Besides Khadi Boli (the Sanskritized modern version of Hindi), the Hindi language can be taken to include all the sub-languages, dialects and folk tongues spoken and understood in the Hindi belt. Sanskrit also belongs to the same stable, as it shares a common script with Hindi. It is often believed that languages and scripts are the scholars’ domain. This is not true. “Bhasha”, the Hindi word for “language”, has its root in the Sanskrit word “bhāṣā”, which means speaking. Thus, language is what the people spoke. The literature of different languages was conserved for centuries in oral form. When we talk of the role of the backward castes and Dalits in the development of Hindi literature and language, we mean these languages and literature that was preserved but was scattered across various folk languages, from which standardized language and literature was born. In this respect, the contribution of the Adivasis also can’t be ignored.

Urdu, Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Prakrit, Pali, Apabhramsa (languages spoken in north India before the rise of modern languages) and folk tongues – all have contributed to the development of Hindi. The Devanagari script has evolved from pictorial, Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. All these aspects will have to be taken into consideration while dwelling on the topic.

Ruling dynasties, Varna and religion in ancient India

The Harappan (or the Indus Valley) civilization is the oldest civilization of India. “It is believed to have lasted from 3000 BCE to 1500 BCE. The Harappans knew reading and writing and their script, which is yet to be deciphered, was pictorial and cuneiform. This was followed by the Vedic or the Brahmin civilization which lasted from 1500 to 500 BCE.”[1] The year of Alexander’s invasion – 326 BCE – during the regime of Nanda king Dhana Nanda, is used as the base to calculate the period of the rule of ancient Indian ruling clans. The Indian texts do mention the number of years for which a particular king ruled but say nothing about which year the rule began and which year it ended. That was so because no calendar was in use. The Aryan or the Brahmin civilization spread over Sapta Sindhu (modern Punjab, Kashmir, Pakistan and so on) and the Uttarapath or the Aryavarta (land of the Aryans). The history of the ruling clans and the republics in India is available from around 600 BCE onwards. It was in this period that Mahavir Jain and Gautam Buddha founded their religions. With time, Buddhism reached many parts of the world. The Magadha Empire lasted from 544 BCE to 647 CE. The dynasties that ruled the empire included Shishunaga, Nanda, Maurya, Shung, Kanva, Gupta, Shaka, Kushana and Vardhan. Among them, barring the Guptas, all were either Jains or Buddhists. Harshavardhana (647-590 CE) was the last Buddhist ruler. It was around this time that scriptures began to be written.

In ancient India, Buddhist kings were usually not Brahmins or Kshatriyas. Of the rulers listed above, barring Harshavardhana, all were non-Brahmins and non-Kshatriyas. Romila Thapar writes that most of the leading ruling clans of north India that came after the Nandas were non-Kshatriyas and this continued till the advent of the Rajputs about 1,000 years later[2]. About the Nanda clan, Thapar says, they belonged to a lowly class, yet they became the first among the non-Kshatriya ruling clans when they snatched the throne from the Shishunag clan. According to some sources, Mahapadma Nanda, the founder of the Nanda ruling clan, was the son of a Shudra mother. Other sources claim that he was the son of a barber and a prostitute[3]. The Puranas describe Mahapadma Nanda as a Chakravarti Samrat (a universal monarch), Ekraat (sole sovereign) and sarva-kshatrantaka (the destroyer of all Kshatriyas). Acharya Panini, the celebrated scholar of Sanskrit grammar, was a friend and a courtier of Mahapadma Nanda. He wrote his famous work, Ashtadhyayai, during his stint in the Nanda palace. Similarly, other scholars like Varsh, Upvarsh and Varruchi Katyayan also graced the court of Mahapadma Nanda. Shaktay and Sthubhadra were Jain amatyas (ministers) and scholars in the court of Dhana Nanda. Most of them were influenced by Jain and Buddhist beliefs and were atheists.[4] That is why Dhana Nanda did not honour Brahmin Vedic scholar Chanakya. In fact, the king kicked him out of his court.

Similarly, the Mauryans were also Shudras. “Chandragupta Maurya was the founder of the Mauryan Empire. Chandragupta was related to the Moriya people but came from a low class.”[5] Quoting from Vishakhadutt’s Sanskrit play Mudrarakshasa and other sources, Pandit Revati Prasad Sharma has concluded, “A dasi (female slave) called Mura was the mother of Chandragupta, the first ruler of the Mauryan dynasty. It was due to her that this clan came to be known as Mauryan. As Chandragupta was born of a female slave, Maha Nanda (Dhana Nanda) wanted his younger son to succeed him instead of Chandragupta. An incensed Chandragupta quit the royal court and with the help of Chanakya occupied the throne of Magadha. According to another story, the queen fell for a Nai and Chandragupta was born of their union. Then, she killed the elderly king, dethroned his son Dhana Nanda and made Chandragupta the king.”[6] . Other sources say that Chandragupta was a Kurmi or a Kushwaha. Whatever may be the truth, what is undisputed is that the Mauryan rulers were Shudras and that all the rulers of this dynasty, including Ashoka, were adherents of either Jainism or Buddhism.

Contribution of OBC-Dalits to the development of language and script

Scriptures and tradition both accord Sanskrit the status of India’s oldest language. Some scholars even claim that it is the oldest language in the world. It is also said that Sanskrit is the mother of all Indian languages and that all Indian languages have their roots in Sanskrit. These two falsehoods have long been rejected by linguistics but are still considered as gospel truth. If Sanskrit is the oldest language then its script should also be the oldest. But Devnagari or Nagari – the script in which Sanskrit is written – is also the script of modern languages like Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Nepali and of the dialects of Hindi-speaking states. It is a comparatively modern script.

Then which is the oldest script of India? Archaeological and historical evidence indicate that Brahmi and Kharosthi are the oldest scripts of India. These are the scripts of Ashokan edicts (269-232 BCE). The Nagari or the Devnagari script has developed from the Brahmi script. Pali, Prakrit, Apabhramsa, Tamil and other languages were written in the Brahmi and the Kharosthi scripts. Besides the edicts, Jain-Buddhist literature also proves the antiquity of these scripts. Not a single Sanskrit text was written in these scripts, because clearly Sanskrit was non-existent then. Hence, Sanskrit is not the oldest language of India. Talking of scripts, according to the evidence available to date, Lalit Vistar, believed to have been written in the 3rd century CE, is the oldest text focused on scripts. It also happens to be the first Sanskrit text that gives a detailed account of the life of Buddha. The text describes 64 scripts prevalent in India and Asia, listing Brahmi and Kharosthi at the first and the second spots, respectively. It should be noted that only Sanskrit texts refer to this script as Brahmi, claiming that Brahma had created it. In the Jain-Buddhist Pali-Apabhramsa texts as well as in the Ashokan edicts, it is called the Dhamma script. Thus “Bambhi” or “Dhamma” is the old name of the Brahmi script. Lalit Vistar even talks of Chinese scripts but Devnagari or Nagari find no mention. Dev script is listed at the 26th spot but it is preceded and followed by scripts such as Hun, Naga, Yaksha, Gandharva, Kinnar, Asur, etc. Hence, “Dev” script is not Devnagari or Nagari. This means that in the Buddhist era, Devanagari script was neither known nor used. Hence, either Devanagari developed later or it was known by a different name then. Like Brahmi, the Brahmins linked Devnagari with the gods saying that it was the script of the Devas. That is because their oldest texts, the Vedas, are written in this script and they consider the Vedic texts as Apaurushey (not the creation of man). Vedas are said to have been created around 5200-5500 BCE. But the Vedas are Smritis, which means that they were passed on from generation to generation orally and were written when the script was invented. Puranas, obviously, are of later antiquity. What about the dozens of Vedangs, Upanishads and Aranyaks? They are claimed to have been written before the Common Era, during the time of Buddha. But their script belies this claim. They were written sometime after the 3rd century CE.

Another big lie that is often propagated is that all the Indian languages, including Hindi and Bangla, have evolved from Sanskrit. This claim also needs to be explored.

A language is distinguished by its syntax – the way the words are arranged to form a meaningful sentence. In Sanskrit sentences, the order of words is of no consequence. A word can be placed anywhere in a sentence and this will make no difference. Thus “Asti Godavari teere eko taru”; “Eko taru Godavari teere asti”; and “Taru asti eko teere Godavari” – all mean one and the same thing, that there is a tree on the banks of the Godavari. But other languages have inflexible rules regarding the order of words, say subject, object, verb or subject or verb, object and subject and so on. In Urdu and Persian, the addition of a nuqta (a dot placed at the bottom of a character) can turn “khuda” into “juda”. Then, look at grammar. Other languages have singular and plural nouns. Sanskrit has singular, dual and plural nouns. Other languages have two or three genders – feminine, masculine and neuter. But Sanskrit has four. Other languages have three tenses – past, present and future. But Sanskrit has five to ten tenses – present, imperative, optative, aorist, etc. But only an abundance of words cannot make a language the mother of other tongues. Rules regarding joining of two words (Sandhi) are also typical to Sanskrit. That is why, Bachchan Singh writes, “It was believed that the growth of north Indian Aryan languages followed the trajectory of Sanskrit-Prakrit-Apabhramsa-modern languages. But now the belief that Hindi, Bangla, etc originated from Apbhraṃśa has been proved wrong.”[7]

The Licchavi Republic, which predated the Nanda and the Mauryan era, had 16 Mahajanpads and the rulers or the key ministers of most of these “major districts” were Shudras. Now, when ancient India was ruled by the Buddhists and the Shudras, obviously, they must have had some language, script and their own literature. It is almost certain that their language was Prakrit, Pali and Apabhramsa and their scripts were Brahmi and Kharosthi. Here, it needs to be mentioned that scripts were invented by painters and sculptors, and not scholars. Not only in India, but in civilizations the world over, paintings and sculptures predated the development of scripts. And who were the painters and the sculptors? Indian culture and scriptures brand them as Shudras. All workers and artisans were categorized as Shudras in India. They made paintings and sculptures based on the popular dances and songs as well as on emotions and human gestures and mannerisms. It is common knowledge that folk languages and folk songs have emerged from the homes and the communities of the worker/artisan classes. Language came first and script later. But language was not created by any one person or a group of persons. It developed from spontaneous sounds as humans sought a medium for exchange of ideas. The sculptors and the painters animated stories, music and dance. They also animated emotions and sounds, first as pictorial and then as sound-based scripts. Different characters or signs were assigned to each sound, which came to be called alphabets. The scholars learnt these scripts later. The scholars spoke first and the painters wrote it down. All the painters, sculptors and other workers were, according to the scriptures, Shudras.

Ashaknuvanstu shushrishan shudrah kartum dwijanman

Putradarratyayan prapto jeebvitkarukkarmabhih

(Manusmriti 10:99)

(If a Shudra is unable to serve the Dwij castes and his wife and children are suffering for want of food etc, then he should work as an artisan for his livelihood and take care of their needs.)

Yah karmabhih prachritaiah shushurshyante dwijatayah

Tani karukkarmani shilpani vividhani cha

(Manusmriti 10:100)

(The works that can be done to serve the dwij castes are different kinds of workmanship and crafts.)

Classical evidence also shows that the elite scholars did not know how to write. They had wisdom and knowledge and they knew the language, but they couldn’t write. And so, the scholars dictated and someone else wrote down what they said. It is said that Ganesha had written down the works of Vyas. And who was Ganesha? The scriptures say that not only Ganesha but the entire Shiva family was Shudra. History tells us that they were non-Aryans. Thus, the script was the invention of the Shudras. Manusmriti clearly describes Ganesha as the god of the Shudras and prohibits Ganyog[8]. Shiva was accepted as a deity by the Aryans later. That is why he is purified with water and “bel-patra” before his worship. Water and “bel-patra” are not offered to any deity except Shiva. Even today, the Kayastha community are prominent in academics and according to the scriptures, the Kayasthas are Shudras. There is enough proof. Even today, like the Shudras, marriages among the Kayasthas are also sagotra (within the same gotra) and not vigotra (between different gotras) as is the case with the savarnas. That is the reason, like the Shudras, the Kayasthas are also facing the consequences of inbreeding.

Linguistics propounds several theories to explain how languages developed. They include: imitation, labour avoidance and yo-he-ho. Language arose from imitating the sounds made by air, water and animals, the heave-ho of labourers, the “haiya-ho” of the fishermen, the songs of rural women pounding or grinding paddy, the “thak-thak” sound made by the makers of brass and copper utensils, the songs of the Adivasis, the sound of the rain and the waterfalls, the stomping and the songs of the country maidens and so on. All these characters were Shudras or Atishudras. So, the OBC-Dalits contributed directly to the development of sound, words, alphabets and thus, language. In evolution, things move from the less developed to the more developed, from the crude to the sophisticated. Therefore, it is unscientific and against common sense to presume that a rich and sophisticated language like Sanskrit gave birth to comparatively less developed Prakrit, Apabhramsa and folk languages. In fact, the reality was the other way round. The trajectory of development must have been folk tongues, Apabhramsa, Prakrit and then Sanskrit. Ayodhya Prasad Khatri contends that among the various types of Khadi Boli Hindi, the “Maulvi-style” is the most potent and elegant. He classified Khadi Boli into five categories – “Thet Hindi, Panditji’s Hindi, Munshiji’s Hindi, Maulvi Saheb’s Hindi and Eurasian Hindi.”[9] What is “Thet Hindi”? It is the Hindi of the common folk, of the Shudras.

Contribution of Dalit-OBCs to the development of ancient Indian literature

There is a huge and varied corpus of literature and folk literature in Prakrit, Pali and Apabhramsa languages, inspired and influenced by Jain and Buddhist religions. Brihatkatha (Baddkaha) is the oldest and the biggest compilation of folk tales, which was written in the Paisachi Prakrit. According to Western scholars, it was written in the 1st or the 2nd century CE. In view of the immense popularity of this book, some of its stories were later translated into Sanskrit. The compilations of these translated stories include Katha Saritsagar, Brihatkathamanjari, Vetalpanchvishanti, Simhasandwatrishinka and Shuktasaptati. These compilations inspired the translation and publication of several compilations of moral stories like Panchatantra, Hitopadesh and Jatakmala. The Prakrit and Apabhramsa languages, the folk languages that evolved from them and the folk literature are the gift and the heritage of the Shudras.”[10]

The world-famous Buddhist universities such as Nalanda, Vikramshila and Odantapuri – all in Bihar – were burnt down in Brahmin-Sraman conflicts. A detailed description of these universities can be found in the travelogues of Chinese itinerants and students of Nalanda University, Hsiuen Tsang and I-tsing. The kings, whether Jains or Buddhists or believers in Brahmanism, except the Shung and some other dynasties, did not promote confrontation between the Jain-Buddhist and Brahman religions. The Gupta kings even built Viharas and educational centres for the Buddhists. Only the Brahmin gurus, priests and pandits abhorred the Jain-Buddhist Sramans because the latter did not believe in god, the Vedas, birth-based varna and caste, and yagna and other rituals. They propagated equality, which adversely impacted yagna and other rituals conducted by purohits. That is why the Brahmins and the purohits always wanted to destroy the Buddhist centres of knowledge. However, they could not do that for a long time because these centres enjoyed the protection and the patronage of the rulers. Even kings who believed in the Brahmanical religion enriched and preserved these universities. But they did ensure that the centres which imparted education only in Buddhist and Jain religions and scriptures, also taught the Vedas. Besides Pali, Prakrit and Apabhramsa languages, these centres also began teaching Sanskrit. This was true of the Guptas, too. But still, these centres primarily remained centres of Buddhist learning. During the rule of Indian dynasties, these Buddhist universities remained safe and secure. But with the advent of the Turk and the Afghan rule, especially once Bakhtiyar Khalji, the military general and governor of the Slave Dynasty, became the ruler of Bihar, the Brahmins managed to persuade him to raze these universities. It is worth remembering that Bakhtiyar Khalji did not destroy Hindu temples, just Buddhist universities. Why did he do so? It is said, “An exhausted Bakhtiyar fell ill after the Battle of Tarain. He was cured by Brahmin Vaidyaraj Rahul Shribhadra. The king was given the Quran to read. The Vaidyaraj coated corners of the pages of Quran with an invisible medicine. As the king touched his tongue and used his saliva to turn a few pages of the Quran, he ingested the medicine and was cured. He returned the favour by burning down Nalanda.”[11]

Some say that this Vaidya was the Acharya of Nalanda while others describe him as the royal physician of the previous Hindu king. The latter is more likely. The Vaidya was a Brahmin and he must have demanded the destruction of Nalanda and Vikramshila as his reward for curing the king. Bhartendu has written in his play, Bharat Durdasha, “Lari Vedic Jain dubayee pustak sari / kari kalah bulayee javan sain puni bhari/ tin naasi budhi, bal, vidya bahu vari.”

What is notable is that during the reign of Bakhtiyar Khalji, besides Maulvis, scholars of Sanskrit were also patronized by the royal court and this tradition continued throughout the Mughal era. “Even during the reign of a fanatic Muslim like Aurangzeb, Sanskrit pandits were patronized by the rulers. Pandit Raj Jagannath, the propounder of Rasa Siddhanta was a scholar and a poet in the court of Shah Jahan. The courts of Babar, Humayun, Akbar and Jehangir – all had scores of Sanskrit poets and scholars. Most of the treatises on Sanskrit poetry, delineating its theory, were written by the scholars enjoying the patronage of the Mughal Durbar.”[12] However, the poets and the scholars of Prakrit, Pali or Apabhramsa did not get state patronage during the Mughal rule and these languages and their literature were largely ignored and languished. That is the reason, when the British, in 1800 CE, were appointing “Bhasha Munshis” for exploration, translation and publication of literature in ancient Indian languages at Fort William College in Calcutta, they couldn’t find scholars of these languages. As a result, work was done only on Sanskrit texts.

Against this backdrop, we need to remember that lakhs of books in Prakrit and Apabhramsa languages were preserved in the universities like Nalanda. They were the products of Jains, Buddhists and the Shudras. This huge corpus of literature was reduced to ashes. The Siddha and Nath literature in Apabhramsa language was also preserved in Nalanda. “Most of the Chaurasi Siddhs [84 accomplished scholars] were students and teachers of this university and most of them were Shudras. Dombhippa was a Dom. The leading Siddhas and Sants include Sarhappa, Luippa, Shabarppa, Bhusukappa, Kanwanppa, Kambalppa, Gundrippa, Jalandharippa, Darikappa and Dhamppa, whose voluminous writings and their excerpts are still available.”[13]

Thus we find that besides the development of language and script, the OBC-Dalits also contributed immensely to the development of literature in ancient India.

Contribution of Dalit-OBCs to the development of Sanskrit literature

As Sanskrit is closely related to Hindi in terms of vocabulary and grammar, we also need to dwell on Sanskrit literature. Valmiki is one of the earliest Sanskrit poets and so is Vyas, the author of the Mahabharata and the Vedas and the Vedangs. Both are believed to be Shudras – the first a Dalit and the second an OBC. We need to talk about them, too

The scriptures and the tradition both say that Valmiki, the author of Ramayana, was a Dalit (Bhangi or Chandal) and Vyas, the writer of the Mahabharata, was an OBC (Nishad). Valmiki authored many texts, including the Ramayana and Yog Bashisht, while Vyas wrote Gita, the Vedas, all Vedangs (Brahman, Aranyak, Upanishad, etc), scriptures and Puranas. That covers almost the entire Vedic literature. All the Vedic scriptures, which form the foundation of the Brahmin or the Sanatan religion, were penned by these Dalit-OBC poets. Then what is left to discuss? Why should we blame the poor Brahmins and their Brahmanism? Why do we sully their reputation? Why don’t we admit that as our ancestors propounded the Vedic, Brahmin or Sanatan religions and their philosophies, these religions, their philosophy and their ideology are ours?

Alright, let us accept this argument. But then, what of the movements launched by Buddha, Kabir, Phule, Ambedkar and Periyar, some of which continue to date? Were all of them useless? That is not at all the case. This is a sociological and philosophical issue which should be discussed and debated. Valmiki has himself referred to the legend of the dacoit Ratnakar in his Aadhyatma Ramayana, Anand Ramayana and Kirtivas Ramayana. The Skanda Purana also relates the same tale. In Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas says, “Ulat naam japat hari nama, Valmiki bhaye Brahma samana.” Valmiki’s mother Charshini and his father Pracheta both were Brahmins. A Bhil woman abducted Valmiki when he was a child and brought him up. That is how like the Bhils, he ended up as a bandit. Thus, given his adoptive mother and his deeds, Valmiki was an Atishudra (Bhangi, Chandal). But in the Valmiki Ramayana, when, after her stay at the Valmiki Ashram, Sita is again subjected to a trial by fire in the court of Rama, Valmiki declares, “I, Valmiki, the son of Pracheta [Brahmin], the truthful one, declare on oath that Sita is as pure as fire.”

Similarly, Vyas is the son of Brahmin Rishi Parashar. His mother Satyawati is a Nishad. Thus, Vyas is an OBC only from his mother’s side. Anulom-Vilom marriages were common in those times. Scriptures say that a child born of a union between a man of a higher Varna and a woman of a lower Varna belongs to the varna of his or her father. On the other hand, the child of a woman of higher varna and a man of a lower varna is a Shudra.

Going by the above stories, both Valmiki and Vyas were not only Brahmins but were also brahmanical. Hence, it is unlikely that they were Dalits or OBCs. Their works and their beliefs are questionable. Valmiki is considered “Aadi Kavi” (the ancient poet) and Vyas is believed to be the writer of the Vedas. Given these facts, the Ramayana should have predated the Vedas. But that is not so. Vedas are definitely older. Hence, the caste status of both is doubtful. We cannot say with any degree of certainty that Valmiki and Vyas were Dalits and OBC, respectively.

But Manusmriti and many other Smritis and Puranas also say that the progeny of a Brahmin father and a Shudra mother is considered a Shudra. Going by this definition, Vyas was a Shudra. Some scholars have tried to link Valmiki’s father Pracheta with Varun and others, with Rishi Chyavan.

The Vedic tradition tells us that the Bhrigus were the makers of chariots and hence Shudras. Their wives, Hiranyakashipu’s daughter Divya and Puloma’s daughter Paulomi, belonged to a Rakshas clan and so they were also non-Aryans (Rakshas). Divya gave birth to Chyavan Rishi and Paulomi birthed Shukracharya. Chyavan was born with “prakrishta” (a high level of) consciousness and hence Pracheta was his other name. This is also confirmed by Ashwaghosha’s treatise Buddha Charitam[14]. Thus, in terms of his birth and his lineage, Valmiki was a Dalit or a Shudra.

According to Dalit writer and thinker Kanwal Bharti, “As far as Valmiki’s mythological tale of Rama is concerned, it cannot be termed as a work that upholds feudal values. The fact that a hunter had to face a curse for killing one of a pair of cranes shows how the epic depicts resentment against the feudal social order. The killing of Shambuk at the hands of Rama is also important from the perspective of Dalit identity. Valmiki lived in the feudal era. He must have been dependent on state patronage. As such, a no-holds-barred assault on the prevailing social order would have translated into Valmiki being held guilty of sedition, with death sentence as a punishment. That is why Valmiki used the language of feudalism to underline the need for social change. Though we cannot consider the Ramayana as a part of Dalit literature, we also cannot dub Valmiki as an unquestioning supporter of feudal values.”[15]

Similarly, if we concede that Vyas was the Shudra (OBC) son of a Shudra mother, then it is also true that his Mahabharata is a tale of crossbred progeny. Almost all the male characters of the Mahabharata were born either from Niyog (an ancient Hindu practice that permitted either the husband or the wife who had no child by their spouse to procreate a child with another woman or man) or via illicit relationship (invocation of devas). The varna and caste system, as depicted in the Mahabharata, is quite liberal and flexible – much more so than the other Brahmanical texts. Vyas uses the character of Yudhisthira to reject the theory of birth-based varna and caste system. Whatever may be the stories regarding the life and the works of Vyas and Valmiki, what is certain is that in the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the Varna system and caste discrimination is not as narrow and strict as it would become subsequently. Valmiki and Vyas may not have belonged to the Dalitbahujan tradition, but they did try to make the varna and caste system more liberal and flexible. This is another way in which the Dalits and the OBC contributed to the development of Sanskrit literature.

Sudraka, the author of the famous Sanskrit play Mrichchhakatika, is also said to be a Shudra. The storyline of the play, which negates feudalism and promotes democratic values, also proves that he was a Shudra. It is also said that Kalidas belonged to the Gadaria caste. However, his writings betray a love for feudalism. Many Vedic mantras and verses are attributed to Shudra Rishis. Kavash Aelush, the writer of many Rigvedic mantras, is said to be a Shudra. The Ashwini Kumars did not have the right to consume “soma rasa” (an intoxicant) because they were Shudras. Rishi Raikva and Mahidas are prominently mentioned in the Vedas. Mahidas was also a king. Another Shudra king Janshruti also finds mention, whom Rishi Raikwa is said to have taught the Vedas. Mahidas is said to be the author of the Aitareya Brahmana and of the Upanishads. There are many such kings and Rishis but they do not represent the Dalitbahujan tradition.

Contribution of Dalit-OBCs to the development of medieval literature

The medieval literature is divided into two parts – Bhaktikal and Ritikal. The latter, Ritikal, is the era of the feudal lords and its literature reflects this fact. But Bhaktikal belonged solely to the Shudras. Bhaktikal begins with the writings of Nirguna saints like Kabir and others. Next came Tulsi, Sur and others who were poets of the Saguna Bhakti stream, which had its origins in the puja-kirtan tradition of south India. Nirguna literature is again divided into two parts – Gyanaashrayi and Premaashrayi. The Gyanaashriyi stream comprised poets like Kabir, Nanak, Raidas, Peepa, Dadudayal, Sundardas, Malookdas, Amir Khusro and others. The poets of the Premaashrayi stream consisted of Jayasi, Kutuban, Manjhan, Mulla Daud, Usman, Sheikh Nabi, Kasimshah and Noor Mohammed. The Rambhakti branch of the Saguna stream, besides Tulsi, consisted of poets like Agradas, Nabhadas, Pranchand, Hridayram and Keshavdas whereas the Krishnabhakti branch, besides Surdas, included Kumbhandas, Parmananddas, Krishnadas, Nanddas, Chhetswami, Govinddas, Raskhan and Meerabai. All the poets of both the branches of Nirguna stream were either Shudras or Muslims. Even among the poets of Saguna stream, Nabhadas, Kumbhandas and others are said to have been Shudras. We all know that the Nirguna consciousness is inspired by non-Vedic traditions such as Siddha-Nath and Sufism while the Saguna stream owes its origins to the Vedic-Puranic tradition. The writings of Kabir, Raidas, Nanak and others reflect their social concerns. They do not believe in high and low, in discrimination and religious ritualism. They talk of equality. The poets of the Saguna stream talk about the incarnations of god and advocate the varna system and social discrimination. Clearly, while the Nirguna stream acknowledges and accepts the Dalit-OBC concerns and consciousness, the Saguna stream is about Brahmins and Brahmanism. It should also be remembered that the number of Nirguna poets is higher than that of Saguna poets. Another point to be noted is that all the poets of the Bhaktikal used folk languages. While the Nirguna literature is in Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Urdu or a mixture of these, the Saguna works have been written either in Awadhi or in Brajbhasha. The reason was that these poets wanted their voice to reach far and wide.

Thus in terms of both language and contents, the Bhakti literature is in tune with the Dalits and the OBCs and most of its authors belong to these communities. The Muslim poets were also Pasmanda, who are categorized as OBCs now. So, the Dalit-OBCs played a direct role in the development of medieval literature.

Contribution of Dalit-OBCs to development of modern literature

While the medieval era was about the Turks, Afghans and Mughals, the modern era belonged to the British. Education in the English language initiated a renaissance in India and gave birth to scores of social reformers and thinkers. Brahmo Samaj, Prarthna Samaj, Satyashodhak Samaj, Arya Samaj and other movements were led by the likes of Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Keshavchand, Ishwarchand Vidyasagar, Jotirao Phule, Chhatrapati Shahuji Maharaj, Dayanand Saraswati and Vivekananda to educate and reform society. They were succeeded by Balgangadhar Tilak, Agarkar, Ranade, Gandhi, Periyar, Ambedkar and others. Education, which was confined to the gurukuls and the madrasas, became available in modern schools and colleges. Formal and systematic imparting of education began. Though education was open to all, the Dalit-OBCs and women remained deprived of it in the initial stages. Several movements and campaigns ensured that education became accessible to all. But the education system was infused with Brahmanical beliefs and outlook. With the passage of time, the Dalits and OBCs and the women started getting an education and the movements launched by Phule, Ambedkar and others transformed education and literature both. Progressive and pro-people writings began and the history of the women and the Dalits and OBCs found their due place in literature and history. Today, Dalitbahujan literature occupies the centre stage in education and literature.

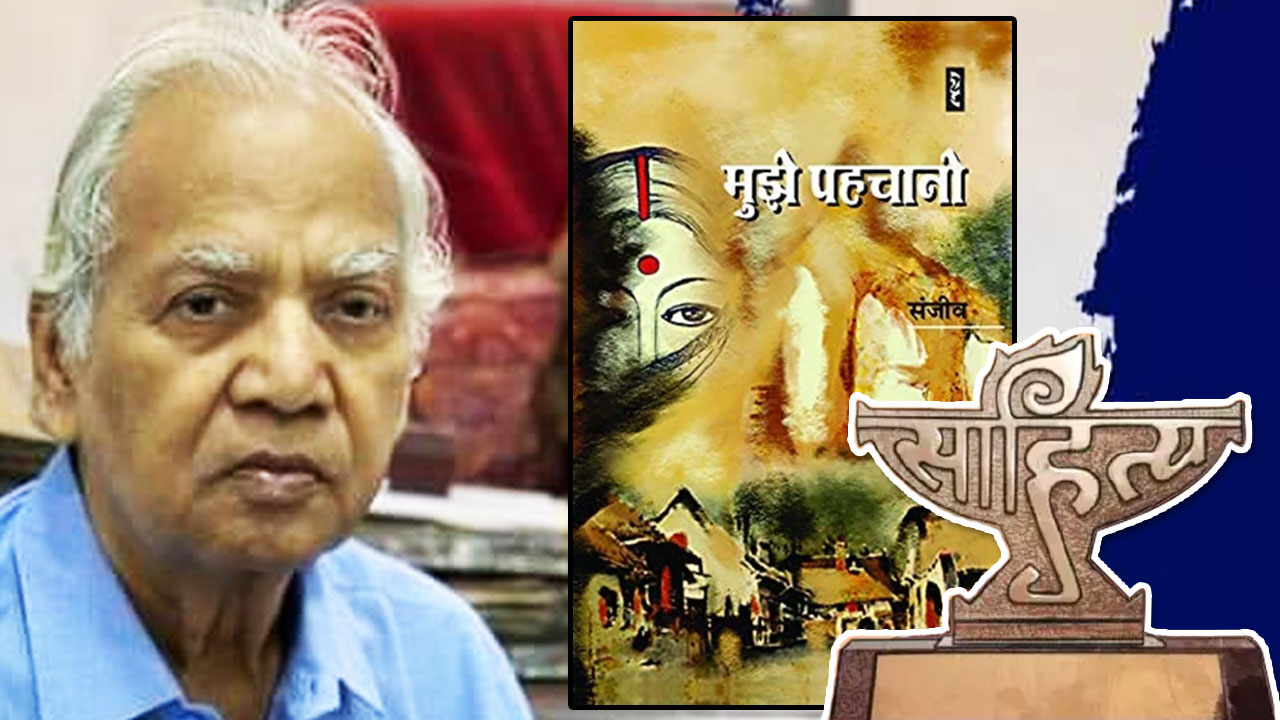

The poetry in Khadi Boli and the early fictional writings, which were very popular, were not accorded a place in literature. Hindi scholars like Ayodhya Prasad Khatri had to launch campaigns to ensure that their works were treated as literature. Writings of Devaki Nandan Khatri, Gopal Ram Gahmari (Sahu), Ibne Safi, Kushwaha Kant, Gulshan Nanda and others, though well received by the public, were not accepted as a part of literature. However, now they are considered literature. If literature languished initially, it was because like in the ancient gurukuls, entry into educational institutions was limited to the Brahmins and the princes (feudal elements). The Kayastha and the Khatri communities have been well educated and they have had dynasties among them, too. Writing is their tradition and their legacy both. But they won acceptance in the academic world only after celebrated authors like Premchand started writing in Hindi, instead of Urdu. Otherwise, like the Shudras, they too were treated as pariahs. Devaki Nandan Khatri’s Chandrakanta Santati inspired many TV serials and films. Similarly, a series of hit films like Kajal, Kati Patang, Neelkamal, Khilona, Pardesi and Nagin were based on novels by Gulshan Nanda. But these writers were never accepted as litterateurs by the academic world. On the other hand, several notables like Bhartendu Harishchandra, Jaishankar Prasad, Mahadevi Verma, Phanishwarnath Renu, Rajendra Yadav, Mannu Bhandari, Giriraj Kishore and Chandrakishore Jaiswal, and others like Chauthiram Yadav, Ramdhari Singh Diwakar, Rajendra Prasad Singh and Premkumar Mani have been accepted as leading lights of the Hindi literary world. Then, there are well known Dalit writers and poets like as Hira Dom, Achhootanand, Omprakash Valmiki, Kanwal Bharti, Mohandas Nemisrai, Sheoraj Singh Bechain, Malkhan Singh, Buddha Sharan Hans, Jaiprakash Kardam and Tulsiram who have won recognition and acclaim. Among the Adivasi writers, Ramdayal Munda, Vandana Tete, Mahadev Toppo and Anuj Lugun have enriched Hindi language and literature with their works.

Thus, it is clear that the Dalits and the OBCs played a key role in the development of Hindi language and literature. It is necessary to work collectively, in coordination, to expand their role.

References:

[1] Romila Thapar, Bharat Ka Itihaas, Rajkamal Prakashan, New Delhi and Wikipedia

[2] Romila Thapar, Bharat Ka Itihaas, Rajkamal Prakashan, New Delhi, p 50

[3] Ibid

[4] Gunakar Muley, Itihaas, Sanskriti Aur Sampradayikta, Yatri Prakashan, New Delhi, p 133; and Wikipedia

[5] Romila Thapar, Bharat Ka Itihaas, Rajkamal Prakashan, New Delhi, p 61

[6] Pandit Revati Prasad Sharma, ‘Nai Varna-Nirnay’ in Upekshit Samudayon Ka Atma Itihas, ed Badri Narayan, Vishnu Mahapatra and Anant Ram Mishra, Vani Prakashan, pp 80-81

[7] Dr Bachchan Singh, Hindi Sahitya Ka Doosra Itihas, Radhakrishna Prakashan, New Delhi, p 15

[8] Gunakar Muley, Itihaas, Sanskriti Aur Sampradayikta, Yatri Prakashan, New Delhi, p 95

[9] Ayodhya Prasad Khatri, Ayodhya Prasad Khatri Smarak Granth, Bihar Rajbhasha Parishad, Patna, p 203

[10] Dr Rajkishore Singh and Devishankar Mishra, Sanskrit Sahitya Ka Itihaas, Prakashan Kendra, Lucknow

[11] Wikipedia and different blogs

[12] Dr Rajkishore Singh and Devishankar Mishra, Sanskrit Sahitya Ka Itihaas, Prakashan Kendra, Lucknow, Wikipedia and different blogs

[13] Charyapada and Wikipedia

[14] Kishore Kunal, Dalit Devo Bhavah, Part 1, Prakashan Vibhag, Government of India, New Delhi

[15] Kanwal Bharti, Dalit Sahitya: Kuch Aalochanayein, Sankalpika, Patna, September 1997, p 29

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)