While being the mirror of society, Baburao Bagul’s literary creations were rebel acts that aimed at dethroning the brahmanical forces. He broke new ground in Marathi literature by evolving a “Dalit consciousness”.

His characters not only question the inhumane caste-based hierarchy but destroy its very base. They are angry, they dissent, they revolt. They are subjected to unbearable sufferings, but they are not resigned to their situation. They fight ferociously to assert their self-respect and dignity. His stories do not consist of “saviours”; the downtrodden themselves are the heroes who rise in rage against the system that is the reason behind their degradation. Hence, Masthur, the protagonist in one of Bagul’s stories, says, “When was I beaten by them? It was Manu who thrashed me” (Bagul, 2018).

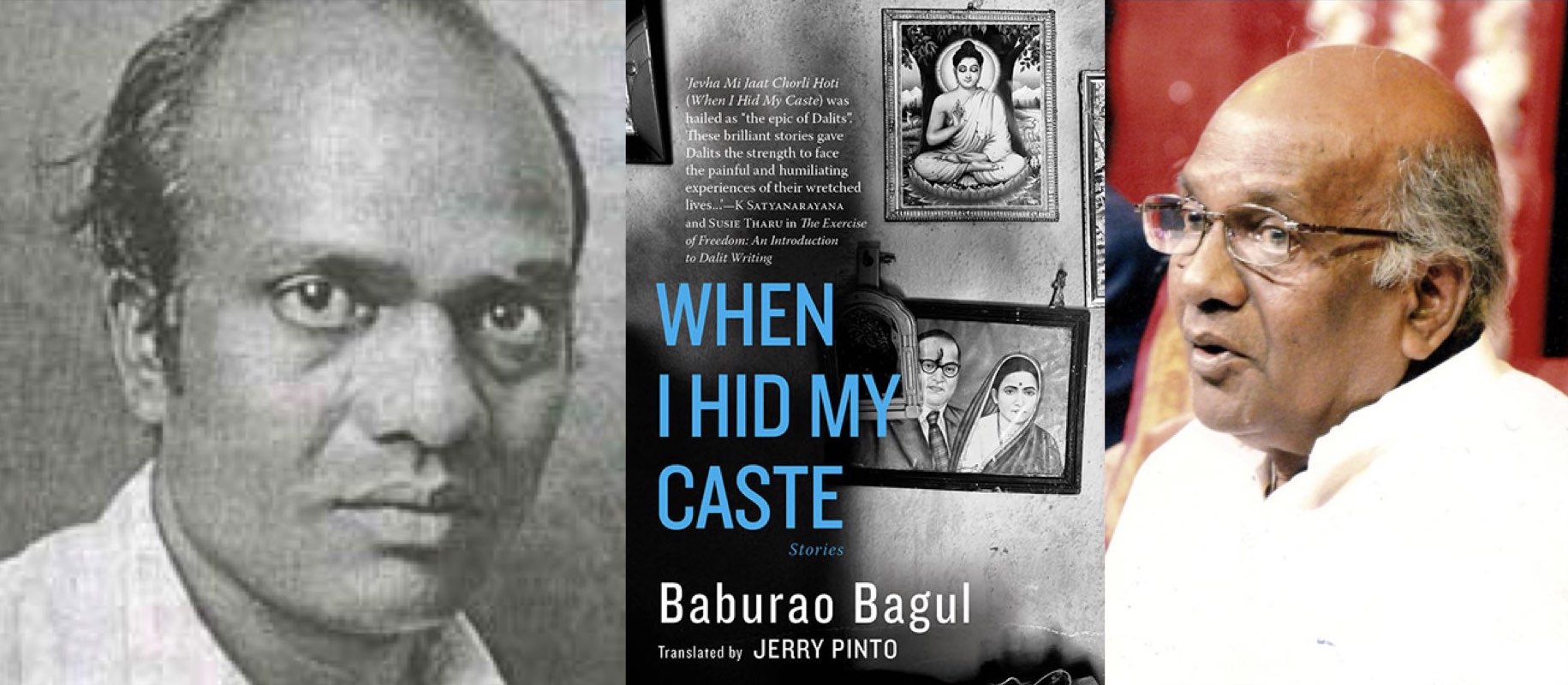

Baburao Bagul started writing in 1952. His groundbreaking works include his first collection of short stories, Jevha Mi Jat Chorli Hoti (When I Hid My Caste), published in 1963. According to K. Satyanarayana and Susie Tharu (2013), this first book by Bagul was hailed as “the epic of Dalits”. The collection opened up new formal and thematic ground and gave Dalit literary thinking a huge momentum. He went on to publish Maran Swast Hot Ahe (Death is Getting Cheaper) in 1969 and Sud (Revenge) in 1970.

Out of the grand collection of short stories that he wrote, “Revolt” and “When I Hid My Caste” brings out the protest against, to use Ambedkar’s term, the “division of labourers”. The conversation between Jai and his father in “Revolt” tears apart this division:

“‘Where is it written that a Bhangi’s son must become a Bhangi?’, asks Jai.

‘In our poverty. In our dharma. In our country’, replies his father.

Jai doesn’t give in. He goes on to ask, ‘What dharma? If it breaks a person and turns him into an animal, is that Dharma? In this country that invests greater significance in a stone than in a human being? I will not heed such a dharma. If it has given us only this poverty, this deprivation, then it behoves us to reject it’” (Bagul, 1999: 29-37).

When Kashinath in “When I Hid My Caste” asserts his defiance against the birth-based occupation given to him, he shouts in rage, “I am a Mahar but that doesn’t mean I’m going to clean human shit and piss from the walls.”

Both of them envisage a future in which they have gotten rid of their pain. They have a strong ambition to break away from the clutches of caste through education. Ambedkar’s clarion call to “Educate, Agitate, Organize” echoes when Jai argues with his father saying, “Just for this I should become a Bhangi? Give up my education to clear up the dirt of the village? Carry filth on my head? If you wanted me to do that kind of work, why did you have me educated? Why did you let them light these lamps of independence, knowledge and humanity inside my mind?”

Similarly Kashinath’s dream of liberation lies in becoming a lawyer. In a conversation with the protagonist of the story, he remarks, “Masthur, I’m going to quit this job. I’m going to Mumbai. I’ll take what work I can get. I’ll finish my SSC. I’ll go to college. I’ll become a lawyer … This life, this terrible life.”

These two stories are set in contrasting locales but have glaring similarities. “Revolt” has a rural setting while “When I Hid My Caste” unfolds in modern urban space. Caste travels with people like a shadow – it is rigid enough with respect to one’s position in the hereditary social hierarchy but on the other hand it is fluid enough to cross borders as well. The glitters of city life are not “casteless”. In fact, the skyscrapers which stand proudly in the cities are symbols of caste-based segregation.

In “When I Hid My Caste” , the landlord Ramcharan, while renting his room to Masthur, says, “When we meet a stranger, we always ask him his caste. This is the way in our country.” Another man adds, “Brother, we can eat mud with a caste brother, but one shouldn’t attend a feast with someone of lower caste.”

Ramcharan, who initially admires Masthur for being a poet, unleashes violence upon knowing his caste. He beats him not for hiding the truth. Masthur invites his wrath for daring to break the brahmanical monopolization over knowledge. He is subjected to cruelty for writing and reading, something which the “lower castes” were barred from doing for ages. This incident exposes the irony of a society which cries hoarse about so-called “merit”. Masthur’s talent was discarded because of his caste.

DALIT LITERATURE AND BAGUL’S CONTRIBUTION

Dalit Literature is not simply a literary trend or formal development. It is a social movement taking on injustice and is driven by the hope of freedom. Baburao Bagul argued that “the established literature of India is Hindu literature” and that the lowest castes are excluded from Indian literature because of its Hindu character. He elaborates: “Writers who have internalized the Hindu value-structure find it impossible to accept heroes, themes and thoughts derived from the philosophies of Phule and Ambedkar” (Dangle, 1992). Bagul makes a radical change in this regard. The peripheries are his plot. The defiant heroes of the margins are well represented in “Gangster” and “Streetwalker”.

In an essay he wrote for the 1969 Diwali issue of Marathwada, Bagul asserts:

“Dalit literature believes that looking for the meaning of life in social debates, philosophy or political manifestoes would make it monochromatic. The meaning of life is to be found in Nature. Man is the very embodiment of Nature. His desires, passions, emotions are the sun, moon, rain, shine, storms and gales of Nature. When these natural desires and emotions were crushed as the shad-ripu or the six perverse passions of human life, religion and gods became immortal and life, which once sang hymns to Usha, the Goddess of Dawn, was incarcerated in the dark. But now we herald the coming of tempests, wildfires and light; of varied paths and triumphant chariots. The ages will come and go like birds alighting on trees, and joys will abound.”

Hence, Bagul sees Dalit Literature not as mere contestations in the discourse of politics and philosophy, because this one track, all-consuming approach would deprive an individual of his creativity and passion. For him, the meaning of literature is to be found in a person’s emotions and desires. But when these were discarded as perverse, god and religion gained supremacy to dictate man. Bagul personifies tempests, wilderness and light, which is revolutionary, marking a discontinuity from the period when man’s emotions were supposed to revolve around the dictates of religion.

The Dalit Sahitya Sansad was established under the leadership of Baburao Bagul. Daya Pawar and Arjun Dangle held the position of general secretary of Dalit Sahitya Parishad (Pawar, 2019).

Yogesh Maitreya (2018A) argues that Baburao Bagul, Sharad Patil and Sharankumar Limbale have helped construct a theory of Dalit Literature. Bagul’s 1981 work, Dalit Sahitya: Aajche Krantividnyan, is a ground-breaking work in this construction in which Dalit experience is reiterated as part of Dalit Literature.

R. Kimbhaune (1999) explains why Bagul’s work stands out. He says it is because of his originality and achievement both in terms of subject matter and use of language. Bagul’s stories are packed with judiciously chosen realistic details from the lives of the downtrodden castes, the destitute, the depraved and criminals. The women characters in his stories depict a dignified celebration of Indian women.

In her foreword to When I Hid My Caste, Shanta Gokhale (2018) notes, “He knocked readers off their feet by the sheer elemental force of his stories. But, more importantly, he liberated younger Dalit writers from the shackles of literary Marathi. They were now free to write in their own dialects. If readers, weaned on the preponderantly romantic literature of upper-caste Marathi writers, found these new voices difficult to stomach, so be it.”

Baburao Bagul has left a legacy for poets who engage with brutal realities of India’s casteist society. His vision gives direction and hope to the present-day poets. Yogesh Maitreya (2018B) says, “While the most striking aspect of Baburao Bagul’s stories is his ability to provide words for the pain that Dalits have to suffer in their everyday life, he does not stop there. His writings possess a charisma that makes a reader feel what most literary narratives lack in India – he encourages us to develop a perspective that is humane amidst an inhumane society of caste(s).”

BAGUL’S WRITING AS A SOCIAL REVOLUTION

Again, in her foreword to When I Hid My Caste, Gokhale (2018) notes that playwright Datta Bhagat asserts the political importance of Bagul’s work. According to Gokhale, Bhagat argues that Bagul established Dalit Literature as a movement which is the reflection of the social movement led by Jotirao Phule, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Gopal Ganesh Agarkar demanding freedom, justice and equality.

Bagul did a considerable amount of public speaking. According to Eleanor Zelliot (1982), his comments evoked pungent emotions and the mood of Dalit Literature. She quotes Bagul: “Even if Manu has been thrown into darkness, he has not died. He is living today in books, in holy scriptures, in temple after temple. He lives in mind after mind. The structure of the society that he created is what we have today. He is so great that society’s arrangements are under his control. And only his loving people are at the centre of power. So in India at this time there are two worlds, two powers, two life traditions and two scriptures. He who wants victory, he who wants influence must take a role in determining the future.”

Bagul was a rebel and a visionary. His vision was based on his realization of the root cause of the degradation of Dalits. His attack on Manu as part of his protest against the caste system and untouchability distinguished him from other writers who, even while talking about miseries and human pain, never questioned the root cause. Bagul’s explanation of how Manu still rules this society is an important argument that needs to be reiterated to “his loving people” who are quick to dismiss puranas and dharmashastras and the casteism that they theorize and uphold as things of the past.

Baburao Bagul established a discourse in which Dalit Literature does not mean sorrowful accounts alone. It is rather a revolutionary form of assertion, a part of the movement aiming to annihilate caste; it is a celebration of dignity of the hitherto marginalized. In a society in which people are unwilling to see an aspiring Dalit, Bagul’s work should be read again and again, louder than ever.

REFERENCES

Bagul, Baburao. (1999). Rebellion. [Translation: Jayant Deshpande]. Indian Literature 43/ 6 (194): 29-37. Accessed on July 6, 2020 from www.jstor.org/stable/23342843

________. (2018). When I Hid My Caste. [Translation: Jerry Pinto]. Mumbai: Speaking Tiger Publication.

Dangle, Arjun. (Ed.) (1992). Poisoned Bread: Translations from Modern Marathi Dalit Literature. Hyderabad: Orient Longman.

Gokhale, Shanta. (2018). Foreword. In “When I Hid My Caste”. Mumbai: Speaking Tiger Publication.

Kimbahune, R.S. (1999). A Note on Contemporary Short Story in Marathi. Indian Literature 43/6 (194): 17-23. Accessed on July 6, 2020 from www.jstor.org/stable/23342841

Maitreya, Yogesh. (2018A). Towards a Theory of Dalit Literature. Economic and Political Weekly, 53/51.

________. (2018B). When I Hid My Caste: Baburao Bagul’s short stories were steeped in his ideologically vibrant youth. Scroll.in (2018), Accessed on 1 July 2020 from https://scroll.in/article/892521/when-i-hid-my-caste-baburao-baguls-short-stories-were-steeped-in-his-ideologically-vibrant-youth

Pawar, J.V. (2019). The History of Marathi Literature. Forward Press (2019), Accessed on July 1 2020 from https://www.forwardpress.in/2019/04/the-history-of-marathi-ambedkarite-literature/

Satyanarayan, K. and Susie Tharu (Eds.) (2013). The Exercise of Freedom : An Introduction to Dalit Writing. New Delhi: Navayana Publishing.

Zelliot, Eleanor. (1982). A Note on Baburao Bagul. Journal of South Asian Literature 17/1: 56. Accessed on July 6, 2020 from www.jstor.org/stable/40874005

Editing: Goldy/Anil

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History