odds, the youth are coming forward in politics.

Teacher’s attitude changed after knowing caste

“It is about those days when I was a Standard 7 student at the most famous school of Arrah (Bihar) – the Kshatriya High School. I was very good at studies and felt that my teachers were impressed with my academic acumen. But that was not true. One day, it was announced at the school assembly that all Dalit-OBC students would be awarded scholarships and that they should submit their names and their roll numbers. At that time, I used to write my name as Rajiv Ranjan Singh and my uncle Shivji Singh’s name was listed in the records as my father. That was because my father, Ramtavkaya Singh, was wanted by the police and there was a reward for Rs 25,000 on his head. Given that my surname was ‘Singh’ in the school records, my teachers thought that I was a Rajput. But they were surprised when I gave my name and roll number for the scholarship. My teacher Ramprasad Singh asked me why I had done so. I told him that I was a Yadav. That changed his attitude. He distanced himself from me. I learnt at my school itself to what extent caste pervades our society.”

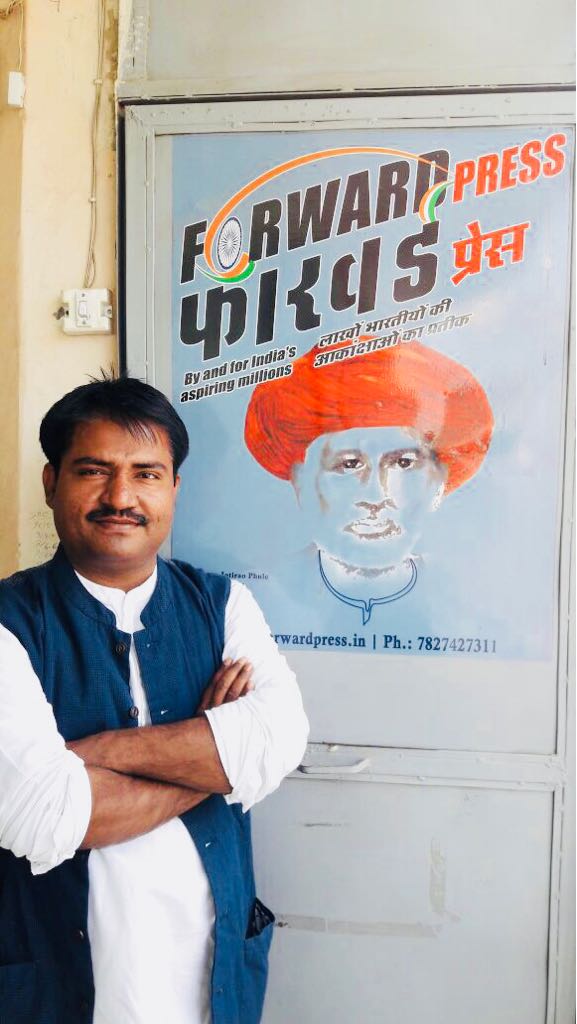

It was thus that Raju Yadav, a young Dalibahujan leader of Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), shared his childhood memories with FORWARD Press. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, he contested as a CPI (ML) candidate and gave a tough fight to Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidate R.K. Singh. Earlier in 2014, too, the party had fielded him and that, too, had ended in defeat. But these defeats have not deterred him. He says that the social realities he has seen while contesting elections motivates him to intensify his struggle.

His name is former CPI (ML) general secretary’s alias

Raju Yadav reveals how he got his name. He says: “Vinod Mishra, the former general secretary of the CPI (ML), had changed his name when he lived in Arrah during the days of the Left movement. People knew him as ‘Raju Neta’. I was born in 1982. My father named me Raju Yadav after Vinod Mishra, alias Raju.”

When asked how he got associated with the Left ideology, Raju Yadav said that it all began in the 1970s. “My father Ramatvakaya Singh was in the army and was posted at the Danapur Cantonment. My village, Gorpa, was just a kilometre away from Ekvari village in Bhojpur,” he says.

It may be recalled that the Left movement in central Bihar was launched from Ekvari in the 1970s by leaders like Jagdish Master and Ramnaresh Ram.

‘An OBC woman was burnt alive by feudals in my village’

According to Raju Yadav, at the time, Dalits and the Backwards were the victims of all sorts of atrocities at the hands of Bhumihars, the dominant castes. It was common for the dominant-caste men to forcibly harvest crops from their fields or to abduct their women. Resentment against the feudals was brewing. Amid all this, upper-caste people murdered his aunt. A few months later, a Yadav woman was burnt alive by setting her “gaithol” (a temporary hut for storing cow-dung cakes) ablaze. Thus, three persons were killed one after another. Meanwhile, the feudal lords brutally attacked his uncle, too.

Those days, Raju Yadav says, his father Ramtavkaya Singh was in Danapur. It was a while before he came to know about these incidents in the village but as soon he did, he quit his job and joined the Left movement. It was 1976, when for the first time in Central Bihar, feudal lords (nine of them) were eliminated. The agricultural labourers and the poor refused to do “begari” (unpaid labour) for the feudals. Raju Yadav was born in 1982. His father was active in the movement then. Several cases were also registered against him. After his death in 1990, his uncle raised him. The uncle never compromised on giving him a good education.

Raju said that initially he wanted to become a doctor. Hence, he studied biology up to Standard 12. But even before that, he had started participating in party activities. When he was in Standard 9, he led a protest against fee hike in the school. He became known as a student leader in the Arrah town. During his college days, he became associated with All India Students Association (AISA), the student wing of the CPI (ML), and went on to be the Bihar State Secretary. Apart from this, he also became the State Secretary of Inquilabi Navjwan Sabha, the youth wing of CPI (ML).

Despite his involvement in party work, he continued with his education. After completing his MA, he studied law.

Encountered social realities while contesting elections

What made him contest elections? He said that it was the decision of the party leadership. In 2010, the party for the first time fielded him from Barhara assembly constituency. He lost. Although he had to face defeat in 2014 Lok Sabha elections, he polled nearly one lakh votes. He was again fielded by the party in 2019 general elections. This time, he was backed by the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and got more than four lakh votes. Still, he came only second to the BJP candidate R.K. Singh.

Raju Yadav says that it was a different experience for him to contest elections. According to him, when you work for a party, you only interact with the people whose ideological leanings are the same as yours. But an election campaign gives you the opportunity to understand society. He says the OBCs are leading a miserable life in Bihar. “When you go amidst the people you will know how a Yadav family lives with his cattle in a small hut. You will meet Kurmis and Kushwahas who do not have an inch of land. They are farm labourers. You will be surprised to know that about 80 per cent of the OBC population in Bihar is in the same condition as the Dalits. But you will know all this only when you go to the villages,” he says.

On how the Dalitbahujan youth can have a bigger say in politics, Raju Yadav quotes Dr Ambedkar and says: “The Dalitbahujans should have an equal right to this key [to power]. There is nothing wrong in joining politics provided your objective is to contribute to the building of a society where everyone gets equal opportunities and respect.”

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Goldy/Anil)