The Supreme Court’s judgement upholding the validity of the legislation providing a 10 per cent quota to the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) has triggered a nationwide debate on reservations.

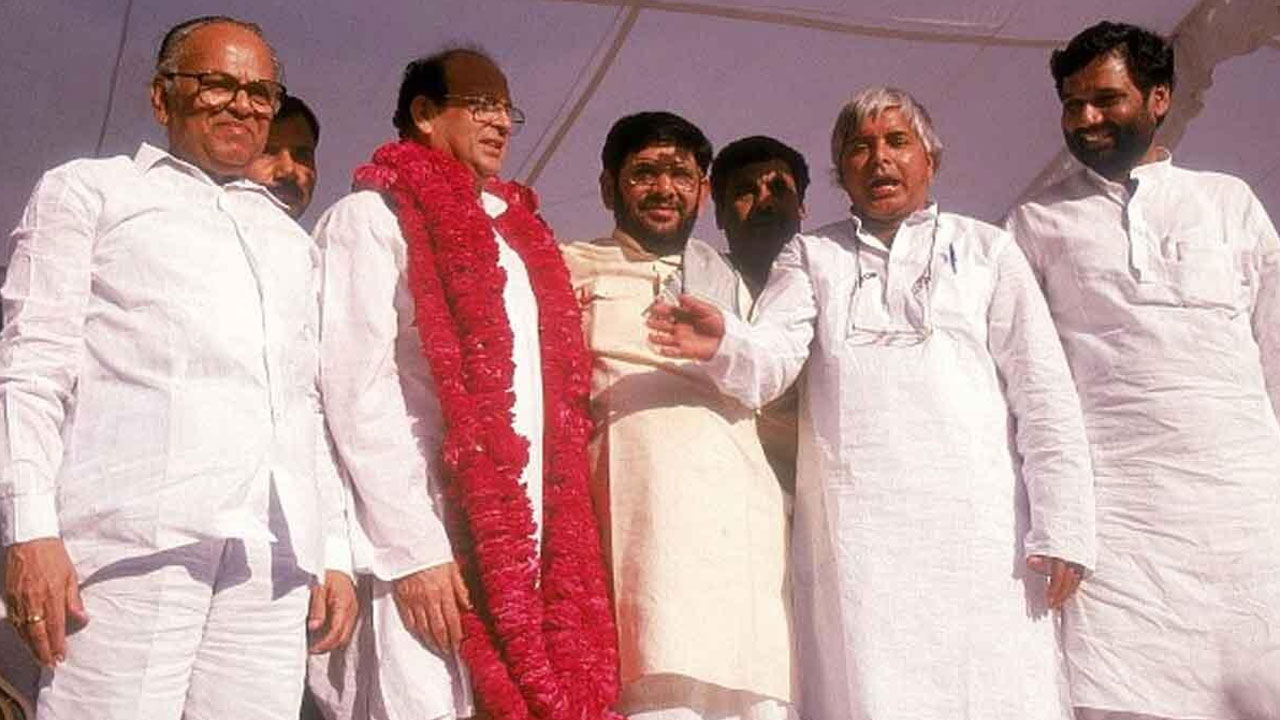

With the Constitution of independent India coming into force on 26 January 1950, Dalits (Scheduled Castes) and Adivasis (Scheduled Tribes) got 15 per cent and 7.5 per cent reservations, respectively. This reservation applied to services under the State, institutions of higher learning and legislative bodies. But reservations for OBCs hung fire for decades. It was about 40 years later, on 7 August 1990, that the government led by prime minister Vishwanath Pratap Singh, announced 27 per cent reservations for the OBCs in State services on the basis of the recommendations of the Mandal Commission.

This decision was bitterly opposed through both violent and non-violent means by the upper castes. The matter went to the Supreme Court. A nine-judge Constitution Bench of the apex court upheld OBC reservations but inserted the “creamy-layer” rider. At the time, youth with annual family income of more than Rs one lakh per annum were placed in the category of “creamy layer”, thus depriving them of reservations. That cap is pegged at Rs 8.5 lakh per annum now. That was how economic criterion slithered into the reservation regime, even though it was against the concept of reservations, as envisaged in the Constitution. The OBCs have been described as “socially and educationally backward classes of citizens” in the Constitution.

The Mandal Commission, in its report, had said that the key benefit that would accrue from reservations was not that an egalitarian society would emerge from among the OBCs but that it would end the monopoly of the upper castes on government services. Be that as it may, the OBCs getting 27 per cent reservation and the Mandal resurgence led to reservations and social justice becoming central to the coming together of the Dalits, Adivasis and OBCs. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) realized that the rise of the 52 per cent OBCs would adversely impact the privileges and the hegemony of the savarnas and thus deal a blow to Brahmanism. It branded the Mandal-triggered resurgence as “Shudra Revolution” and underlined the need to treat it as a challenge that must be overcome. A counter-revolution was initiated, aiming at pushing the OBCs back to where they were in socio-economic and political terms and ultimately establishing a Hindu Rashtra by way of suppressing the issue of caste.

The government moved the 103rd Constitution Amendment Bill in the Lok Sabha on 8 January 2019 and, with lightning speed, implemented the 10 per cent EWS quota on 14 January 2019. The reservation for the EWS marks the completion of the first stage of the counter-revolution. Work has now begun on the second stage, which will have deeper sociopolitical implications.

It should be noted that no commission was appointed to evaluate the legitimacy of EWS reservation. Petitions challenging it were filed in different courts, but even while the court’s verdict was awaited, EWS reservation remained in force. Amid the slogans of “Save the Constitution”, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court, on 7 November 2022, upheld the validity of the 103rd Constitution Amendment.

The question that arises from this judgement is: Hasn’t the Supreme Court played the role of a patron of Savarna privileges and hegemony rather than standing for the Constitution?

The fact is that this amendment is a part of the RSS-BJP’s counter-revolution, aimed at dismantling the basic structure of the Constitution and imposing Manu’s code on the country, thus furthering the Hindu-Rashtra agenda. The amendment seeks to expunge social justice from the basic tenets of the Constitution, and guarantees the perpetuation of savarna hegemony and privileges.

Earlier too, the Supreme Court has been under fire for its attitude towards Dalits, Adivasis and OBCs, especially vis-à-vis reservations. But even the anti-BJP political parties have not been forcefully demanding unwavering adherence to the Constitution. The lone exception is DMK leader and Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin. He has flayed EWS quota without any ifs and buts and has refused to implement it in his state. He has described the Supreme Court judgement as a jolt to the struggle for social justice. The reactions of others range from being welcoming to being in agreement to silence. As for the Congress, it is competing with the BJP to claim credit for EWS reservation. The non-political opponents of the BJP are also merely murmuring their disagreement. Besides DMK, only the CPI (ML) has taken a logical and clear political stand on the issue. The Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) is on the back foot. The crowds of the Bahujan movement that claim to be warriors against Brahmanism are also quiet, passive.

In fact, Narendra Modi coming to power in 2014 was in itself a milestone in the RSS-BJP’s counter-revolution. Now, even the Constitution and democracy are under threat. The Congress, regional parties, social-justice parties, Left parties as well as democratic forces of different hues have been talking of saving the Constitution. But they have different ideas and different perspectives on the issue at hand.

When the Narendra Modi government introduced the 103rd Constitution (Amendment) Bill, just before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the opposition in both the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha did not oppose it vociferously. Only three members had cast their votes against the amendment in the Lok Sabha and just seven in the Rajya Sabha. There was little protest on the streets either.

It is clear that social justice is missing from the “Save the Constitution” slogan of the entire spectrum of political parties. The stream of social justice is bent towards savarnas. The political standing of Dalits, Adivasis and OBCs is diminishing. The Mandal resurgence had given a pro-Dalit, pro-Adivasi and pro-OBC hue to politics. But now, it too has acquired a pro-savarna character. Hindutva has become the fulcrum of politics. Can the opposition really save the Constitution by becoming a handmaiden to the politics of Hindutva?

After Narendra Modi’s return to power in 2019 with a historic mandate, many commentators predicted the end of Mandal politics. It was said that Modi had the capacity to break the stranglehold of caste on politics. Modi himself remarked, “There will be only two castes in the country from now on and the country will be focused on these two castes. In the 21st century, in India, one caste is the poor, and the other caste is that of those who contribute to freeing the country from poverty.” This new definition of “caste”, in fact, negates the historicity of caste. Negating the historicity of caste means erasing the very basis of social justice. The end of the discourse on caste will mark the end of the concept of social justice.

Modi’s new definition of caste also assails the concept of class struggle and attempts to obliterate the struggle for economic equality. In fact, Modi has been, time and again, attacking caste politics and emphasizing development. Only recently, the RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat said, “The caste system belongs in the past and should be forgotten.”

The implications of the statements of Modi and Bhagwat are clear. The consciousness of sociopolitical justice and anti-capitalism are impediments in the path of Hindutva politics. Burying the question of caste and the concept of class struggle is imperative for the growth of this brand of politics.

By means of EWS reservations, not only have Savarna privileges and dominance been secured over the long term, the ideology and politics of social justice have come under massive attack. Established political ideologies have been destroyed. The distinction between social and economic justice has been blurred. The definitions of social justice and economic justice have been changed. The contents of various policies and programmes designed to resolve specific problems have been tinkered with and presented in the mould of Hindutva. The oppressed identities opposed to Hindutva have been severely damaged. Social justice or the concept of reservations, which form the basis of these identities, has been battered and the foundations of social justice have been attacked. Consequently, Mandal-Bahujan politics is faced with an existential crisis.

EWS reservation is, fundamentally, savarna reservation. There could have been no basis other than economic status for providing reservation to savarnas. Only by converting reservations into a tool for poverty alleviation, can it be used to guarantee the privileges and hegemony of the Savarnas. By presenting the reservation regime as a tool for economic welfare and poverty alleviation, the essence of the concept of reservations has been changed. Social justice, which informs the basic structure of the Constitution, has been discarded, even in the face of the truth that reservation can never be a tool for poverty alleviation or economic welfare. Curbing corporate loot and changing economic policies is the only way to deal with economic problems like poverty.

However, reservations have been presented as an answer to economic problems. Reservations as a solution to economic problems becoming statutory will now strengthen the notion that these are a poverty alleviation programme. When this wrong concept takes root among the SCs, STs and OBCs, the struggle for social justice will be weakened. This will blunt both the social-justice consciousness and class consciousness. This will reduce the citizens to beggars who have no rights, paving the way for turning them into “beneficiaries” of different schemes. Those fighting socio-economic inequalities are faced with a challenge. Whether it is the forces fighting for social justice or economic justice, Left movements or Bahujan movements, ignoring EWS reservations will prove fatal. They will have to take to the streets to oppose it. Also, the issues of socio-economic justice will have to be addressed in their entirety. The Left and Bahujan movements cannot hope to take on this challenge in isolation.

It is ironic that amid the efforts to change the Constitution and consign the concept of social justice to the dustbin of history, some are still happy that the judgement has made it possible to breach the 50 per cent cap on reservations. In Bihar, the RJD and the Janata Dal United (JDU), instead of opposing Savarna reservations, are talking about a caste census and reservation for various communities in proportion to their share in the population. The Hemant Soren-led Government of Jharkhand has already breached the 50 per cent cap. Anti-BJP political formations are raising issues like the caste census, increasing the OBC quota and reservations in the private sector. Quotas for SCs, STs and OBCs from the top to the bottom in the judiciary have also become a topic of discussion. This, of course, is essential for changing the character of the judiciary. In the short run, it may seem as if the struggle for social justice is moving forward and may get a boost. But it is also possible that the progress of the struggle may become more difficult and complex. That is because social justice has been uprooted from the Constitution, and the very source of strength of the social-justice movement has been deeply dented.

Only the future will tell whether fighting shy of opposing EWS reservations would open new doors for the struggle for social justice, or push it into a blind alley. Would EWS reservations prove a milestone for the flag-bearers of Hindu Rashtra, Manu’s code and Brahminocracy? Let us not look at this issue from the narrow perspective of electoral defeats and victories.

(Translated from the Hindi original by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)