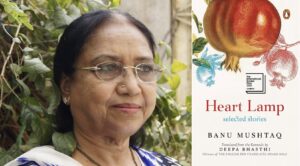

Reading 2025 International Booker Prize winner ‘Heart Lamp’ by Banu Mushtaq made me revisit my childhood memories and shudder at the latent, unconsciously practised gender disparities among which I grew up. The book is a collection of 12 short stories by the progressive social activist and author. These stories are portraits of Muslim women’s lives in Karnataka. Minus the religious affiliation, the characters contrast the developing nation they inhabit with essentialized, gendered communities.

While academic studies are the diagnoses of social problems with jargon-rich elitist language, fiction can open a layman’s eyes and nudge them towards introspection. It enables the reader to identify the prevalent injustices and violence embedded harmlessly in our moral worlds. ‘Heart Lamp’ does that, blurring the fine line that separates that author’s first-hand experience and imagination.

Written in Kannada between 1993 and 2023 and translated into English by Deepa Bhasthi, these short stories Indianize the colonial language, seasoning it with connotations from the local culture and lexicon. Pursuant to the revolutionary literary experiments of Banu Mushtaq in Kannada, the translator presents an English which is ‘Henna-fied’, ‘Talaq-ised’, and ‘Hijab-ised’. The recurring theme is that of Muslim women navigating a world of uncertainty, but each story reveals a different problematic aspect of South Indian Muslim society. The narrative technique makes for an immersive reading experience.

Women as sites of contest

All stories revolve around Muslim women and their daily experience within patriarchal society. These characters question the ubiquitous gender discrimination and power structure in Islam and among Kannadiga Muslims as the discursive element that shapes social life and customs. Instead of a sweeping portrayal of Muslim women as helpless and objectified, the author rallies defiant, formidable women characters who challenge the injustice and assert their agency. In the story ‘Black Cobra’, Zulekha Begum teaches the maid in marital distress about the rights of women in a marriage. “Why don’t scholars tell women about the rights available to them? Because they only want to restrict women”, she says.

In the stories ‘Fire Rain’ and ‘Heart Lamp’, the author laments social customs enforced on women citing religious sanctity. Women denied legal inheritance, wives deserted by wayward husbands and children in abject destitution populate Mushtaq’s stories. While men enjoy social and religious immunities, women are obliged to stay silent and conform to social demands.

Local power structure and women

The author taunts and lambasts mutawallis – the men who are in charge of local religious communities – for their utter ignorance of religion. The mutawallis are an embodiment of patriarchy and religious authority with no concern for the plight of women. Through mutawallis and others, Indian society and the Constitution allows for communal oversight over individual choices. Such a regressive social veto needs to be scrapped immediately.

Among Muslim communities, if judiciously dispensed, parallel adjudication spaces involving local leaders and aggrieved parties are more affordable and accessible than a formal court suit. But as Banu Mushtaq’s short stories depict, the same informal mechanism is highly biased against women. The women in these stories demanding honorable alimony and family support are ridiculed for the audacity to challenge male prerogatives. When Mehrun accuses her husband of liaison in the story ‘Heart Lamp’ from which the collections gets its title, her brother scornfully dismisses her, shouting, “If you had sense to uphold our family honour, you would have set yourself on fire and died. You should not have come here.”

Women’s bodies are considered as reserves of family honour and community prestige. The characters in the stories are deprived of individual choices and bodily freedom because society demands certain compliance from women. The class and caste divisions within the community make and unmake these choices.

Asifa, in ‘High-Heeled Shoe’, who is intimidated into wearing uncomfortable high-heeled shoes to match up to her expatriate sister-in-law, or Mehrun, in ‘Heart Lamp’, pushed into toxic marriage, are Banu Mushtaq’s exasperated characters, engaged in real-time conversation with the readers. The tragic fall-out of communalization of women’s honour has been a premature end to their education and denial of freedom for their personality growth, which is abundantly clear in these short stories and in everyday lives.

Do Muslim women need saviours?

What makes these short stories that revolve around Muslim women so exceptional is the conspicuous absence of both State and non-Muslim communities as prospective saviours. In contemporary India, where Muslim masculinity is vilified and terrorized using the stratagem of “oppressed Muslim women in need of saving by ‘civilized’ Hindus”, the community-initiated reform, endorsed by these short stories, deserves serious attention. How could gender inequality and attendant violence be rectified? Through laws of the State or mob vigilantism policing Muslim private lives? The story ‘Black Cobra’ gives a pertinent answer. Women have to feel that they are welcome to join religious social interactions. They have to be inducted into religious spaces, not as pious recipients, but as constructive leaders. Through pedantic provocations of characters, the author demands community-led reforms in line with changing social needs. Mushtaq also pushes for involving women in community development through recalibrating religious teachings and local power structures.

In the current political context of femo-nationalism, where Muslim women are patronized by the ruling party as being in need of liberation from “hyper-Muslim men”, these proposals for self-correction within the Muslim community are rationally more compelling. The right-wing uses the plight of Muslim women to further vilify and “other” Muslim men and shore up their support base. The supposed “rescue” of Muslims women through court and legal instruments is intended to exclude those understood to be incapable of majoritarian cultural assimilation. Given this scenario, as the Muslim conservatives look to ward off State intervention in their inviolable family lives and protect their religious freedom, self-initiated community reforms should gain support and gather momentum.

What these short stories fail to depict are the commendable strides Muslim women have made in the recent decades, especially in South India, through educational empowerment and coming into contact with foreign cultures as families migrated for work. The brave Kannadiga girl student Muskaan comes to mind. She dropped out of school after being heckled by boy students demonstrating in support of the hijab ban yet continued her education and wrote the examinations and encouraged her peers to do the same. These short stories fail to capture the world of many Muskaans out there taking on not just the patriarchy within their communities but also external hostilities from Hindu right-wing groups. Yet, the book is a must-read for its literary aesthetics and the sage insights it will evoke.