All over the world, 1 January is celebrated as the New Year’s Day. To call a day of joy and celebration as a “black day” sounds incongruous. But it is a black day for the Ho Adivasis of Kolhan, Jharkhand. One just has to be acquainted with their history to know why.

History tells us about the Ho rebellion of 1920-21 and Kol rebellion of 1831-32. The Ho Adivasis never allowed the British to usurp their land. To subjugate the Ho Adivasis and establish their control over Singhbhum, a strategy was drawn up under the leadership of Captain Wilkinson, an agent of the British Governor General. Manki, the Pradhan of the Peedh and Muda, the Pradhan of the village, were used as pawns by the British to enslave the people. But their conspiracy failed and in many places, the British had to face guerilla attacks by the Ho people. To suppress the resistance put up by the Ho people, Captain Wilkinson launched a military campaign and the British troops entered the Kolhan area in 1837. But they could never subjugate the Ho Adivasis. They could neither capture the minds of the people nor their land.

A rebellion exploded like a volcano in Kolhan under the leadership of great warrior Poto Ho. Secret conclaves were held in the dense forests where plans for hounding the British out of the area were made and groups of fighters ready to lay down their lives were forged.

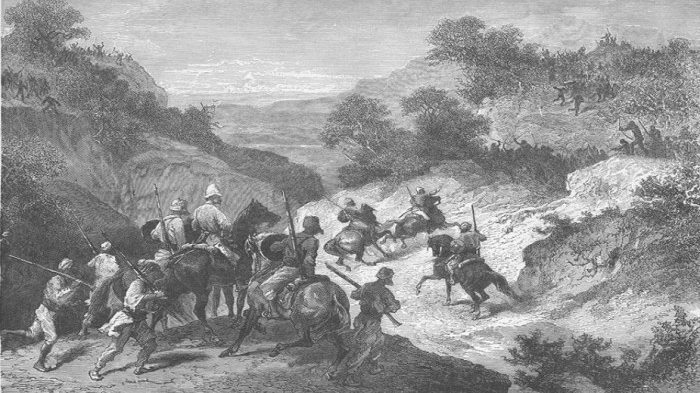

One of the places where secret conclaves were held was Pokam, a village near Jagannathpur. Besides Poto Ho, the group included Boda and Debaye of Balandia; Potel, Gopali, Pandua, Nara, Badaye of Padsa; and around 20 others. The rebellion spread to innumerable villages, including Lalgarh, Amla and Badh Peedh and took the form of a people’s movement. Mara of Balandia; Koche Pardan, Pata of Sarvil; Pandua, Joto and Jonko of Dumaria; and other valorous men joined the rebellion. To crush this urge for independence, the British burnt down many villages and women and children were brutally done to death. The only objective of the group led by Poto Ho was to protect his people from political and economic interference from outside and to force the British to flee the area. The freedom fighters managed to hold on to the strategically important Sirung Sai (Serengisa) and Bagavila valleys and waged a well-organized battle against the British. On 19 November 1837, when the British army contingent reached the Sirung Sai Valley, Poto Ho’s group, which was lying in wait, rained arrows on it. As the valley was surrounded by dense forests and hillocks on all sides, it did not take much for the Ho fighters to defeat the British. A large number of British soldiers were killed – so much so that they thought it prudent not to reveal their number. To avenge their losses, the British attacked Rajabasa village on 20 November 1837 and burnt it down. They captured Poto Ho’s father and other villagers but Poto Ho still eluded them.

Then, 300 soldiers of the Ramgarh battalion were summoned to Kolhan and the British, with the reinforcements, re-launched the campaign to capture the freedom fighters. They adopted all methods, including luring the villagers and persuading Manki Mundas to side with them. Ultimately, on 8 December 1837, Poto Ho and his comrades were arrested. Their trial began in Jagannathpur on 19 December 1837. The proceedings were completed within a week on 25 December 1837 and the verdict was pronounced on 31 December 1837. The judge was Captain Wilkinson, who was the prosecutor, too. This was clearly against all norms of justice. The British knew that until Poto Ho and his associates were alive, they would not be able to capture Kolhan. On 1 January 1838, Poto Ho, Debaye Ho and Badaye Ho were hanged to death in the presence of a huge crowd in Jagannathpur. The objective was to terrorize the people. On the morning of 2 January 1838, the rest of the rebels, including Nara Ho, Pandua Ho and Devi Ho, were executed in village Sirung Sai (Serengisa).

On 1 January 1948, a year after Independence, more than 2,000 Ho Adivasis were killed in police firing at Kharsawan Haat Bazar. They were opposing the decision to make the Kolhan area a part of Odisha. Then, on 2 January 2006, 14 Ho Adivasis were killed when henchmen of the Tatas opened fire on them. Their crime was that they were not ready to hand over their land to the Tatas.

New Year’s Day thus became a black day for the Ho Adivasis and the people of Kolhan area. No civilized society can celebrate the death of its valiant sons. That is why 1 January is observed as black day in Kolhan. No matter where they are, the Adivasis wear black badges on this day to pay tribute to their martyrs.

Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil