Hul through the eyes of Indian and foreign historians

Santhal Pargana was once known as the Terai of the forests. It was also known as Daman-e-Koh (sometimes Damin-i-Koh), that is the bosom of the forests. Before settling at Daman-e-Koh, the Santhals inhabited the areas around Hazaribagh, Giridih, Ghasbhum, Manbhum, Birbhum and Midnapore. Even before that, they populated “Chai-Champa”. From 1810 onwards, at the prodding of the British, they began settling in the area which was demarcated as Daman-e-Koh by James Parry Wood in 1832-33. In 1837-38, James Potente was appointed as the Superintendent of Daman-e-Koh. He was in charge of land bandobast and collection of land revenue. Though he was a well wisher of the Adivasis, his policies were anti-Santhal. He patronized the landlords and the moneylenders. With time, the burden of land revenue on the Santhals kept growing and so did the atrocities committed on them by the landlords and the loan sharks. There was no one to provide justice to them. The local magistrate’s court was at Deoghar. The Santhals had to travel to Bhagalpur, Birbhum or Berhampore, whenever a major dispute arose. Those committing atrocities on the Santhals included landlords, moneylenders and their musclemen. The police sided with them. The open loot by policemen, moneylenders and the landlords was one of the reasons that led to Hul (Santhan Rebellion).

Different historians have done detailed studies on the causes and the outcome of Hul and tested the authenticity of the claims pertaining to the rebellion.

Foreign historians

In his book, The Annals of Rural Bengal, William Wilson Hunter presents a detailed account of Hul. The book, published in 1838, analyzes the reasons that led to Hul and counts usurping of their land by the zamindar, their brutal exploitation by moneylenders, corrupt and tyrant police, crooked government officials and molestation of Santhal women by employees of the railways, among them. The moneylenders used to levy high interest on loans. They had two sets of weights. The heavier ones called “kena ram”, were used when buying cereals or other produce from the Santhals, and the lighter ones called “becha ram” were used when selling things to them. They cheated and defrauded the Santhals to no end. They even used to forcibly seize their cattle and snatch away the iron ornaments worn by their women.

However, Hunter believes that the construction of the railways had a positive impact on the lives of the Santhals. They got work. Moreover, getting employment in tea gardens brought prosperity to them. However, these arguments are hollow. The fact is that a large chunk of the land of the Santhals was taken away from them in the name of the railways. Forests were felled, which caused immense pain to them. They did get some cash but they had no use for it. They did not save it. They believed in eating, drinking and being merry and celebrated all kinds of festivals. They squandered away their money. The Santhals were forced into “begar” (unpaid labour) for railway construction work and sexual exploitation of their women was rampant. In tea gardens, they were treated like slaves. They were forcibly displaced in large numbers from Daman-e-Koh. Thus, Hunter’s claim that the construction of the railways and tea gardens benefited the Santhals does not hold water.

E.G. Man’s book Sonthalia and the Sonthals came out in 1867. He gives a detailed account of the Santhal Hul. He cites almost the same reasons as Hunter – moneylenders juggling figures, pushing Santhals into debt trap, fleecing them and forcing them to cough up interest many times what was actually due. The Santhals were pushed into bondage that lasted for generations, the moneylenders and the corrupt police being in cahoots, even committing atrocities on them. Man also lists Santhals’ lack of faith in the courts and the Adivasi philosophy of living for today and not worrying about tomorrow among the reasons that led to Hul.

According to E.G. Man, the ground for Hul had been in the making since 1832. That was when the courts started favouring the moneylenders. Compound interest at the rate of 40 to 75 per cent per annum was extorted from the borrowers.

All this led to Hul, which took the lives of thousands of Santhal men and women. British troops ruined and pillaged Santhal Pargana. The Santhals were forced to surrender. E.G. Man has praised the courage of the Santhals. He considers the arrival of the Christian missionaries in the areas inhabited by the Santhals as a boon for them. The Christian missionaries did provide them better educational and health facilities. But at the same time, they held the cultural values of the Santhals in contempt. That led to Santhals developing an inferiority complex vis-à-vis their own culture and embracing Christianity.

After W.W. Hunter and E.G. Man, the writings by L.S.S. O’Malley on Hul are considered the most important.

In the Bengal District Gazetteers Santal Parganas, L.S.S. O’Malley lists British officials’ apathy towards the Santhals, the loot by moneylenders, corruption by government officials, nexus between the police and the corrupt elements and their resultant oppression as responsible for Hul. He writes that the Santhals were seething with anger. The Bengali moneylenders and dikus (outsiders) were also oppressing and exploiting the Santhals. They had to travel to faraway Deoghar to file complaints, which was difficult, trouble-filled. The moneylender would be at their door while justice would be miles and miles away. O’Malley writes that while the moneylenders maintained their books meticulously, the Santhals used a rope with knots to keep an account of their loans. The knots denoted the number of times they had taken loan from the moneylenders while the distance between the knots denoted the duration of the loan. The moneylenders got thumb impressions from the Santhals on mortgage documents, which were sort of bonds. If any case went to the courts, they presented their doctored books and the bonds carrying the thumb impressions. The Santhals only had the rope as evidence for their defence. The moneylenders were shrewd and dishonest while the Santhals were ignorant and docile. When the loans remained unpaid, the moneylenders used their musclemen to seize the cattle and birds of the Santhals. The courts also did not do justice with the Santhals. They would forward the cases to the police for investigation but the police would already be in collusion with the usurious moneylenders and capricious landlords.

The Santhals often failed to clear the loans and would be forced to work as farm hands of the moneylenders for generations. However, O’Malley glosses over the fact that the Santhals were also exploited at the railway construction sites and that railway employees sexually exploited Santhal women.

Bengal under the Lieutenant Governors by Charles Edward Buckland also furnishes a detailed account of Hul. The book is based on Buckland’s own report, published in 1901, which claims that the Hul was a revolt against the Bengali moneylenders. The Bengali moneylenders fleeced the simple, ignorant Santhals. Once caught in the trap of the moneylenders, the Santhals, along with their families, were forced into serfdom for generations. Buckland doesn’t blame the government of the East India Company and describes the Santhals as cruel and savage barbarians. Also, he is not ready to accept that railway employees exploited the Santhals, though he does admit that the Santhals did not have access to courts. He also admits that during Hul, the Santhals gave a tough fight to the British troops. But Hul was savagely suppressed. Around 25,000 Santhals were killed and their villages were burnt down.

W.G. Archer and W.J. Culshaw have also done significant work on Hul. Their article, The Santal Rebellion, was published in the special “rebellions” number of Men in India, a journal edited by celebrated anthropologist M. N. Roy and published from Ranchi. The special number also carried some folk songs from Hul. The songs speak of how the loot by moneylenders and landlords and the failure of the officials to secure justice for them forced the Santhals to revolt.

“Why did Sido-Kanu revolt?

Why did they start Hul?

Moneylenders Kenaram and Becharam

Cheated the people and caused Hul.”

Culshaw says that the Santhals were deeply attached to their land. They believed that the land was the repository of benevolent souls and to keep these souls happy, they needed to save their land. He quotes an order issued by the brothers Sido and Kanhu to the Santhals to sanctify the villages to keep the souls happy. Before Hul, Sido-Kanhu dispatched plates made of Sal leaves with dry rice grains, oil and vermillion to placate the souls. But in Archer’s view, Hul was a foolish enterprise and the Santhals had to pay a heavy price for it.

Santhal folk songs tell us that Hul was indeed led by Sido, Kanhu, Chand and Bhairav, but women also participated in it in a big way.

“Phoolo-Jhano you wielded the sword,

You displayed greater valour than your brothers

At Bhognadih you took a pledge

You did not put up with the atrocities of the moneylenders who fleeced you,

You carried swords in both your hands,

You taught a lesson to Kenaram-Becharam,

You killed 21 British soldiers

Both of you have become immortals.”

During Hul, Phoolo-Jhano not only showed what women power was but they also took up the sword to protect the honour of Santhal women

“Phoolo-Jhano both of you took part in Hul

You displayed the strength of women

You raised your sword against the atrocities of the British

You raised your sword to protect the honour of women.”

Indian historians

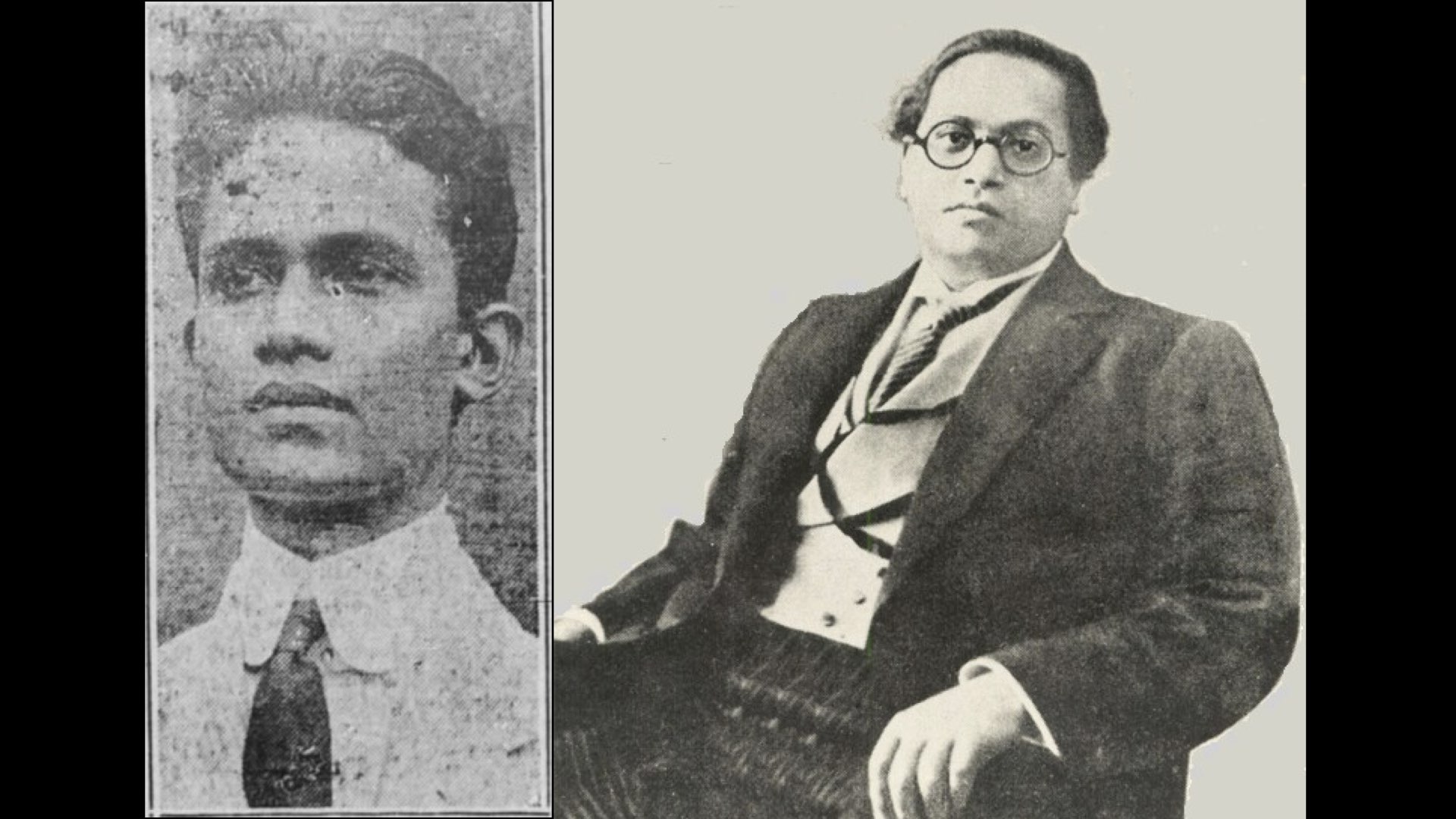

Among Indian historians, the most important research work is that of Kali Kinkar Dutt. The Santal Insurrection of 1855-57 is an important book on Hul. This book, divided into four chapters, was published in 1940. The first chapter is about the factors that led to the revolt, the second is on its genesis, the third on how it was crushed and the fourth on its fallout.

In Dutt’s view, the land revenue being increased many times over, exploitation of the Santhals by the moneylenders and usurpation of their land by the zamindars were among the reasons that triggered Hul. The government began granting land rights in Santhal villages to non-Adivasis. That was why the Santhals hated the rulers of Pakud and Maheshpur. Dutt also mentions another reason, which the British historians chose to gloss over. That was the sexual exploitation of Santhal women by railway contractors and employees. Corruption was rampant in the courts and at police stations. Where could the Santhals have gone for justice?

According to Dutt, Sido and Kanhu gave a religious and divine hue to the rebellion. They told the Santhals that Thakur (their deity) had appeared before them and urged them to launch Hul.

On 30 June 1855, a big congregation of Santhals was organized at Bhogandih. It was attended by more than 10,000 Santhals. At this gathering, Sido and Kanhu announced that their gods wanted the Santhals to break free from the stranglehold of their exploiters. They sounded the bugle for an armed rebellion and a daroga (inspector) called Mahesh Dutt became its first victim. The rebellion soon spread to Godda, Pakud, Maheshpur, Murshidabad and Birbhum.

According to K.K. Dutt, besides the Santhals, members of other castes also participated in Hul. The rebellion was crushed and 251 prisoners were sentenced. They included 191 Santhal, 34 Nai, five Dom, six Dhangad, seven Kol, one Rajwan and six Bhuiyyan. Dutt says that had the police and the administration not been corrupt, Hul would not have happened. After Hul, the government constituted the Santhal Pargana and took steps to understand the problems faced by the Santhal and the conditions in which they lived and took steps to redress their grievances.

Dr S.P. Sinha has written a book titled Santal Hul (Insurrection of Santhals) 1855-86. The first chapter of the book is devoted to the studies of A.S. Bidwell and W.W. Hunter. On the basis of Bidwell’s report, Sinha has conveyed the views of Captain Sherwill, Charles Barnes and others. Captain Sherwill doesn’t think that the increase in land revenue led to Hul. According to him, the Santhals were happy with land revenue officer Potente. Barnes also believes that the Santhals had no issues with the zamindars and the moneylenders. They participated in Hul only because they believed that they had to follow the divine ordainment. A certain Grant believes that Hul was triggered solely due to the atrocities committed by the police and that the moneylenders, the zamindars and the corruption in the government machinery had nothing to do with it.

Dwelling on the problems faced by the Santhals, Sinha writes that they were desperate to free themselves from the slavery of the moneylenders and the zamindars. They began toiling in railway projects in the hope of a better life. Sinha does not attach much significance to the exploitation of the Santhal men and women by the railway staffers. The attachment of Santhals to their land was not only economic, but also emotional. For them, their land was sacred. That was why when they were deprived of their land, they were so deeply hurt that they launched Hul. The Santhals believed in ‘Abua Raj’ (self-rule). Subservience to anyone was not acceptable to them.

Talking about the long-term consequences of Hul, Sinha says that for the Santhals, Hul was not only about laying down their lives but it also symbolized the promise of a better future, although Hul left thousands of Santhal women widowed and hundreds of children orphaned. It was decades before Santhal villages got repopulated.

In his book Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Ranjit Guha has dwelt in detail on the Santhal rebellion (Hul), the Kol rebellion and Birsa Munda’s Ulgulan.

Guha throws light on some untouched aspects and incidents of Hul. The Santhals correctly identified their enemies and they could no longer put up with the exploitation. They not only launched a violent movement against the zamindars, the police and the moneylenders, but they also targeted the British and the Bhadra Bengalis, who were associates and patrons of their oppressors and who, in their view, were symbols of class discrimination.

At the same time, the Santhals also aired their protest by adopting the culture and the symbols of their enemies. The idea was to convey to their enemies that the Santhals could also become powerful by adopting the symbols which the former thought made them superior or elite. That was why Sido wrote ‘Thakur Ka Parwana’. This written document was seen as a magical force, mobilizing the Santhals, and more than 10,000 of them gathered at Bhognadih. It was a warning to the dikus that the Santhals, too, had learnt to read and write and that had made them powerful and that the dikus had better move base to Arah and Chhapra on the other side of the Ganga. The moneylenders maintained their accounts in writing and used the books to loot the Santhals. The written message from the Santhals was meant to warn these moneylenders that the Santhals wouldn’t let them fudge the accounts.

The Santhals also performed puja of Hindu deities like Durga and Ganpati. Two Brahmins were abducted for the purpose. Besides, the Santhals also invited non-Santhal castes and communities to join forces with them. They felicitated a person of the Gwala caste. Sido and Kanhu tied a pagdi on his head and thus made supposedly ‘low’ castes, partners in their movement. During Hul, Sido, Kanhu, Chand and Bhairav wore red attire. The red colour was a symbol of revolution intended to convey that the Santhals would establish Abua Raj (self-rule).

Ranjit Guha writes that the Santhals also committed robberies at the homes of the moneylenders to signal that the revolt against them had begun. According to Guha, Sido held discussions with the Manjhi (headmen) and Patganait (sarpanches) for over two months before launching Hul.

Another distinct feature of Hul was that women, too, took part in it. This is revealed by Morahkaramko Riyak Katha (folk stories). According to Ranjit Guha, as always, women participated in Hul shoulder-to-shoulder with men. Women, too, were arrested and 45 of them were sentenced.

Ranjit Guha believes that the Santhals intended to cripple their enemies through robbery and arson at their homes and establishments. They believed that by looting the zamindars and moneylenders they were only taking back what was theirs because the zamindars and the moneylenders had built their property by looting them. The Santhals believed that their Thakur had allowed them to loot and pillage. Guha also talks about the unity and camaraderie among the Santhals. A feeling of solidarity among them and their belief in enthusiastically working together made them join Sido and Kanhu’s efforts.

Hul was a people’s revolution in the sense that besides the Santhals, 13 other castes joined it. They included Bairagi, Kori, Bocha, Khati, Dhangad, Dom, Gwala, Hadi, Julaha, Kalwar, Kumhar, Lohar and Teli. They took part in Hul along with the Santhals. Thus people joined this rebellion rising above the considerations of religion and caste.

Guha has also studied the ways and means that were used for spreading the message of Hul. The Santhals used Sal-wood baskets with oil, vermillion and rice for spreading the message. The people were mobilized by performances involving musical instruments like Mandar, Dugdugi and flute. The Santhalese slogan of “Abua desh, abua raj” evoked a State where people would be free, there would be no exploitation and the locals would get priority due to them.

This article won’t be complete without discussing Adivasi Vidroh, a book based on the revised version of the PhD thesis of Kedar Prasad Meena. His research concluded that Hul was the response to the exploitation of the Santhals by the moneylenders, the loot of their land and sexual exploitation of the Santhal women by railway employees. He also believes that the Santhals’ yearning for freedom and self-respect also pushed them to rebel in the face of such oppression.

Meena notes that the Santhals undertook Hul after detailed deliberations and after considering all other available options. He writes that Hul leader Sido had himself met Potente to apprise him of the problems being faced by the Santhals and had sought redressal. However, Potente insulted and abused him and shooed him away. Left with no option, Sido mobilized the villages using the story of vision from god and the basket of sal wood. Ultimately, Hul was launched on 30 June 1855 with the massive assemblage at Bhognadih. Hul was a modern battle, waged using traditional arms. The Hul aimed at establishing a modern, exploitation-free society with the aid of primitive weapons like bow and arrow and axe.

According to Meena, the concept of Abua Raj was based on democratic values and had a wide canvas. After Hul, the British initiated many reforms but the Adivasis were not satisfied with them. They wanted rights over “jal, jangal and zameen” (water, forest and land). They wanted an exploitation-free society, where they could dance and enjoy freely during Santhal Sohrai; where they could resolve disputes through Vitalaha. Neither the foreign imperialists nor the native colonialists could grasp the concept of Abua Raj.

Even today, Hul continues in one form or another against exploitation, from Jharkhand to Chhattisgarh to Manipur, with the active participation of Adivasis.

References:

E.G. Man, Sonthalia and the Sonthals, Mittal Publications, New Delhi, 2003

L.S.S. O’Malley, Bengal District Gazetteers Santal Parganas. V.R. Publishing Corporation, Delhi, 1984

L. Natarajan, “The Santhal Insurrection 1855-56” in A.R. Desai (ed.), Peasant Struggle in India, University Press, Bombay, 1979.

M.P. Singa, Santal Hul (Insurrection of Santhals), 1855-56, TRI, Ranchi, 1990

Kali Kinkar Dutt, The Santal Insurrection of 1855-57, Firma KLM Private Limited, Calcutta, 2000

Kedar Prasad Meena, Adivasi Vidroh, Anugya Books, Delhi, 2018

W.W. Hunter, The Annals of Rural Bengal, Cosmo Publications, Delhi, 1975

W.G. Archer, The Hill of Flutes: Life, Love and Poetry in Tribal India (A Portrait of the Santals), Isha Books, Delhi, 2007

W.G. Archer, ‘Santal Rebellion Songs’ in Verrier Elwin (ed) ‘Man in India’, Vol 25, Ranchi (Chota Nagpur), 1945

Ranjeet Guha, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1983

W.J. Culshaw, Tribal Heritage: A Study of the Santals, Gyan Publishing House, New Delhi, 2004

C.E. Buckland, Bengal Under the Lieutenant Governors, Deev Publications, New Delhi, 1976

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)