What happens when an Ambedkarite with a keen interest in history gets to meet someone who has not only heard Dr B.R. Ambedkar speaking but has also worked alongside him? Over the past 30 years, I have met many such people and every time I have felt extremely proud and blessed. Talking with such individuals is a real pleasure and whenever I get such an opportunity, I try to preserve whatever they tell me.

On 7 December 2022, I visited Kartar Singh Sulekh at his residence in Chandigarh. He was the general secretary of the Punjab unit of the Scheduled Castes Federation (SCF) founded by Ambedkar, and had met Ambedkar on many occasions. On 25 November 1949, along with Seth Kishan Das, president of the Punjab unit of SCF, Sulekh was seated in the visitor’s gallery when Ambedkar delivered his historic speech in the Constituent Assembly. Recalling those moments, he says “When Babasaheb was speaking, the House was all ears. He received a standing ovation after the long speech. The members thumped their desks and clapped to express their admiration. Jawaharlal Nehru shook hands with him. Other members, too, congratulated and embraced him.”

Kartar Chand Sulekh was born to Beeru Ram and Dani at a place called Banga in Nawanshahr district of Punjab on 20 July 1927. His father passed away at the age of 65. At the time, Sulekh was a Standard 9 student. His father was a traditional doctor who treated those bitten by snakes and other venomous creatures. He was also a folk singer.

Reminiscing about his first meeting with Babasaheb, Sulekh said that he had travelled to Delhi along with Seth Kishan Das to meet him. This was just days before Gandhiji was assassinated. They had plans to launch an Urdu newspaper “Ujjala” to promote and protect the interests of the Dalits of Punjab and it was in that connection that they wanted to meet Babasaheb. Gandhiji, as we all know, was assassinated by Hindu Mahasabha member Nathuram Godse on 30 January 1948.

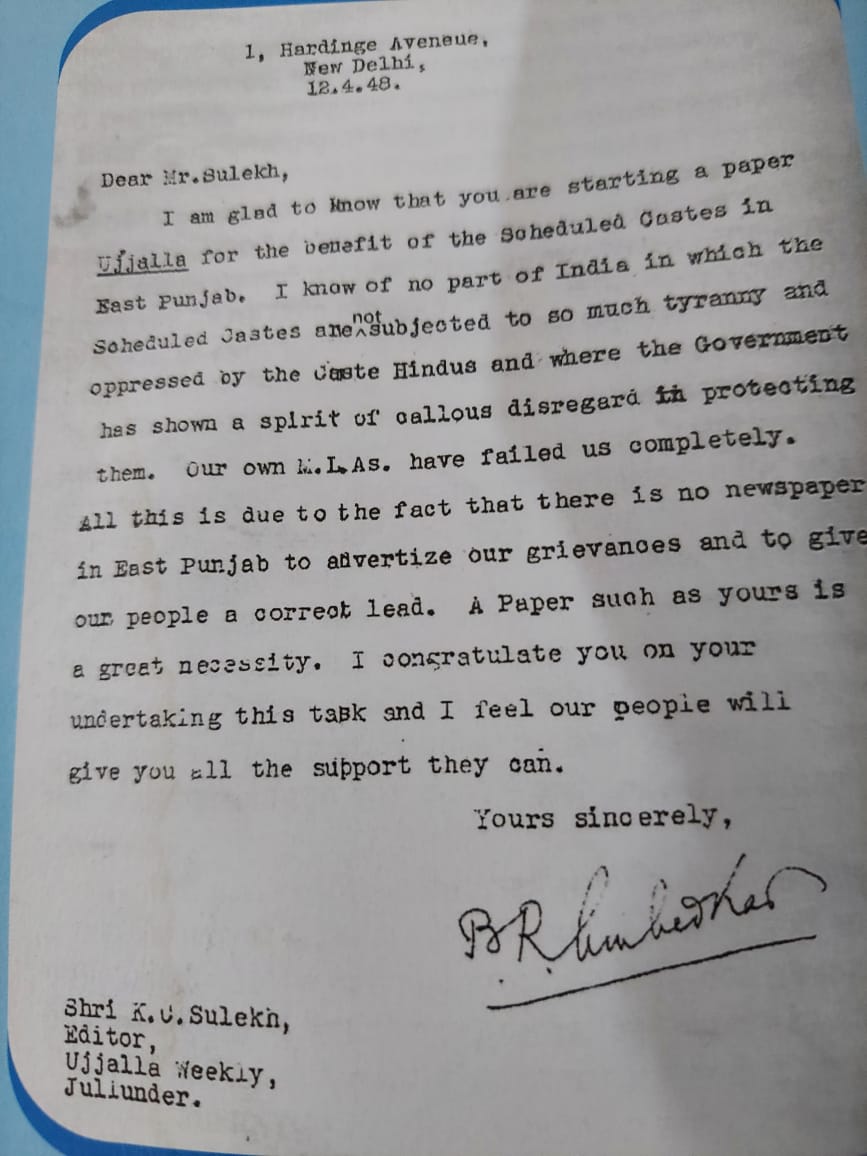

Babasaheb had sent Sulekh a message on the occasion of the launch of the newspaper. Sulekh has carefully preserved Ambedkar’s letter to date. Dated 12 April 1948, Ambedkar wrote the letter from his New Delhi residence – 1, Hardinge Avenue. It read like this:

Dear Shri Sulekh,

I am glad to know that you are starting a paper, ‘Ujjalla’, for the benefit of the Scheduled Castes in East Punjab. I know of no part of India in which the Scheduled Castes are not subjected to so much tyranny and oppressed by the Caste Hindus and where the government has shown a spirit of callous disregard in protecting them. Our own MLAs have failed us completely.

All this is due to the fact that there is no newspaper in East Punjab to advertise our grievances and to give our people a correct lead. A paper such as yours is a great necessity. I congratulate you on your undertaking this task and I feel our people will give you all the support they can.

Earlier, Sulekh had translated Ambedkar’s famous book Mr Gandhi and Emancipation of the Untouchables into Urdu. This was perhaps the first translation of any of Ambedkar’s works.

How Sulekh got an opportunity to meet Ambedkar is a story in itself. Seth Kishan Das, who would later become the president of the Punjab unit of SCF, was elected to the Punjab assembly in 1937 and remained its member till 1946. There were no seats reserved in Punjab for the Scheduled Castes under the Communal Award of 1932. However, after the Poona Pact was signed, Punjab got nine such seats. One of these was Boota Mandi near Jalandhar, from where Kishan Das contested with a Unionist Party ticket and won. In 1942, Kishan Das met Ambedkar at a convention of the SCF in Nagpur and was so impressed that he founded the Punjab unit.

At the time, Sulekh was a student of Doaba College, Jalandhar. Impressed with Ambedkar, he started working for the SCF. Sometime later, Seth Kishan Das appointed him general secretary, and then he never looked back. Along with Seth Kishan Das, Sulekh travelled extensively in Punjab and in other parts of the country to take part in different events. That was how Sulekh got the opportunity to hear Ambedkar’s speech at the last sitting of the Constituent Assembly on 25 November 1949.

In the subsequent years, Sulekh heard and saw Ambedkar from close quarters on many occasions. After the promulgation of the Constitution, Ambedkar, at the request of the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, immersed himself in drafting the Hindu Code Bill. Ambedkar believed that the Hindu Code Bill would play a historic role in the social transformation of India. The new Constitution was in place but the agenda of social reform was still unfulfilled. Ambedkar was aware that many senior Congress leaders, including Dr Rajendra Prasad and Sardar Patel, were opposed to the Bill but he was confident that Prime Minister Nehru would ensure its passage in Parliament. But that Bill did not get Parliament’s nod and was truncated. This hurt Ambedkar deeply.

According to Sulekh, Ambedkar was furious, for he had worked hard on the proposed legislation. Rajendra Prasad, K.M. Munshi, Anant Swami Iyengar and several others had ganged up against it and Nehru was forced to back down.

In April 1951, Ambedkar quit the Union Cabinet over differences with the government on the Hindu Code Bill and other issues. He wanted to tell the Parliament why he felt compelled to resign, but for many days he was not allowed to do so. Ultimately, on 10 October 1951, he made a statement in the Parliament. Sulekh and Seth Kishan Das were again present in the visitor’s gallery. Soon, the General Elections of 1951-52 were announced. The SCF wanted Ambekdar to visit Punjab, where he had a large following.

Sulekh narrates that Ambedkar reached Amritsar by air on 27 October 1951 and travelled from there to Jalandhar by road. On the way, he was welcomed warmly by the people at many places. He addressed two public meetings in Jalandhar – one at Aabadi, where an Ambedkar Bhavan has come up now, and the other at DAV College. At the time, Sulekh was a student as well as an activist. He oversaw the publication of ‘Ujjala’ and had already translated many of Ambedkar’s articles into Urdu for the newspaper. Now he was given the charge of organizing the historic rally at Jalandhar.

Sulekh recalls that a rousing welcome was given to Ambedkar in Jalandhar. Ambedkar addressed the rally at around 4 pm. He spoke in a language that the common people could easily understand. His style was akin to that of an elder counselling the younger members of the family. Ambedkar was accompanied by his wife Savita Ambedkar, Seth Kishan Das, R.C. Pal (secretary, SCF) and others. So popular was Ambedkar that people were dying to come close to him, to touch him. He spoke for about an hour and a half. The audience heard him with rapt attention. Only his voice resonated in the air.

At the public meeting, Ambedkar talked about the atrocities being committed against the Dalits in Pakistan and flayed the then government, for he believed that it was not acting with adequate alacrity in the matter. Dalits had suffered the most due to Partition. The situation in Pakistan was precarious and there were reports that the Dalits who wanted to leave Pakistan and go to India were not being allowed to do so, because the Pakistani leaders feared that if all the Dalits left for India, there would be no left to do the cleaning work there.

After the Partition, says Sulekh, the Dalits were in dire straits in both Bengal and Punjab. They were being forcibly converted and their homes were being looted. Ambedkar urged Nehru to intervene without delay. It was at his insistence that the jawans of the Mahar Regiment were dispatched to the border areas to help the civilians. They worked hard with all sincerity for a year and helped the Dalits, especially the Mazhabis, to migrate to India. The Mahar Regiment had been disbanded in 1946 but three battalions of the regiment were operational as the Punjab Border Force. Ambedkar knew that for the elite, whether Hindu or Muslim, Dalits were mere servants and the leaders of the newly created Pakistan were unwilling to give them equal rights.

Sulekh says a horrific politics-power nexus lured many Dalits away. Mota Singh Layalpuri, the general secretary of SCF, joined the Akali Dal and Sulekh replaced him. In the 1952 general elections, Sulekh was asked to contest from one of the eight reserved seats as an SCF candidate. Sulekh was not old enough to contest the elections and some of his friends suggested that he should fake his age. But he refused to do so. The SCF’s performance in the elections was dismal and that had a great impact on the morale of its supporters. Sulekh holds the joint electorate system responsible for the crushing defeat of the Federation.

Sulekh went on to marry and had a son. He needed a job, but he never mentioned it to Ambedkar. He feared that Ambedkar might think that he had joined the Scheduled Castes Federation just to get a job. Be that as it may, he first got a job in Delhi. Then he moved back to Punjab, where he joined the Excise Department of the Punjab government on 14 October 1952 and worked there until 31 July 1985.

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)