P. S. Krishnan: “One who has even a small piece of land is the king and one who doesn’t, is a slave.”

The 1990s was a decade of political turbulence in India. During that period, efforts to push the Dalits – who were trying to put themselves centre stage – back to the margins of society had begun. The decade also saw the Bahujans uniting to take on the casteists. It was in the 1990s that the government put together a committee to organize the celebrations of the birth centenary of Babasaheb Ambedkar. The person who drew the contours of the committee and the celebrations was P. S. Krishnan. He played an essential role in the constitution of the committee, which included people committed to the Dalit cause. Despite being a member of the bureaucracy, Krishnan had close ties with the common man and consistently tried to solve their problems. An IAS officer, Krishnan joined the Union Home Ministry in 1978.

I was also a member of this committee constituted by the Government of India. As far as I can remember, I first met Krishnan at the Parliament Annexe. I was there to attend the first meeting of the committee.

“Hello, Namishray ji! Congratulations on becoming a member of the committee,” he said while shaking hands with me.

After the first session of the meeting was over, we all came to the lawn for tea. Prime Minister V.P. Singh, I.K. Gujral, Rajni Kothari, Surendra Mohan, Arun Kamble, Ram Vilas Paswan and other members were also present. Among them were many of my old and new friends – these were the people who had been associated for a long time with the movement that Dr Ambedkar launched. It was an occasion for us to share our different views. Social workers, educationists, writers and journalists from all over India and MPs were present in the meeting. The meeting was presided over by V.P. Singh.

We all were committed to preserve Dr Ambedkar’s memories and take his work forward. In his brief speech, Krishnan said that along with the government machinery, there was a need to associate people with this task. Besides being a good human being and an efficient administrator, he was also a powerful orator. Till then, Krishnan knew more about me than I knew about him. I still remember him saying: “You are writing well. Keep it up.”

We could not have a long conversation at our first meeting. After the second session that followed the tea, we all headed for our homes.

About a week later, I visited Ram Vilas Paswan’s residence. Those days, I used to meet him frequently. During our meeting, he asked me about my associates. Then, tea was served. I had barely taken a sip when Krishnan arrived. I got up and greeted him. He said, “Please be seated, Namishray ji. There is no need for any formality.” He sat down beside me.

He asked me about the newspapers for which I wrote. I answered his question. I felt that he was interested in my writings on Dalit issues. At the time, Madhu Limaye’s book on Dr Ambedkar was published. He asked me whether I had seen it. I said that I had not only seen it, but also read it thoroughly. He was happy to hear this. Then, he handed me his visiting card, and he said, “Do drop in at my place some day.” I was touched by his gesture.

On a Sunday, about four to five days after our meeting, I dialled the telephone number of his residence. A servant took the call. I gave him my name, and soon Krishnan was on the line. He said, “Tell me, Namishray ji.”

I greeted him and expressed the desire to meet him. He agreed immediately and said that I should have breakfast with him. In those days, I used to live at Paharganj. Within 20 minutes, I was at the bus stand. I caught a bus and was at his place at 9 am.

At the time, he lived behind Patiala House. If I am not wrong, it was called Tilak Lane. I rang the doorbell, and someone appeared. It was the servant. I told him that I wanted to meet P.S. Krishnan. He opened the door. I entered the house and followed him inside. To the left was a big room, which looked like a drawing room. It was simple but tastefully furnished. I was asked to be seated. When I was scanning the paintings hung on the wall, Krishnan entered the room. After the exchange of greetings, he asked me whether I had faced any problems in locating his house. “No sir, I keep on visiting the Publications Division,” I said. At that time, the Publications Division was in Patiala House. Then he said aloud, “Shanta ji, come. I want to introduce you to a journalist and writer.”

Two or three minutes later, a beautiful middle-aged woman entered the room and greeted me with folded hands. I liked her humility. It impressed me. I stood up and greeted her. Then, Krishnan introduced me to her, “My wife, Shanta ji.”

Shanta ji again said namaste to me. After some time, a servant brought water and later, tea. There were some salted snacks and sweets, too. Shanta ji prepared the tea herself and passed on the cup to me. I took it and thanked her. Then, she extended first the plate of sweets and then the plate of salted snacks to me. Krishnan then said, “Shanta ji is from a Dalit community. Ours is an inter-caste marriage.”

I met Krishnan for the fourth time at the residence of the Union Social Welfare minister Sitaram Kesri, who used to ask me to drop by frequently. He had also written the foreword to my book Mansik Badhit.

Krishnan believed that one who has even a small piece of land is the king and one who doesn’t, is a slave.

Krishnan’s comment about land ownership is very significant. It is associated with the dignity of Dalits. I know it from my experience as a member of the Land Reforms Committee. Later, I also wrote a column ‘Dilli Dehat’ in Navbharat Times for two years. There is no doubt that Krishnan was committed to addressing the concerns and resolving the issues of Dalits. Later, whenever I visited their place, Krishnan and Shanta ji made me feel welcome without any formalities. On 24 February 2015, the Eshwaribai Memorial Award was conferred on Krishnan. The award, instituted by Eshwaribai Memorial Trust, was presented to him in Hyderabad by Telangana Chief Minister Chandrashekar Rao. I had met Eshwaribai in Hyderabad in the 1990s. She was a prominent Dalit social worker and worked for the Republican Party of India. Her daughter Geeta Reddy, who is the chairman of the trust, had also served as a minister in the Andhra Pradesh government.

Translation: Amrish, copy-editing: Lokesh

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

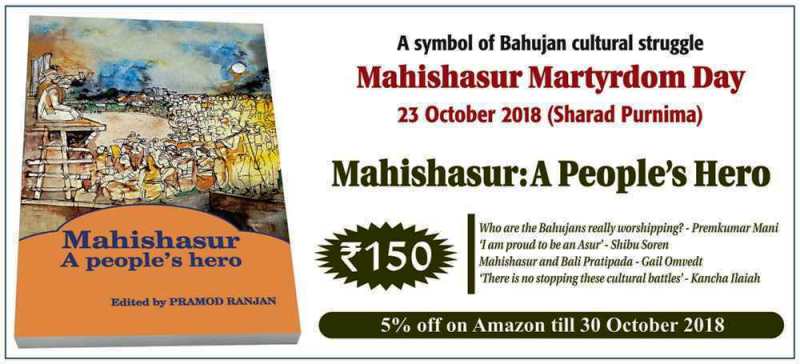

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen