Democracy is characterized by complexity. It’s typically filled with a cacophony of voices, varying as they do depending on the issue that is pressing for that present moment. Even the same citizens espouse views that are internally in tension with other things they believe in, and with what they may have held to be true yesterday. Put simply, democracy implies some level of chaos. But in that richness lies its creativity and strength, or so goes the faith of prophets of democracy ranging from John Dewey to Bhimrao Ambedkar.

One can also see this democratic richness – or chaos – in the texts created by these eloquent advocates for democracy. As a scholar of Dewey’s pragmatism, I have long realized that Dewey’s “pragmatism” is a useful abstraction. His philosophy, and his philosophical commitments, change and evolve over time and myriad texts authored throughout his life. As one who has become fascinated by Ambedkar – a devoted student of Dewey’s at Columbia University from 1913-1916 – I have come to embrace the complexity that Babasaheb’s thought represents as well.

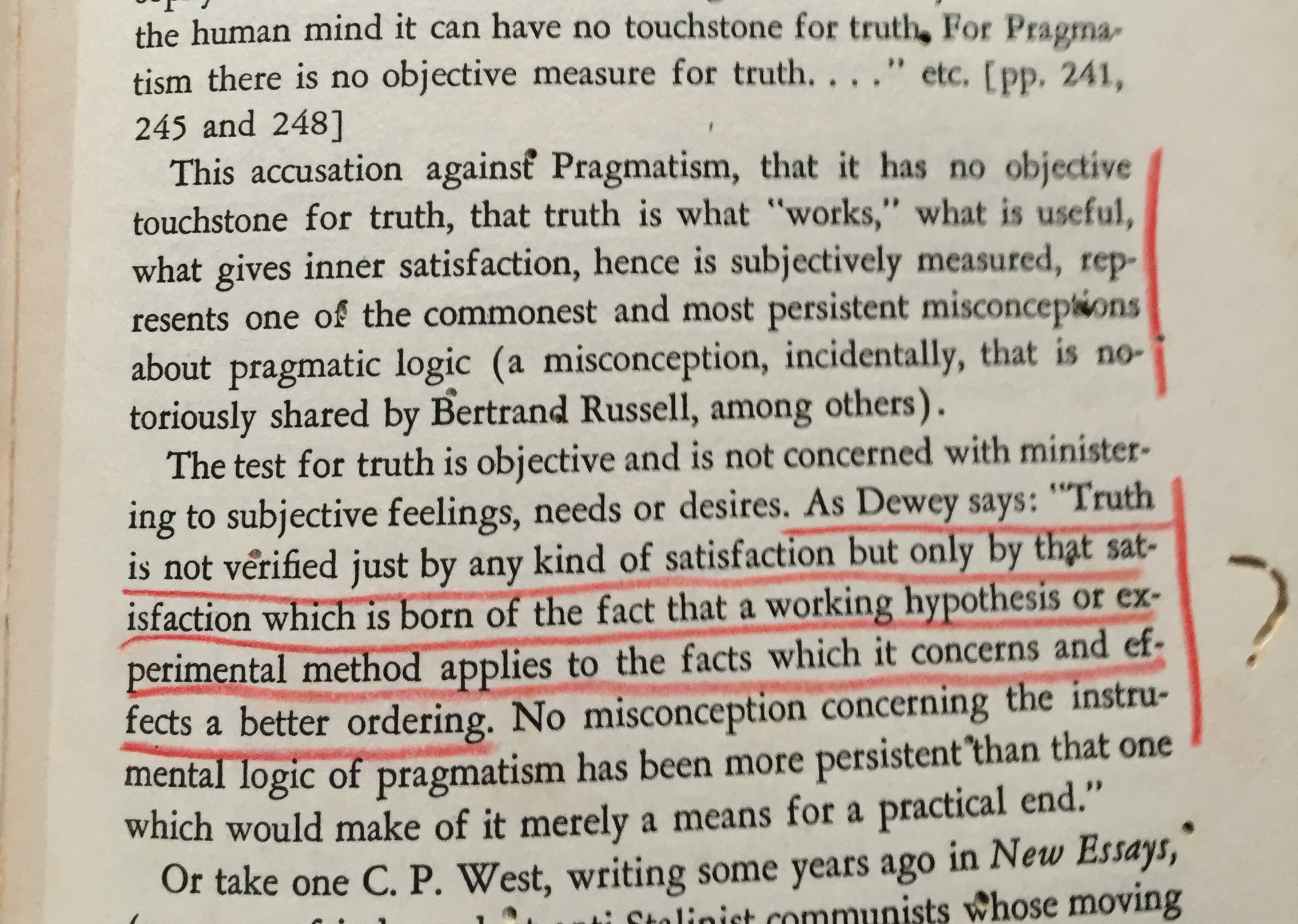

Both of these thinkers wrote and spoke so many things, many of which are directly relevant for those of us interested in social justice, ending caste oppression, and the wider challenges of walking the path of social democracy. Accessing these thinkers is deceptively easy, it seems. One can talk about “Ambedkar’s anti-caste thought” or “Dewey’s pragmatism”, but one should not think that they have grasped something certain and foundational.

Dewey’s collected works contain around eight million words, and Ambedkar’s collected English works (not counting the countless works yet to be translated from his native tongue of Marathi) hold over four million words by my estimation. Are all of these works consistent and unified in the voices that cry out from their pages? Do they never change, evolve, or mature? In a sense, these bodies of work reveal to us a chaotic democracy of texts, a symphony of rich but not always consistent perspectives clamoring for our attention.

Let us focus on Ambedkar, a vital thinker whose star continues to rise among scholars and the general public throughout the world. Simplification and selectivity are necessary to benefit from a thinker as complex as Ambedkar. One cannot present all of Ambedkar’s thought, nor would we want to, given the variable demands we face. We can read and talk about Ambedkar as an opponent of caste, or as a proponent of democracy, as an allied theorist in the fight against racism, or, as I explore in my work, a thinker creatively extending the pluralistic pragmatist tradition. There are a range of ways to think with and through Ambedkar.

One needs a way to search and select what is of value for our use in Ambedkar’s works. His different texts speak differently at different times in his life, and they speak to us in divergent ways given our ever-changing challenges of social justice and democracy. How can one intelligently construct order out of such a chaotic democracy of texts?

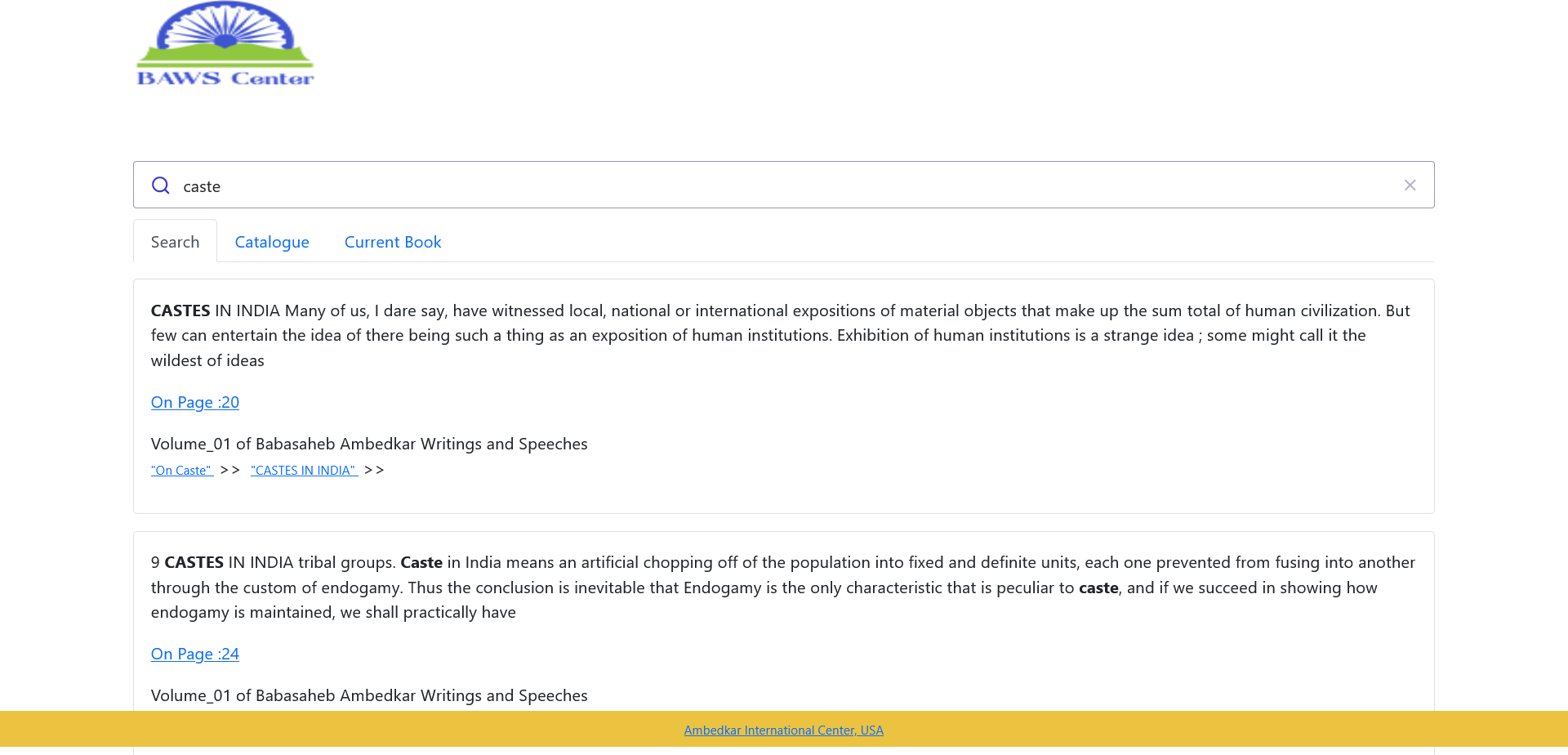

The creation of the new website, BAWS.in, represents an epochal leap forward for those of us who study Ambedkar and caste. Driven by the support and vision of Ambedkar International Center, USA, a team of volunteer programmers has turned the individual volumes of Ambedkar’s writings and speeches published by the Government of India into a fully searchable database.

Before one had to look through individual volumes to find Ambedkar’s thoughts on a specific topic. Given the complexity of his body of work, it was highly likely that one would miss a specific discussion of that topic or concern. With BAWS.in’s ever-improving abilities to search all of the volumes of Ambedkar’s writings and speeches, one can find overlooked discussions of specific topics that one didn’t know existed. The search engine’s ability to execute proximity searches (terms near other terms) is helpful for those of us looking for discussions of caste, say, near mentions of “imitation”. BAWS.in can also run synonym searches (similar but different terms from what one inputs) which enhances its power. For instance, if one searches for Ambedkar’s use of “Musalman League,” you’d also see results that contain “Muslim” and “league”. The flexibility of the search function will only increase as the BAWS.in programmers add more functions in response to user feedback, as users enter more search terms and train its algorithms, and as groups such as the Ambedkar Foundation produce higher quality scans of its volumes in other regional languages.

BAWS.in will prove invaluable to a range of users. For scholars like myself, it provides a powerful way to look for specific terms – such as “Dewey” or “Brahmanism” – and to see where they reside. Clicking on the contextual results leads you to a searchable text image of the exact page from the Government of Maharashtra edition of Ambedkar’s work. This is simply vital for scholars, since this edition and its page numbers are what we often want to cite in our scholarship.

For everyday users, BAWS.in offers a way to search out wisdom and inspiration on specific topics in the vast library of texts that Ambedkar penned or spoke. It also gives one a way to “fact-check” a phrase or quotation that one might see attributed to Babasaheb. The site allows one to dig into the context behind a specific quotation from Ambedkar; great thinkers are great because they often retain a sensitivity to nuance in their arguments, as well as the ability to utter statements with powerful brevity. Finding the full essay and speech can reveal the halo of meanings that surround a short but powerful quotation.

The team of programmers behind BAWS.in continues to seek input from scholars and everyday users as to what they would like to see in future upgrades to this service. Many more improvements are planned for the site, including proximity searches that allow one to find desired terms within a specific distance of each other and the ability of users to annotate passages of texts. The team behind BAWS.in also seeks volunteers to help with expanding the languages included in the material open to searching (right now, the site can search Ambedkar’s collected works in English; Hindi and Tamil are only readable, with search functionality coming in the future). More regional languages will become available as higher-quality scans are identified, either from the Government of India, foundations, or private users.

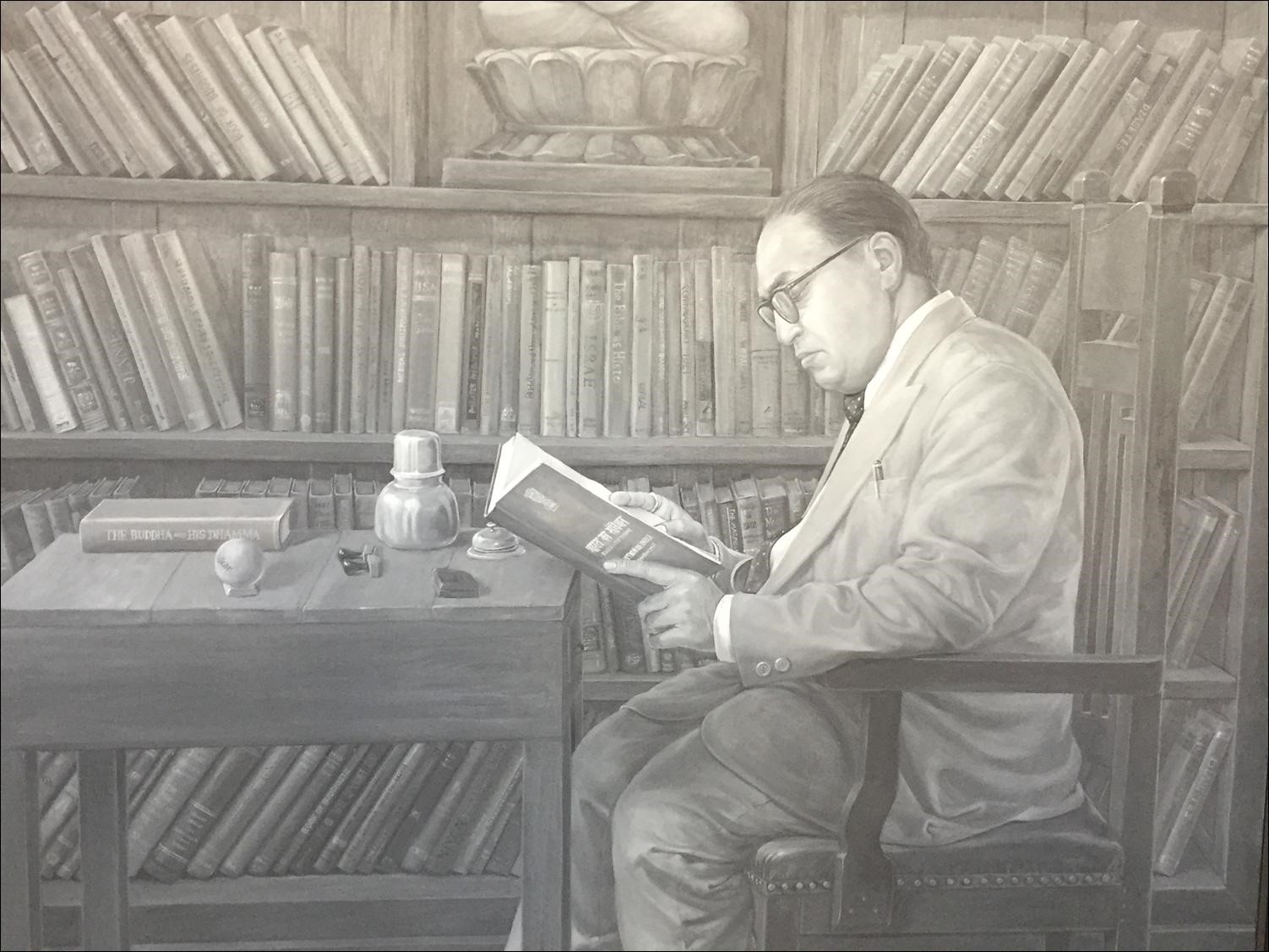

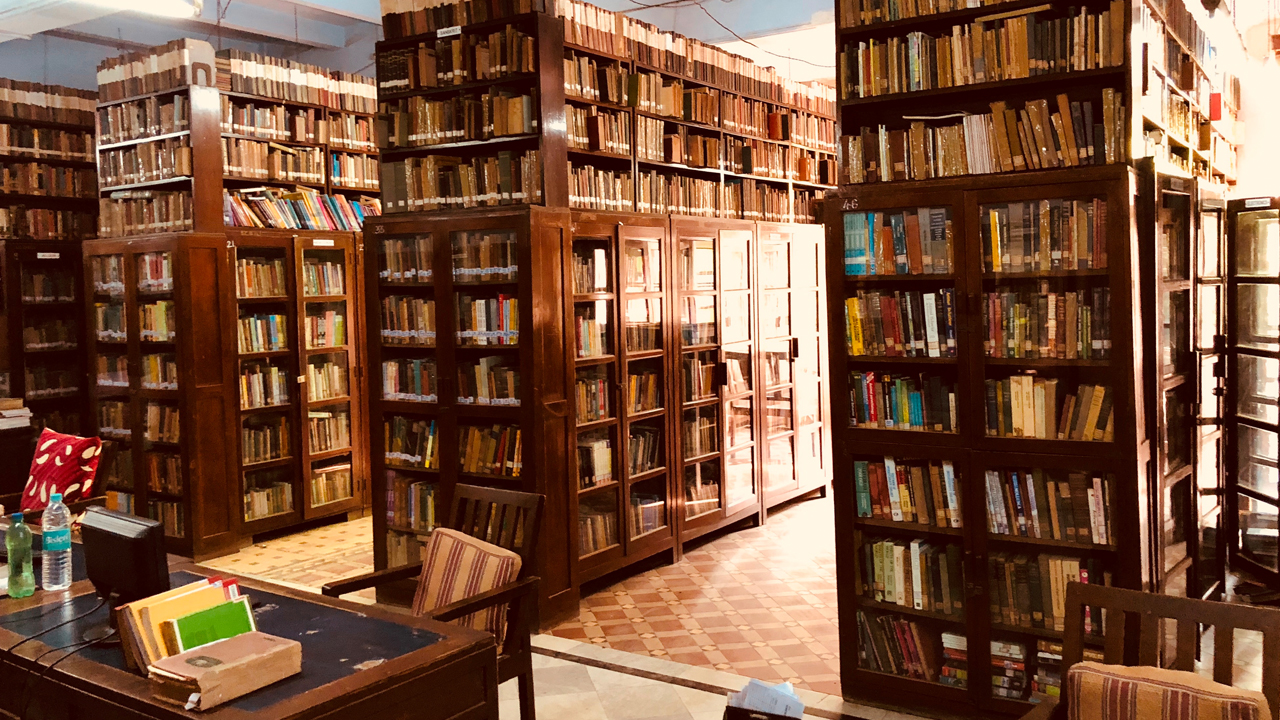

Babasaheb would love the service that the Ambedkar International Center, USA and its team has rendered to the public. He would also be thrilled that BAWS.in is completely free – comparable databases for John Dewey’s collected works, for instance, cost thousands of dollars. Only university libraries can afford them. Ambedkar wanted as many to access his thoughts, and his own books, as possible. This is why he often wrote in newspapers he founded, why he donated so much of his own personal library to his colleges, and why those following in his legacy have fought so hard to make his writings and speeches so available in the past few decades.

Ambedkar would have also loved the selectivity enabled by the BAWS.in site. He loved his books, and he loved selectively thinking through them with specific needs in mind. As Ambedkar revealed to one of his publishers in his final decades, “reading an entire book is seldom my style of reading. There are only a few books which call for deep study, from cover to cover. When I see a new title on a subject I am interested in, say socialism, I glance through the blurb, the introduction, the contents, decide which chapters would probably offer me some new thoughts and ideas on the subject. And then I read only those pages, for the rest is familiar ground. And when I have done that, you may say I have read the book” (Nanak Chand Rattu, Reminiscences and Remembrances of Dr B.R. Ambedkar, 122). Ambedkar was a busy person. What might he have been able to search out and think through if he had computerized search algorithms! Tools that enhance our purposive and pragmatic engagement with resources that our present situation demands are always welcome.

Ambedkar would surely join us in rejoicing over this new way to find novel paths through the community of texts that he has left for future generations. Please join me in thanking the programmers and supporters of this powerful new search tool for Ambedkar’s writings and speeches. Beyond thanks, however, is an even more important contribution that we make: we can use BAWS.in to learn more about Ambedkar and how we could add to his mission in our own times.

(The Hindi translation can be read here.)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)